BC Hydro faces widespread community opposition over dam

On a warm, cloudless September afternoon in 1967, premier W.A.C. Bennett clambered into the cab of a 90-ton belly dump truck to spread the last load of fill on what was, at the time, one of the most ambitious and controversial projects undertaken in Canada.

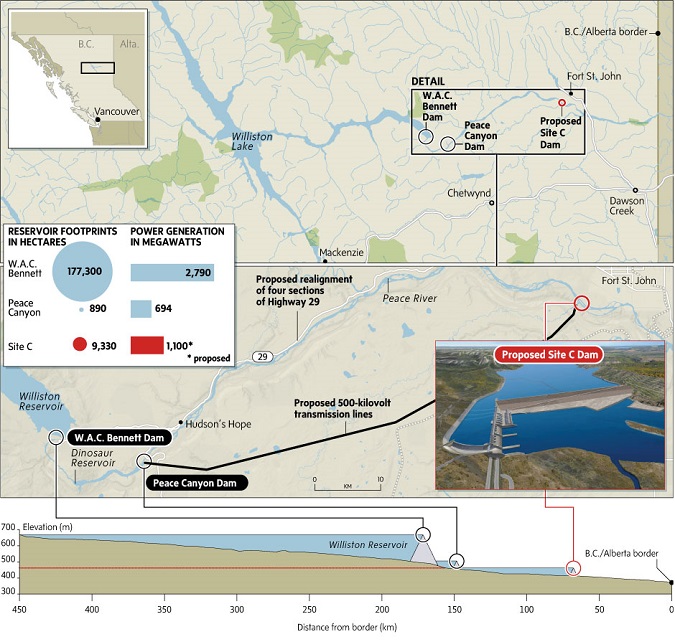

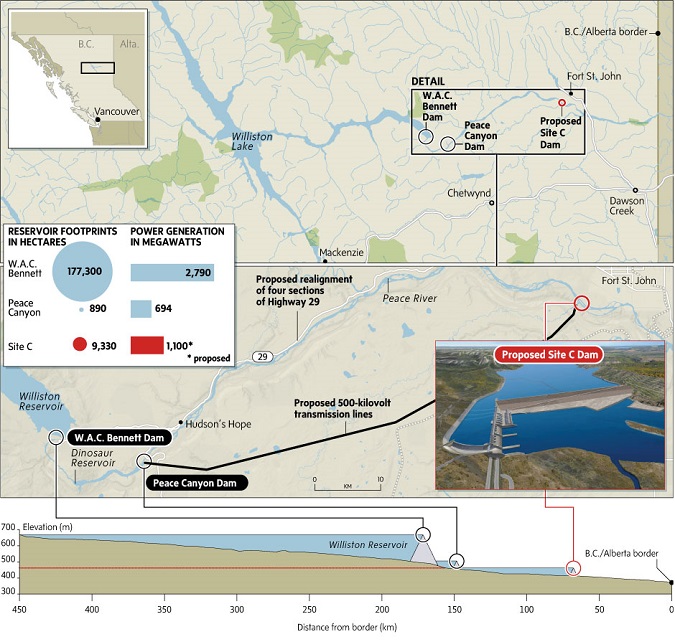

The first major dam on the Peace River would take his name in recognition of his leading role in its creation. “One man stood above all other in his faith in the future of the province,” lieutenant-governor George Pearkes intoned during the dedication ceremonies. Behind him was what news reports described as the “drab wilderness” of the soon-to-be-flooded valley in northeastern B.C.

On Dec. 9, public hearings will open in Fort St. John for an environmental review to consider another dam on the Peace River, Site C. However, this project will not proceed at full speed. Even though Premier Christy Clark wants it built and her government has exempted the project from a full public review by the B.C. Utilities Commission, Site C faces a slow path to approval.

“The days when W.A.C. Bennett could flood a valley without even logging it, without even digging up the graves in the cemetery – those days are gone,” Ms. Clark observed in a recent interview.

In addition to lengthy negotiations with regional governments and First Nations, BC Hydro has filed more than 27,000 pages of documents in preparation for the environmental-assessment process. In some cases, it has been able to dust off previous research – the $8-billion megaproject has been proposed, and rejected, twice before.

The B.C. Utilities Commission considered Site C in 1983.

At that time, the commission panel noted that the creation of the dam would cause hardship for First Nations and other residents of the valley, but this was not considered an overriding impediment. “It is simply a loss to be borne, if it can be clearly demonstrated to be in the interest of the province as a whole.”

But B.C. Hydro failed to make the case on the most fundamental and essential requirements, in the view of the regulator: It did not prove Site C was the best option to create more hydro-electricity, or that additional power was even needed.

