Australia Becomes First Developed Nation to Repeal Carbon Tax

After almost a decade of heated political debate, Australia has become the world’s first developed nation to repeal carbon laws that put a price on greenhouse-gas emissions.

In a vote that could highlight the difficulty in implementing additional measures to reduce carbon emissions ahead of global climate talks next year in Paris, Australia’s Senate on Thursday voted 39-32 to repeal a politically divisive carbon emissions price that contributed to the fall from power of three Australian leaders since it was first suggested in 2007.

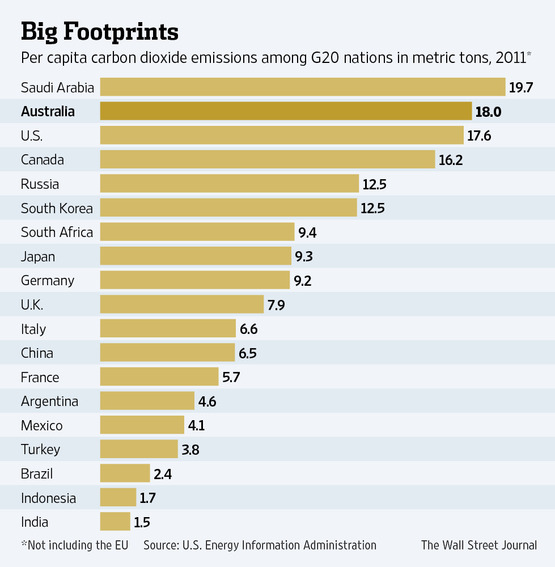

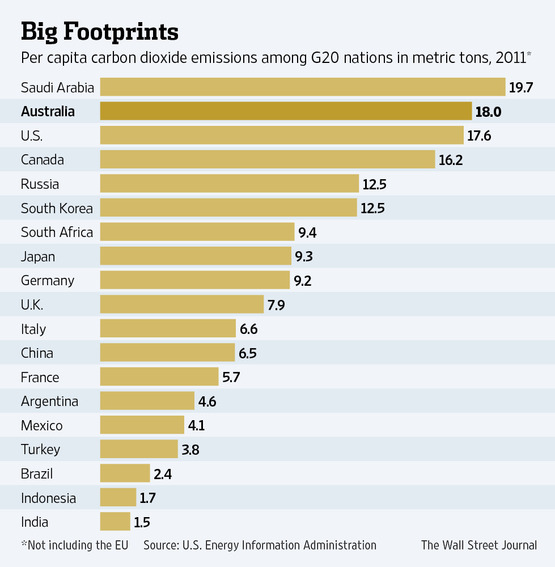

Australia, the world’s 12th largest economy, is one of the world’s largest per capita greenhouse gas emitters due to its reliance on coal-burning power stations to power homes and industry. In 2011, daily emissions per head amounted to 49.3 kilograms (108 pounds), almost four times higher than the global average of 12.8 kilograms, and slightly ahead of the U.S. figure of 48.2 kilograms.

The former Labor government, while introducing a price on carbon, said the move would help slash emissions by 160 million metric tons by 2020. It offered voters billions of dollars in compensation through tax breaks and welfare payments for increased costs stemming from one of the most dramatic reforms ever attempted in the energy-reliant economy.

But after the global financial crisis took hold in 2008, followed by the end of a decadelong mining boom in 2012 that slowed growth and employment in the A$1.5 trillion (US$1.4 trillion) economy, Australian voters turned against climate laws—recognized by the International Energy Agency as model legislation for developed countries—blaming them for rising energy bills and living costs.

The World Bank in May produced a State and Trends of Carbon Pricing report counting carbon pricing programs in 40 nations and 20 regions worth a collective US$30 billion, while also singling out repeal plans in Australia as one of the biggest international threats to the rollout of similar programs elsewhere, given its example.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who made a pre-election “pledge in blood” to voters and business to prioritize growth above climate shift, delivered on his promise after independent senators with deciding votes in the upper house sided with his conservatives, following a power shift this month that ended years of domination by the pro-environment Greens party.

“Today the tax that you voted to get rid of is finally gone, a useless destructive tax which damaged jobs, which hurt families’ cost of living and which didn’t actually help the environment is finally gone,” a jubilant Mr. Abbott told voters in a news conference after the Senate’s decision.

He said the carbon price was acting as a A$9 billion a year handbrake on the economy, which was adjusting to the end of a record mining investment boom that helped shield Australia through much of the recent global economic downturn.

