The new population bomb

For the past 200 years, a rapidly rising population has consumed the earth’s resources, ruined the environment, and started wars. But humanity is about to trade one population bomb for another, and now scientists and policymakers are waking up to a new reality: The world is on the precipice of decline, and possible extinction.

For the past 200 years, a rapidly rising population has consumed the earth’s resources, ruined the environment, and started wars. But humanity is about to trade one population bomb for another, and now scientists and policymakers are waking up to a new reality: The world is on the precipice of decline, and possible extinction.

The twin forces of economic development and women’s empowerment are combining to end the age brought on by the Industrial Revolution, in which economic growth was buoyed by a growing population, and vice versa. Since the early 19th century, the rising tide of humanity has provoked many dire predictions: English economist Thomas Malthus argued as early as 1798 that population would grow so fast it would outstrip food production and lead to famine. In 1972, the Club of Rome warned that humanity would reach the “limits to growth” within 100 years, driven by a relentless rise in the global population and environmental pollution.

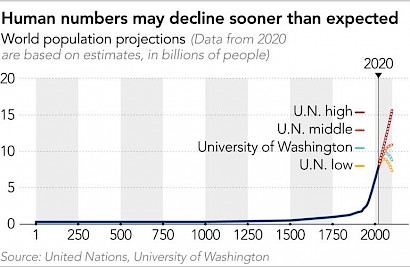

Today the world’s population, which stood as 1 billion in 1800, is now 7.8 billion, and the strain on the planet is clear. But scientists and policymakers are slowly waking up to the new numbers: The population growth rate reached a peak of 2.09% in the late 1960s, but it will fall below 1% in 2023, according to a study by the University of Washington, published last year. In 2017, the growth rate of people aged 15 to 64 – the working-age population – fell below 1%. The working-age population has already begun to drop in about a quarter of countries around the world. By 2050, 151 of the world’s 195 countries and regions will experience depopulation.

Ultimately, the study forecasts that the global population will peak at 9.7 billion in 2064 and then start declining.

Over the approximately 300,000 years of human history, cold-weather periods and epidemics have caused temporary drops in population. But now humanity will enter a period of sustained decline for the first time ever, according to Hiroshi Kito, a historical demographer and former president of the University of Shizuoka.

East Asia is one region that already faces the world’s most acute baby bust – led by South Korea’s total fertility rate of 1.11, Taiwan’s 1.15 and Japan’s 1.37 average from 2015 to 2020, according to the United Nations publication “World Population Prospects 2019.” A country’s population begins to drop when fertility falls below the so-called replacement rate of 2.1. This has led to labor shortages, pension fund crises and the obsolescence of old economic models.

East Asia is one region that already faces the world’s most acute baby bust – led by South Korea’s total fertility rate of 1.11, Taiwan’s 1.15 and Japan’s 1.37 average from 2015 to 2020, according to the United Nations publication “World Population Prospects 2019.” A country’s population begins to drop when fertility falls below the so-called replacement rate of 2.1. This has led to labor shortages, pension fund crises and the obsolescence of old economic models.

Southeast Asia, which has powered global growth as a part of the “Asian Miracle,” is also at a critical juncture. Thailand once had a total fertility rate of more than 6, but it is now 1.53, coming closer to Japan. In 2019, the working-age population began to decline, and the economic growth rate was around 2.4%. That is roughly one-third the 7.5% economic growth the country experienced in the 1970s.

Vietnam, meanwhile, became an aging society in 2017. In January the government began raising the retirement age for men and women now 60 and 55, respectively, in an effort to head off a pension crisis. It will reach 62 for men by 2028 and 60 for women by 2035.

But the biggest force behind the “degrowth” trend is China. The University of Washington predicts that its population will begin to drop from next year, and that by 2100 it will plummet to 730 million from the current 1.41 billion. By that same year, 23 countries, including Japan, will see their populations shrink to half their current levels or less, according to Christopher Murray, head of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, who has focused much of his career on improving global health.

