Brazil guts agencies, ‘sabotaging environmental protection’ in Amazon

“The Bolsonaro government has a clear policy for dismantling national environmental policies. It is delegitimizing the federal environmental bodies and its employees, sacking competent staff and appointing ill-prepared people to head departments and ‘flexibilizing’ the regulations that form an important part of environmental policies in every country. He is destroying all this,” Suely Araújo told Mongabay. She is a senior specialist in public policies at Observatório do Clima, a network of Brazilian NGOs working on climate change issues.

What the dismantling of the country’s environmental agencies and policies looks like in practice has been described in detail in a new report, published 22 January by Observatório do Clima. It maps out how the Bolsonaro government has systematically slashed the budget for environmental monitoring and firefighting — reduced by 9.8% in 2020, then by another 27.4% in 2021. The cuts are so sweeping they make it impossible for the nation’s environmental agencies to carry out their work effectively, according to the report.

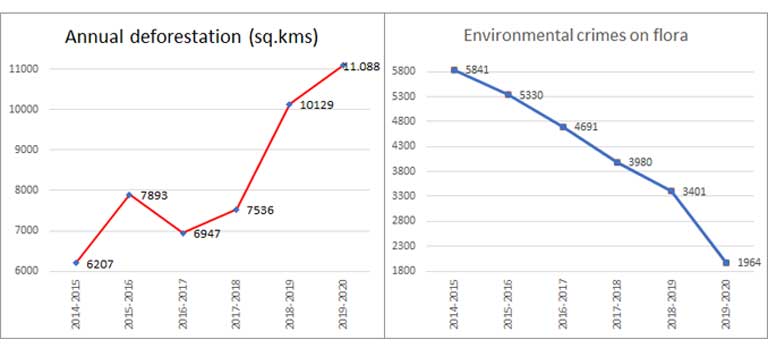

Critics point out that, if the government was truly committed to environmental protection, these cuts would make no sense at all. Another proof: even as Brazil’s deforestation soars under Bolsonaro (with an increase of 34% in the last two years) federal agencies’ capacity to punish criminals has steeply declined due to chronic funding shortages. The number of fines imposed for illegal deforestation and damage to vegetation, instead of rising with increased criminal activity, has fallen steeply by 42% from August 2019 to July 2020, according to figures supplied by the government’s environment agency, IBAMA.

A side-by-side comparison of rising annual deforestation in square kilometers and the plummeting number of forest-related environmental crimes charged in Brazil from 2014 to 2020. Image by Thais Borges / data by INPE (deforestation) and IBAMA (crimes).

Far from trying to stem deforestation, Observatório do Clima believes the government has a very different goal. “It is opting not to have environmental policies, to have paralysis,” said Araújo. “The resources going to the Ministry of the Environment and bodies linked to it are so small that reducing them won’t make much difference to the country’s account. When you cut yet further resources that are already insufficient, your goal is to mess things up. It is sabotage. We must remember that, as well as the unacceptably low 2021 budget allocation, the government has refused money from the [internationally supplied] Amazon Fund since January 2019.”

The government’s intention of dismantling environment protections isn’t only apparent in its drastic budget cuts, says the report. The administration has also pushed deregulation and rule changes rapidly, in an “infra-legal” way; that is, moving outside legal processes. Nearly 600 important regulatory changes have been implemented to date with nothing more than a presidential signature.

These key alterations include the “flexibilization” of controls over suspicious Amazon timber exports; attempts to permit oil exploration in sensitive areas, as for example when it endeavored to open up the Abrolhos archipelago, the most diverse marine region in the South Atlantic, to oil exploration; the cramming of military officers into environmental bodies; and the proposed merging of ICM-Bio (the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation which administers the nation’s protected areas), with IBAMA.

The approach to the government’s wholesale environmental deregulation, says the report, was revealed by Brazilian Environment Minister Ricardo Salles at a meeting of state government ministers on 22 April 2020, which was videotaped. The government tried to prevent the video being made public, but its release was forced by a ruling on 22 May by judge Celso de Mello, who heads the Federal Supreme Court (STF).