Without matching emissions policies in other industrialized countries, Mr. Abbott had said earlier the tax was an unfair shackle on local companies and individuals, unequaled except in Europe, where an emissions market has operated since 2005.

Labor and Green opponents of the government said the repeal would make the country an international “pariah” on efforts to combat climate change.

“This is a fundamental moment in Australia’s history. We are about to devastate the future of this country,” said Labor Senator Lisa Singh in an impassioned speech warning the government that climate warming would impact most on future generations.

The carbon tax and plans for an eventual emissions market dominated Australian politics for years, gaining momentum in 2007, when former Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd called climate change “the greatest moral challenge of our time” and made signature of the Kyoto climate protocol one of his first political acts after winning power. Mr. Abbott defeated Mr. Rudd—then in his second stint as prime minister—10 months ago, in an election fought largely over the carbon price and its impact on energy costs.

The carbon tax has affected industries ranging from mining and energy to aviation, and was widely opposed by manufacturers and a majority of business representative groups including the country’s main chamber of commerce.

David Byers, chief executive of the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association, an industry group, said: “Today’s repeal of the carbon pricing mechanism is significant as it removes a cost facing Australian LNG (liquefied natural gas) exporters competing in global markets; one that does not exist for our international competitors.”

While BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s largest miner, said its management believed in having a price signal on carbon, the company has argued the current system wasn’t competitive internationally.

“We have been very clear that we are strong supporters of both the repeal of the carbon tax and the mining tax,” BHP Billiton Ltd. Chief Executive Andrew Mackenzie said in an interview. He said repealing the “misdesigned” carbon tax would be very important in increasing Australia’s competitiveness at a time when companies selling exports have faced challenges including a historically high Australian currency.

J.P. Morgan ,last year estimated the removal of the carbon tax, together with the repeal of the government’s mining levy, would boost its valuation on companies such as BHP and Rio Tinto PLC by as much as 6%.

Energy provider AGL Energy Ltd., said the repeal would hurt earnings in the near term because transitional payments meant to help it cope with the impact of the carbon price on some of its coal-fired plants would cease, knocking A$186 million off its earnings before interest and tax.

But in a release to Australia’s stock exchange Thursday morning, AGL said that in the long term, the repeal would have a “materially positive impact,” along with associated measures still under consideration by the government to weaken a long-standing target for 20% of Australia’s electricity needs to come from renewable sources by 2020, boosting coal-fired power.

Airline operators also said they had been hurt badly by the tax, at a time when intensifying competition in Australia’s domestic travel market was already driving down ticket prices. Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd., said it lost A$27 million in the six months through December 2013 due to the carbon tax, saying it couldn’t pass costs on to passengers because of stiff market competition. It reported a first-half loss of A$83.7 million.

Wesfarmers Ltd., Chief Executive Richard Goyder said companies would “act within their own operations to deal” with reductions in carbon emissions. Australia’s Wesfarmers runs Coles, one of the country’s biggest supermarket chains, as well as mining and chemicals operations.

“Business is very, very aware of this as an issue and individual businesses like the one I run have their own strategies in place to reduce their emissions regardless…of a carbon tax,” Mr. Goyder told reporters at the B20 Summit in Sydney.

Mr. Abbott has promised repeal will save voters and business around A$9 billion a year, although his government also risks a political backlash, having promised yearly savings to households of more than A$500, which economists and market analysts believe unlikely due to rising energy bills.

But his repeal may reverberate internationally ahead of global climate talks next year, when major economies like China, India and the U.S. will consider global greenhouse targets beyond 2030 that climate scientists say will be necessary to limit global temperature rises to two degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) above 19th century levels, even as many nations grapple with how to boost manufacturing and spur sluggish economies.

A 2009 climate meeting in Copenhagen ended in disagreement between the U.S. and China over how to deal with emissions, prompting some critics to give it the disparaging sobriquet “Brokenhagen.”

The Brookings Institution has previously described Australia as an “important laboratory and learning opportunity” for U.S. thinking about climate change and energy policy, as it was one of the first major countries outside Europe to adopt a carbon price. The country was also comparable in many ways to the U.S., with similarly energy-intensive lifestyles, industries and per capita greenhouse gas emissions.

Emissions programs are already in place in Europe and parts of the U.S. and Canada, as well as Japan and Australia’s trans-Tasman neighbor New Zealand. South Korea is expected to begin emissions trading next year, while China is proceeding with pilot schemes in seven locations. Europe’s emissions market covers 31 countries and 40% of total greenhouse gas output inside the bloc.