The University of Washington study comes as a corrective to previous estimates that saw the global population continuing to grow through this century. “World Population Prospects” in 2019 estimated that the population is likely to continue to grow, reaching 10.9 billion by 2100. But new projections show the birthrate in developing countries falling faster than expected.

Murray believes global fertility will converge at around 1.5, and likely lower in some countries. “This also means that humanity will eventually disappear in the next hundreds of years,” he said.

The new reality will create new dynamics – already visible in some cases – in areas from monetary policy to pension systems to real estate prices, to the structure of capitalism as a whole. As global population approaches its peak, many governments are increasingly under pressure to rethink their policies, which have so far relied mostly on demographic expansion for their economic growth and geopolitical power.

If there are fewer workers, the growth model of the past will no longer function. Social security, such as pensions and public insurance, is premised on a growing population, and it will experience distortions.

Falling populations may solve some of the chronic environmental and social problems faced throughout the world. But new challenges await in the era of depopulation: to transform society in such a way that it does not rely on population growth. “This is a turning point for the next system of civilization,” said Kito. “It will be the difference between survival and failure.”

Scientists argue that humanity must now find a new formula for prosperity and that aggregate economic growth is no longer something that can be assumed.

Baby bust

“If we didn’t have children, we could live more freely,” said a 41-year-old manager at a major South Korean entertainment company. She has decided not to have children after discussing it with her husband when they married in 2015. Although she likes children, the cost of schooling in South Korea, a society that puts a premium on education, is climbing. Soaring real estate prices and tough employment conditions also make it more difficult to raise children. Many people around her are not even getting married, she said, adding that her sister, an elementary school teacher, has declared she will not wed.

South Korea had about 272,400 births in 2020, and its total fertility rate was only 0.84 that year, the lowest in the world. If a country’s TFR stays under 1.5 for a long time, it becomes almost impossible to raise it.

The growing ranks of educated women explain much of the variation in fertility. In Thailand, 58% of women go on to college or university, a much higher share than men, at 41%. The country’s fertility rate was 1.53 in 2020, representing a huge decline over the last few decades. According to a February 2021 report by HSBC, a bank, there is no country with a high fertility rate where the majority of women go on to higher education.

“Of course women having education and access to reproductive health is a right thing” said Murray, “It is important to think about what to do about fertility so that people don’t do wrong things.” He added that it would be a “terrible thing” were a country to think of reversing educational opportunities for women in an effort to raise fertility.

Efforts to expand social welfare systems such as day care and parental leave don’t seem to have much effect on birthrates. Finland, for example, has one of the most comprehensive social welfare systems for mothers and children in the world, yet the country’s fertility rate has declined sharply. At 1.37 in 2020, it is nearly as low as Japan’s rate of 1.34 for the same year.

“There is no definitive answer to why the fertility rate has declined over the past decade,” said Venla Berg, a research director at the Family Federation of Finland, a nongovernmental organization that provides advice on family planning policies. While currently nearly one in four people in their 20s in Finland say that they don’t want children, “there are also people who usually have less children than they wish for,” said Berg. “If people would have the number of children they want, that would bring up fertility to around 1.6 to 1.8,” she said. “This would still result in population decline, but the pace would be gradual [and] make it possible to maintain the social welfare system,” Berg added.

The coronavirus pandemic has further dented population growth. The number of births in Japan in 2020 was the lowest on record, down 3% from the previous year, while U.S. births were down 4% from the previous year, the lowest in 41 years. Many people decided not to have children because of concerns about employment and medical care. According to the Brookings Institution, a U.S. think tank, a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a 1% fall in the birthrate.

The “Japan disease”

“The U.S. and Europe are more or less following the same path as the Japanese one,” said former Bank of Japan Gov. Masaaki Shirakawa in April before a select committee in the House of Lords in the British Parliament.

