Biofuels look to the next generation

London, UK (by By Mark Kinver of the BBC) - Biofuels are being hailed by politicians around the globe as a salvation from the twin evils of high oil prices and climate change.

London, UK (by By Mark Kinver of the BBC) - Biofuels are being hailed by politicians around the globe as a salvation from the twin evils of high oil prices and climate change. The boom in biofuels in the US stems from President Bush’s drive to reduce dependence on imports of foreign oil; in Europe it has a more environmental dimension.

Transport is responsible for a quarter of the UK’s total emissions; four-fifths of that quarter comes from road vehicles.

Realising this could threaten to undermine efforts to meet Kyoto Protocol commitments, the UK government announced earlier this year the introduction of a Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation (RTFO).

It requires fuel companies to add 5% biofuel to all petrol and diesel sold on their forecourts by 2010.

Environmental concerns

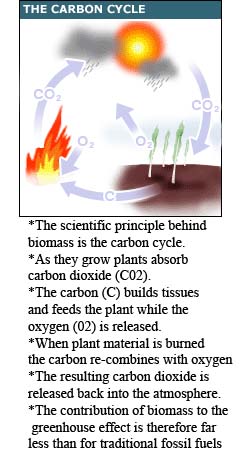

When the plant-derived biofuel is burned in an engine, the CO2 released is offset by the amount of the gas absorbed by the plants when they grew.

It is, in principle, approximately carbon neutral; though the energy needed to plant, tend, harvest, process and transport the finished product can make the equation less favourable.

The two main players in the market, bioethanol and biodiesel, are made from crops such as cereals, soybean, rape seed oil, sugar cane and palm oil.

While governments embrace what they see as a key player in a low-carbon future, there are concerns over some potential unwanted consequences.

Demand for land to grow these crops could put pressure on valuable ecosystems such as rainforests, and reduce the area available for subsistence food crops in developing countries.

Jeremy Tomkinson, chief executive of the UK National Non-Food Crop Centre (NNFCC), shares these concerns.

“If you are chopping down huge areas of rainforest in order to grow palm oil, not only is the palm oil not very environmentally friendly, think of the damage to the area’s biodiversity.

“This is a problem with some biodiesel, but the fuel we are using now is only a transitory thing.”

The next generation

Mr Tomkinson predicts that within a decade, current biofuel production methods could be replaced by “second generation” fuels.

“To me, this is the answer,” he says. “It opens up a whole new ball game.”

“What we are calling second generation, when it comes to gasoline, is the use of lignocelluloses.

Because we are going to break everything down anyway, we can look at a whole new range of crops that really are energy crops

Jeremy Tomkinson, NNFCC:”Lignocellulose is a clever, technical way of saying biomass - it means anything that comes out of the ground.”

Mr Tomkinson says it will more than double yields: “Instead of just taking the grain from wheat and grinding that down to get starch and gluten, then just taking the starch, we are going to take the whole crop - absolutely everything.”

Second generation fuel will also have a smaller carbon footprint because the amount of energy-intensive fertilisers and fungicides will remain the same, he adds, for a higher output of useable material.

Because the technology will allow biofuel to be produced from any plant material, there would be no conflict between the need for food and the need for fuel.

“We can let the lads who grow wheat grow it for nutritional value, and we can have another sector that is growing non-food crops for fuel, chemicals and pharmaceuticals,” Mr Tomkinson suggests.

“Because we are going to break everything down anyway, we can look at a whole new range of crops that really are energy crops, not short-rotation coppice crops that we are using now.”

He says two possible energy crops are sunflowers and fodder maize.

Early days

Oil giant BP is investing $500m (£266m) in an “energy bioscience institute”, which will be based in either the UK or US.

“There have been major improvements to food yields and productivity by applying plant science to agriculture,” says spokesman David Nicholas, “but it has not been done yet in terms of applying that science to the yielding of energy crops.”

BP is also investing money into research in India, where it is looking at whether it can derive biodiesel from plants that can be grown on soil not suitable for food crops.

“Biofuels are a reality and will become an increasing part of our industry, but we are at the early stages of what are the most efficient and advanced biofuels,” Mr Nicholas observes.

Second generation biofuel production is much more expensive.

There are two sizeable barriers that need to be tackled before second generation biofuels arrive at the pumps - technology and cost.

“It is technically far more complicated than current production methods,” says Mr Tomkinson. “All the different [sugars] in the plant need their own enzymes to break them down.

“A number of companies are looking at something called ‘cellulose accessing packages’ that will allow us to take a bag of enzymes and pour it on to lignocellulose and ferment the whole lot,” he explains.

The NNFCC is about to carry out a feasibility study to find out whether the UK could have a Biomass-To-Liquid (BTL) processing plant, which can produce the fuel.

Mr Tomkinson believes a BTL plant will require a serious amount of investment: “For a world-scale BTL plant, you are looking in the region of £200m ($375m).

“Currently, a 250,000-tonne biodiesel plant costs about £50m ($94m), so that is a big difference for the same amount of fuel.

But because of its environmental advantages, Mr Tomkinson says governments all over Europe are paying close attention to this technology “because BTL really could be the way forward”.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.