As the Crown corporation makes one more attempt to build this dam, it faces widespread community opposition and sharp questions from the joint review panel – not only on environmental matters, but on geo-technical, economic and treaty issues.

B.C. Hydro estimates just 30 landowners will have to move or face hardship. It argues the new dam would be a source of clean, renewable energy for more than a century, producing the most cost-effective source of power, with the lowest levels of greenhouse gas emissions, compared to other power options. Hydro argues demand for electricity in the province will increase by about 40 per cent over the next 20 years and that without Site C, demand could outstrip supply.

That is little different from past arguments, but David Conroy, Hydro’s spokesman for the project, and says today’s Site C plan should not be judged on the previous proposals.

“It’s not the same project,” he said. The footprint of the massive earth-filled dam would be about the same, and the design remains an unusual “L” shape that bends to latch onto an outcropping of shale rock for stability. But it has been modernized to address concerns about earthquake safety and flood risks, and will deliver more power with bigger turbines.

The BCUC hearing in 1983 was unprecedented, but this one will be subject to even greater scrutiny. “We have never gone through like a process like this in the past,” Mr. Conroy said. “This is extremely extensive.”

Leading the opposition are the local First Nations communities.

When the Bennett dam flooded 1,800 square kilometres of the Peace River Valley, the West Moberly First Nations’ homes and graveyard disappeared into the Williston reservoir. Their traditional hunting and fishing practices were forever diminished.

Fish in the reservoir have been contaminated with methylmercury as a result of the dam. Warnings are posted regularly for residents of the region to avoid consuming more than a single serving of fish per month because the toxin can damage the central nervous system.

Clarence Wilson, a band councillor, made a horrifying discovery a little over a year ago. For generations, his family has maintained a favourite fishing spot on the Crooked River, far from where it connects to the reservoir. Every May, Mr. Wilson’s family would go there to catch Dolly Varden – until someone thought to check the trout for methylmercury. Five dozen were tested, and every one was far above acceptable levels.

“This year was the first year my family did not go to the river to camp and fish. That’s an impact from W.A.C. Bennett that nobody knows about,” Mr. Wilson said.

The Treaty 8 nations, including the West Moberly, will try at the hearing to kill Site C once and for all. But if that fails, Mr. Wilson said, they will look at other legal avenues.

“The valley is abundant in life, moose and elk and deer and all kinds of beaver, all the life in that valley, destroyed permanently so that big companies can have cheap electricity. That doesn’t make sense to us,” he said. “We don’t believe this is a project that can be reconciled with our treaty rights. It’s too much impact on an already fragile land base.”

If the dam is built, Esther and Poul Pedersen’s home will slide into the reservoir. Their hay farm and ranch in Grandhaven, just outside Fort St. John, overlooks the proposed site, but their sprawling cedar home is past the line that Hydro predicts will eventually slough into the water.

“I always wanted to live on a farm. And I have this farm. This is hard,” Ms. Pedersen said, dissolving into tears.

Ms. Pedersen was a “city girl” who decided to study agriculture. She fell in love with the valley, and landed a job as a dairy inspector before she met her husband, whose family had an extensive dairy farm. To her, this valley is not a drab wilderness, but prime farmland with a surprisingly benign micro-climate that can produce crops of corn, tomatoes and melons in the summer.

On a recent December morning with the temperature dipping to -31C, she still sees a fertile landscape. Mule deer, coyote, elk, white-tailed deer, moose and black bears have been spotted on what she calls her “little property” along the Peace River. About 50 hectares of the Pedersen’s property is expected to slough away, including the land where Ms. Pedersen built an outdoor horse arena and a shed stacked with tidy squares of hay.

So far, the couple has rejected Hydro’s offers to buy the land. Ms. Pedersen cannot bear to think of walking away. When the Williston reservoir was created, thousands of deer and elk drowned trying to cross the water to now-submerged islands. She considers the animals on her land meeting the same fate. “It’s impossible to think about.”

The first major dam on the Peace River would take his name in recognition of his leading role in its creation. “One man stood above all other in his faith in the future of the province,” lieutenant-governor George Pearkes intoned during the dedication ceremonies. Behind him was what news reports described as the “drab wilderness” of the soon-to-be-flooded valley in northeastern B.C.

On Dec. 9, public hearings will open in Fort St. John for an environmental review to consider another dam on the Peace River, Site C. However, this project will not proceed at full speed. Even though Premier Christy Clark wants it built and her government has exempted the project from a full public review by the B.C. Utilities Commission, Site C faces a slow path to approval.

“The days when W.A.C. Bennett could flood a valley without even logging it, without even digging up the graves in the cemetery – those days are gone,” Ms. Clark observed in a recent interview.