He was referring to an economic and monetary phenomenon that has steadily gained attention in the U.S. and Europe, where aggressive monetary easing has not led to higher growth rates, nor ignited major price inflation. The cause may be demographic: Stagnation and deflation appeared to come with a shrinking population. When Shirakawa described Japan’s declining and aging population, some members of parliament voiced concerns about “Japanification.”

In the 1960s, Japan experienced high economic growth rates of over 10%. However, when the working-age population began to decline in the late 1990s, the growth rate slowed to the mid-1% range. It has remained low since then and nearly immune to two decades of efforts to stimulate the economy.

The same dynamics may be at work in Europe as early as next year: The population will begin to drop in 2022, according to “World Population Prospects 2019.” The European Central Bank believes inflation in 2023 will be far short of its 2% goal. According to an index by Dutch financial giant ING, the eurozone has been showing signs of Japanification since 2013.

The most overheated period for the global economy was in the early 1970s, when the global population was growing by 2% per year. Economic growth averaged about 4%, and inflation was 10% per year. This was the “golden age of welfare,” when developed countries expanded their social safety nets one after another.

But cracks are appearing in a system premised on high growth and high inflation. Global population growth has slowed to 1%, and economic growth and inflation have both slowed to between 2% and 3%. Interest rates have fallen to historic lows, casting doubts over the sustainability of pension systems.

In its 2020 report, “Shrinkanomics (the economics of a shrinking population),” the International Monetary Fund noted that a falling population can “impinge on the effectiveness of monetary policy,” citing Japan as an example. Even with low-interest rates, capital investment will not increase if companies do not expect the economy to grow.

The government can increase public investment, but this will only lead to an increase in government debt if the investments are not put to use. Continued stimulus measures probably won’t make up for the effects of a declining population, said Daniel Groh of the Center for European Policy Studies.

To overcome the Japanese disease, it is essential to invest in growth sectors to reverse shrinking demand. Digital transformation and upskilling of workers will raise productivity, while innovation is needed to meet the challenge of an aging population. Traditional economic policies need to be fundamentally rethought.

Advancement and uncertainty

“A few years ago, we would get three times more recruits than we could accept,” observed an employee with a staffing company in Vietnam that recruits workers for Japan’s Technical Intern Training Program. “These days, we can barely get twice as many. Within five years, the number of people working away from home may start to drop.”

Many Asian economies have experienced this phenomenon already, known in economics as the Lewis turning point, after British economist W. Arthur Lewis. Workers migrate from rural areas to cities, supporting economic growth by working for low wages. Eventually, growth stops because of rising wages and a shrinking labor force.

The answer, in many cases has been immigrants, which have contributed to growth in developed countries after population growth slowed. According to the U.N., there were 281 million international migrants in 2020, 1.6 times more than roughly 20 years earlier.

Border restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted how dependent some countries have become on foreign workers.

Without immigration, many advanced economies already cannot sustain their labor pool. In the U.K. after Brexit, the combination of immigration restrictions and the pandemic has led to a severe labor shortage. Before the pandemic, 12% of heavy truck drivers were from the European Union. However, drivers can no longer be hired from outside the country under the U.K.’s new standards. According to the British Road Haulage Association, the country faces a shortage of more than 100,000 commercial heavy truck drivers. Logistics companies are becoming desperate, raising hourly wages by 30%.

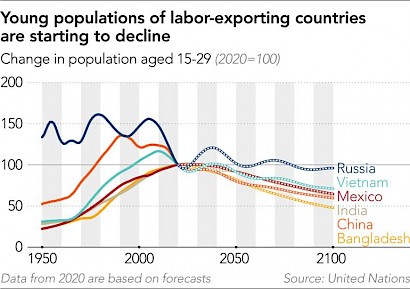

The lack of immigration may not be a temporary phenomenon. The countries with the most outbound immigrants are seeing their young populations decline. The number of Indians between the ages of 15 and 29 will peak in 2025. In China that cohort will drop by about 20% in the next 30 years.

The lack of immigration may not be a temporary phenomenon. The countries with the most outbound immigrants are seeing their young populations decline. The number of Indians between the ages of 15 and 29 will peak in 2025. In China that cohort will drop by about 20% in the next 30 years.