Britain in 2008 also committed to slashing emissions by at least 80% by 2050 when measured against 1990 levels, while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has finalized regulations that aim to deliver carbon pollution cuts of 30% from power plants by 2030 when compared with 2005 levels, giving teeth to U.S. President Barack Obama’s promise to tackle climate shift through mechanisms putting a price on carbon.

But there have been backward moves as well. Japan last year retreated on pledges to cut greenhouse emissions, blaming the shutdown of its nuclear plants in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster for a decision to release 3% more greenhouse emissions by 2020 instead of a 25% cut on 1990 levels previously promised. Closing down nuclear power forced the world’s fifth-biggest emitter to rely on fossil fuels for electricity generation.

Canada withdrew from the Kyoto protocol in 2011, with the conservative government saying the agreement would unfairly penalize its fossil fuel-reliant economy for failing to meet a promised 6% cut. Mr. Abbott, who shares the Canadian government’s conservative ideology, said during a recent visit to Ottawa and the U.S. that climate change was “not the only or even the most important problem that the world faces”.

“There is no question there is fragile trust and ambition around the world,” said John Connor, chief executive of Australia’s Climate Institute think tank. “At international climate talks last year in Warsaw Japan, Canada and Australia were standouts in going backward, and so steps like this do matter.”

In a vote that could highlight the difficulty in implementing additional measures to reduce carbon emissions ahead of global climate talks next year in Paris, Australia’s Senate on Thursday voted 39-32 to repeal a politically divisive carbon emissions price that contributed to the fall from power of three Australian leaders since it was first suggested in 2007.

Australia, the world’s 12th largest economy, is one of the world’s largest per capita greenhouse gas emitters due to its reliance on coal-burning power stations to power homes and industry. In 2011, daily emissions per head amounted to 49.3 kilograms (108 pounds), almost four times higher than the global average of 12.8 kilograms, and slightly ahead of the U.S. figure of 48.2 kilograms.

The former Labor government, while introducing a price on carbon, said the move would help slash emissions by 160 million metric tons by 2020. It offered voters billions of dollars in compensation through tax breaks and welfare payments for increased costs stemming from one of the most dramatic reforms ever attempted in the energy-reliant economy.

But after the global financial crisis took hold in 2008, followed by the end of a decadelong mining boom in 2012 that slowed growth and employment in the A$1.5 trillion (US$1.4 trillion) economy, Australian voters turned against climate laws—recognized by the International Energy Agency as model legislation for developed countries—blaming them for rising energy bills and living costs.

The World Bank in May produced a State and Trends of Carbon Pricing report counting carbon pricing programs in 40 nations and 20 regions worth a collective US$30 billion, while also singling out repeal plans in Australia as one of the biggest international threats to the rollout of similar programs elsewhere, given its example.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who made a pre-election “pledge in blood” to voters and business to prioritize growth above climate shift, delivered on his promise after independent senators with deciding votes in the upper house sided with his conservatives, following a power shift this month that ended years of domination by the pro-environment Greens party.

“Today the tax that you voted to get rid of is finally gone, a useless destructive tax which damaged jobs, which hurt families’ cost of living and which didn’t actually help the environment is finally gone,” a jubilant Mr. Abbott told voters in a news conference after the Senate’s decision.

He said the carbon price was acting as a A$9 billion a year handbrake on the economy, which was adjusting to the end of a record mining investment boom that helped shield Australia through much of the recent global economic downturn.

Without matching emissions policies in other industrialized countries, Mr. Abbott had said earlier the tax was an unfair shackle on local companies and individuals, unequaled except in Europe, where an emissions market has operated since 2005.

Labor and Green opponents of the government said the repeal would make the country an international “pariah” on efforts to combat climate change.

“This is a fundamental moment in Australia’s history. We are about to devastate the future of this country,” said Labor Senator Lisa Singh in an impassioned speech warning the government that climate warming would impact most on future generations.

The carbon tax and plans for an eventual emissions market dominated Australian politics for years, gaining momentum in 2007, when former Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd called climate change “the greatest moral challenge of our time” and made signature of the Kyoto climate protocol one of his first political acts after winning power. Mr. Abbott defeated Mr. Rudd—then in his second stint as prime minister—10 months ago, in an election fought largely over the carbon price and its impact on energy costs.

The carbon tax has affected industries ranging from mining and energy to aviation, and was widely opposed by manufacturers and a majority of business representative groups including the country’s main chamber of commerce.