In addition to lengthy negotiations with regional governments and First Nations, BC Hydro has filed more than 27,000 pages of documents in preparation for the environmental-assessment process. In some cases, it has been able to dust off previous research – the $8-billion megaproject has been proposed, and rejected, twice before.

The B.C. Utilities Commission considered Site C in 1983.

At that time, the commission panel noted that the creation of the dam would cause hardship for First Nations and other residents of the valley, but this was not considered an overriding impediment. “It is simply a loss to be borne, if it can be clearly demonstrated to be in the interest of the province as a whole.”

But B.C. Hydro failed to make the case on the most fundamental and essential requirements, in the view of the regulator: It did not prove Site C was the best option to create more hydro-electricity, or that additional power was even needed.

As the Crown corporation makes one more attempt to build this dam, it faces widespread community opposition and sharp questions from the joint review panel – not only on environmental matters, but on geo-technical, economic and treaty issues.

B.C. Hydro estimates just 30 landowners will have to move or face hardship. It argues the new dam would be a source of clean, renewable energy for more than a century, producing the most cost-effective source of power, with the lowest levels of greenhouse gas emissions, compared to other power options. Hydro argues demand for electricity in the province will increase by about 40 per cent over the next 20 years and that without Site C, demand could outstrip supply.

That is little different from past arguments, but David Conroy, Hydro’s spokesman for the project, and says today’s Site C plan should not be judged on the previous proposals.

“It’s not the same project,” he said. The footprint of the massive earth-filled dam would be about the same, and the design remains an unusual “L” shape that bends to latch onto an outcropping of shale rock for stability. But it has been modernized to address concerns about earthquake safety and flood risks, and will deliver more power with bigger turbines.

The BCUC hearing in 1983 was unprecedented, but this one will be subject to even greater scrutiny. “We have never gone through like a process like this in the past,” Mr. Conroy said. “This is extremely extensive.”

Leading the opposition are the local First Nations communities.

When the Bennett dam flooded 1,800 square kilometres of the Peace River Valley, the West Moberly First Nations’ homes and graveyard disappeared into the Williston reservoir. Their traditional hunting and fishing practices were forever diminished.

Fish in the reservoir have been contaminated with methylmercury as a result of the dam. Warnings are posted regularly for residents of the region to avoid consuming more than a single serving of fish per month because the toxin can damage the central nervous system.

Clarence Wilson, a band councillor, made a horrifying discovery a little over a year ago. For generations, his family has maintained a favourite fishing spot on the Crooked River, far from where it connects to the reservoir. Every May, Mr. Wilson’s family would go there to catch Dolly Varden – until someone thought to check the trout for methylmercury. Five dozen were tested, and every one was far above acceptable levels.

“This year was the first year my family did not go to the river to camp and fish. That’s an impact from W.A.C. Bennett that nobody knows about,” Mr. Wilson said.

The Treaty 8 nations, including the West Moberly, will try at the hearing to kill Site C once and for all. But if that fails, Mr. Wilson said, they will look at other legal avenues.

“The valley is abundant in life, moose and elk and deer and all kinds of beaver, all the life in that valley, destroyed permanently so that big companies can have cheap electricity. That doesn’t make sense to us,” he said. “We don’t believe this is a project that can be reconciled with our treaty rights. It’s too much impact on an already fragile land base.”

If the dam is built, Esther and Poul Pedersen’s home will slide into the reservoir. Their hay farm and ranch in Grandhaven, just outside Fort St. John, overlooks the proposed site, but their sprawling cedar home is past the line that Hydro predicts will eventually slough into the water.

“I always wanted to live on a farm. And I have this farm. This is hard,” Ms. Pedersen said, dissolving into tears.

Ms. Pedersen was a “city girl” who decided to study agriculture. She fell in love with the valley, and landed a job as a dairy inspector before she met her husband, whose family had an extensive dairy farm. To her, this valley is not a drab wilderness, but prime farmland with a surprisingly benign micro-climate that can produce crops of corn, tomatoes and melons in the summer.

On a recent December morning with the temperature dipping to -31C, she still sees a fertile landscape. Mule deer, coyote, elk, white-tailed deer, moose and black bears have been spotted on what she calls her “little property” along the Peace River. About 50 hectares of the Pedersen’s property is expected to slough away, including the land where Ms. Pedersen built an outdoor horse arena and a shed stacked with tidy squares of hay.

So far, the couple has rejected Hydro’s offers to buy the land. Ms. Pedersen cannot bear to think of walking away. When the Williston reservoir was created, thousands of deer and elk drowned trying to cross the water to now-submerged islands. She considers the animals on her land meeting the same fate. “It’s impossible to think about.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.