Using a phrase during the meeting that has since become famous across Brazil, Salles urged the state governors to take advantage of the mainstream media’s hyper-focus on the COVID-19 pandemic in order to get to work “passando a boiada” (pushing through the cattle). That’s a ranching term originally referring to the rounding up of cattle to quickly get them across a river — a phrase which Observatório do Clima used as the title to its report. Salles was explicit in his meaning: “There’s an enormous list of things we can simplify in all the ministries that have a regulatory role. We don’t need Congress,” he said.

An IBAMA agent on an illegal deforestation raid inside Jamanxim National Forest in Pará state, Brazil, previous to Jair Bolsonaro’s rise to power in January 2019. The Bolsonaro administration has largely defunded IBAMA, greatly diminishing its capacity to make such raids. Jamanxim today is seeing an extraordinary rate of illegal deforestation. Image courtesy of IBAMA.

Mongabay contacted Brazil’s Environment Ministry for a comment on the allegations made in the report. As of the time the article went to press, the ministry had not replied.

But, says the report, Bolsonaro’s policies face pushback in Congress, the judiciary and civil society. The government ended 2020 facing four high-impact lawsuits which are going before the Federal Supreme Court (STF), addressing attempts to dismantle environmental policies. Earlier, the STF imposed defeats on the administration by requiring explicit policies to better protect Indigenous peoples and force it to supply emergency help to combat COVID-19 outbreaks in Indigenous territories.

The dismantling of environmental policies has also been clearly aimed at traditional communities, including Indigenous peoples. But there are other ways in which indigenous peoples have been deliberately targeted by the Bolsonaro government.

The Observatório do Clima gives several examples: Normative Ruling no.9, issued by the indigenous agency, FUNAI, permits private landowners to claim land in Indigenous territories, provided the Indigenous land hasn’t been fully demarcated; and Draft Law 191/2020, regulates economic activities, such as mining and logging, and the construction of hydroelectric dams within Indigenous territories. Add to that Bolsonaro’s diatribes against Indigenous people in which he encourages invasions of Indigenous land, invasions which, according to the Catholic Church’s Indigenous Council CIMI, increased 135% in 2019.

International Criminal Court asked to investigate

Faced with Bolsonaro’s gutting of federal environmental agencies and protections and his anti-Indigenous policies, two Brazilian Indigenous caciques — Chief Raoni Metuktire, head of the Kayapo people, and Chief Almir Surui, leader of the Surui group — have asked the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague to investigate President Bolsonaro for “crimes against humanity.” The charges are wide-ranging, with Bolsonaro being accused of deaths, extermination of Indigenous people, forced migration, slavery, and for carrying out anti-environmental policies.

One of the caciques, Raoni Metuktire, aged about 90, said last year: “Ï have seen many presidents come and go, but none spoke so badly of Indigenous people or threatened us and the forest like this one. Since he Bolsonaro became president, he has been the worst for us.”

This is not the first time that charges have been brought against Bolsonaro at the ICC. Three attempts have been made to charge him with “crimes against humanity” because of negligence in his handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Each time the Brazilian government has refused to comment. Mongabay contacted the presidency for comment with respect to the caciques’ charges and, as of the time this article went to press, had not received a reply.

A Paris-based lawyer, William Bourdon, is acting on behalf of the Indigenous leaders in the case. He told Mongabay that the ICC has a “subsidiary jurisdiction” to that of national courts and can only get involved when the latter refuse to prosecute or are unable to. Bourdon explained: “In this case, the principle of subsidiarity jurisdiction is satisfied because the Brazilian judicial authorities refuse to prosecute and… are also unable to do so.” He said that Bolsonaro would likely be charged with “crimes against humanity perpetuated in the broader context of environment crime.” In other words, he added, if the case goes forward, Bolsonaro will likely be charged with “ecocide.”

In coming months, ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda will need to determine whether or not there are sufficient grounds for an investigation of Bolsonaro. There is no deadline for a decision, but Bourdon told Mongabay that it is a matter of great urgency. “Bolsonaro wants to destroy these Indigenous communities. We have a collective duty to protect them.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.