The Philippines, one of the biggest labor-exporting countries in the world, where about 10% of the population is thought to work abroad, is also showing signs of reversing course to focus on domestic production. The country is increasing the amount of domestic contract work, such as call centers. The incoming amount of overseas remittances grew by over 7% year-on-year in the first half of the 2010s, but that slowed to 3% in 2018.

Some countries have already started trying to secure workers. Germany increased its acceptance of non-EU workers in 2020. In 2019, Australia increased the maximum length of working holidays from two years to three, on the condition that people work for a set period of time in sectors where there is a labor shortage, such as agriculture. Japan also is bringing in more foreign workers through the “specified skilled worker” system.

Economic forces may drive a new competition among nations for immigrants. One key is to become a “country of choice.” “A policy of actively accepting immigrants means it is important to expand the options for foreign workers to settle and live in a country permanently,” said Keizo Yamawaki, a professor at Meiji University in Tokyo who specializes in immigration policy.

Getting old before getting rich

Asia’s baby boomers are reaching retirement age, and the population as a whole is growing older, and governments have experienced a rapid increase in social security spending, including for pensions and medical care.

With an over-65 population of more than 21% and a per capita gross domestic product of above $44,000, Japan has become a “super-aged society.” When the working-age population and companies can no longer support the social security system, government funding becomes the only option.

In China, the number of births skyrocketed after the Great Chinese Famine of 1959 to 1961, and the total population increased by about 190 million in the following decade. China’s baby boom generation, which is 1.5 times the size of Japan’s total population, will begin to reach the retirement age of 60 next year. The burden of this mass retirement will fall on a society of the “unwealthy elderly,” who will grow old before they become wealthy.

“It’s a hard life,” said Chen, 59, who lives in a farming village in China’s eastern Jiangsu Province. He works as a plasterer, building brick houses. Chen suffers from a chronic illness, but with no pension he does not plan on retiring when he turns 60 this year. He stayed in the village instead of moving to a city so he could take care of his parents.

China’s transition to a market economy since the 1980s sent migrant workers streaming to cities. Families in rural areas are increasingly unable to support their elderly relatives. Just over 70% of the population has joined the pension system that was set up in 2009. Its benefits are about 10% the average income of the working-age population. An insurance system for elderly care, like that of Japan, is still in the trial stage.

Reforms to make it easier for people to work, regardless of age, are also lagging in Asia.

In South Korea, about 8 million people born between 1955 and 1963 are entering retirement. The country urgently needs to raise the retirement age, currently 60, but the debate is not making progress. Raising the retirement age would make it more difficult for young people, already struggling, to find work. Young Koreans are already skeptical of the administration of President Moon Jae-in, and making the labor market more perilous could lead to an even greater backlash. Companies concerned about growing labor costs also oppose lifting the retirement age.

In Taiwan, the average retirement age is 56. Over 40% of those aged 55 to 59 are no longer working.

Many married couples in Taiwan who both work full time retire early to take responsibility for raising their grandchildren. This division of labor has long supported the economy, but the declining birthrate will disrupt this model of early retirement, too. The “Labor Insurance” system, a pension system, now faces the possibility of financial collapse in 2026.

Even developed countries that have grown rich before growing old are not immune to these challenges. The social security systems in Japan, Canada and European countries are based on the principle of intergenerational support, in which the working-age population supports retirees. With the birthrate declining, the only way to sustain pensions without increasing the burden on the public is to increase investment returns. However, a shrinking population also weakens the economy’s ability to grow, creating a vicious cycle that has spurred historic drops in interest rates.

The only way to maintain social security in an era of declining populations is to keep the economy growing by raising labor productivity. Only those countries and regions that take on these reforms will be able to ensure security in old age for their citizens.

Shifting power and shared values

Paul Morland of St Antony’s College, Oxford University, argues in his 2019 book “The Human Tide,” that many of the wars of the last two centuries were triggered by the threat of growing populations in neighboring countries. In the approach to World War I, for example, the British and French were particularly nervous about Germany’s industrial and demographic might. The Germans, meanwhile, were constantly looking at the enormous size of Russia, which was starting to industrialize very quickly, Morland writes.

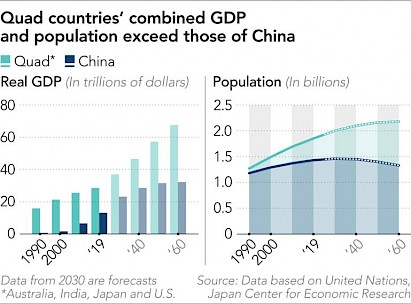

But “by itself, demography does not create power,” Morland points out. For instance, China has always been the most populous country in the world. But it was powerless before Europe and Japan in the early 20th century. “However demography is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for power. Without its great population, China would not have been able to become a great power once it roused itself organizationally and industrially.”

China, whose rise has been largely supported by its massive workforce, could face a turning point in the coming decades as its population faces a sharp drop. Beijing published its national population census in May, which showed the average annual growth rate at 0.53% over the past 10 years, the slowest pace in decades.

Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, believes China’s demographic constraints will deal a heavy blow to its economy. “China’s current GDP per capita is only 16% that of the U.S. In the future, China is facing an economic recession due to aging,” he said. “Without an increase in the number of births, the economic growth rate cannot be raised and the country can never surpass the U.S. in terms of GDP in the future,” he added.

A longtime critic of China’s one-child policy, Yi thinks that China’s population has been in decline since 2018. While the official population figure in 2020 stood at 1.41 billion, he thinks it was actually 1.28 billion, or around 130 million “surplus” people. “India’s population should already be larger than China’s,” which would make it the world’s most populous country, he said.

The authorities’ announcement of population growth comes as “they probably have judged that they would face unprecedented political upheaval if they published it in a proper way,” Yi said. In a country where the idea of having only one child is taken for granted, “the number of births will continue to decline,” he stressed.

The authorities’ announcement of population growth comes as “they probably have judged that they would face unprecedented political upheaval if they published it in a proper way,” Yi said. In a country where the idea of having only one child is taken for granted, “the number of births will continue to decline,” he stressed.

Although the Asian superpower scrapped its decades-old one-child policy in 2015, replacing it with a two-child limit, it struggles to sustain a surge in births. Beijing recently mandated a three-child limit just weeks after publishing the census.

The political agenda behind the official Chinese data is clear. Admitting that the population has suddenly dropped would mean laying bare past policy failures. Multiple research organizations estimate that China’s GDP will surpass that of the U.S. around 2030, but Yi believes that China’s population data overestimate the actual number of people by more than 100 million, thus the U.S. and China will not trade places in their GDP ranking.

The authorities have banned Yi’s book, “Big Country With an Empty Nest” in China.

In response to Western media reports that “China is facing a population crisis,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying said: “China’s population continues to grow, and is larger than that of the U.S. and Europe combined.”

China is not the only large country whose geopolitical heft is threatened by demographics. According to the U.N., Russia’s population will drop by about 20 million by 2100. Russian President Vladimir Putin has declared this to be a crisis: “Our historic duty is to respond to this challenge,” Putin said in 2020 television address.

“Russia’s fate and its historic prospects depend on how many of us there are.”

The U.S. will also enter a period of demographic decline which will have massive economic consequences. U.S. economic growth has slowed, and wealth has become more unevenly distributed, unleashing a wave of “America First” populism and nationalism.

Military power has also shifted. Rather than being a numbers game of troops, tanks, ships and planes, military power is now a contest of quality. The era when population was directly linked to military and economic power has passed.

Just as democracy and capitalism won the Cold War through the superiority of their systems, nations are now competing to construct a framework that can achieve prosperity without relying on sheer numbers of people.

The future will belong to those societies that can restructure to face decline before it is too late.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.