David Byers, chief executive of the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association, an industry group, said: “Today’s repeal of the carbon pricing mechanism is significant as it removes a cost facing Australian LNG (liquefied natural gas) exporters competing in global markets; one that does not exist for our international competitors.”

While BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s largest miner, said its management believed in having a price signal on carbon, the company has argued the current system wasn’t competitive internationally.

“We have been very clear that we are strong supporters of both the repeal of the carbon tax and the mining tax,” BHP Billiton Ltd. Chief Executive Andrew Mackenzie said in an interview. He said repealing the “misdesigned” carbon tax would be very important in increasing Australia’s competitiveness at a time when companies selling exports have faced challenges including a historically high Australian currency.

J.P. Morgan ,last year estimated the removal of the carbon tax, together with the repeal of the government’s mining levy, would boost its valuation on companies such as BHP and Rio Tinto PLC by as much as 6%.

Energy provider AGL Energy Ltd., said the repeal would hurt earnings in the near term because transitional payments meant to help it cope with the impact of the carbon price on some of its coal-fired plants would cease, knocking A$186 million off its earnings before interest and tax.

But in a release to Australia’s stock exchange Thursday morning, AGL said that in the long term, the repeal would have a “materially positive impact,” along with associated measures still under consideration by the government to weaken a long-standing target for 20% of Australia’s electricity needs to come from renewable sources by 2020, boosting coal-fired power.

Airline operators also said they had been hurt badly by the tax, at a time when intensifying competition in Australia’s domestic travel market was already driving down ticket prices. Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd., said it lost A$27 million in the six months through December 2013 due to the carbon tax, saying it couldn’t pass costs on to passengers because of stiff market competition. It reported a first-half loss of A$83.7 million.

Wesfarmers Ltd., Chief Executive Richard Goyder said companies would “act within their own operations to deal” with reductions in carbon emissions. Australia’s Wesfarmers runs Coles, one of the country’s biggest supermarket chains, as well as mining and chemicals operations.

“Business is very, very aware of this as an issue and individual businesses like the one I run have their own strategies in place to reduce their emissions regardless…of a carbon tax,” Mr. Goyder told reporters at the B20 Summit in Sydney.

Mr. Abbott has promised repeal will save voters and business around A$9 billion a year, although his government also risks a political backlash, having promised yearly savings to households of more than A$500, which economists and market analysts believe unlikely due to rising energy bills.

But his repeal may reverberate internationally ahead of global climate talks next year, when major economies like China, India and the U.S. will consider global greenhouse targets beyond 2030 that climate scientists say will be necessary to limit global temperature rises to two degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) above 19th century levels, even as many nations grapple with how to boost manufacturing and spur sluggish economies.

A 2009 climate meeting in Copenhagen ended in disagreement between the U.S. and China over how to deal with emissions, prompting some critics to give it the disparaging sobriquet “Brokenhagen.”

The Brookings Institution has previously described Australia as an “important laboratory and learning opportunity” for U.S. thinking about climate change and energy policy, as it was one of the first major countries outside Europe to adopt a carbon price. The country was also comparable in many ways to the U.S., with similarly energy-intensive lifestyles, industries and per capita greenhouse gas emissions.

Emissions programs are already in place in Europe and parts of the U.S. and Canada, as well as Japan and Australia’s trans-Tasman neighbor New Zealand. South Korea is expected to begin emissions trading next year, while China is proceeding with pilot schemes in seven locations. Europe’s emissions market covers 31 countries and 40% of total greenhouse gas output inside the bloc.

Britain in 2008 also committed to slashing emissions by at least 80% by 2050 when measured against 1990 levels, while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has finalized regulations that aim to deliver carbon pollution cuts of 30% from power plants by 2030 when compared with 2005 levels, giving teeth to U.S. President Barack Obama’s promise to tackle climate shift through mechanisms putting a price on carbon.

But there have been backward moves as well. Japan last year retreated on pledges to cut greenhouse emissions, blaming the shutdown of its nuclear plants in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster for a decision to release 3% more greenhouse emissions by 2020 instead of a 25% cut on 1990 levels previously promised. Closing down nuclear power forced the world’s fifth-biggest emitter to rely on fossil fuels for electricity generation.

Canada withdrew from the Kyoto protocol in 2011, with the conservative government saying the agreement would unfairly penalize its fossil fuel-reliant economy for failing to meet a promised 6% cut. Mr. Abbott, who shares the Canadian government’s conservative ideology, said during a recent visit to Ottawa and the U.S. that climate change was “not the only or even the most important problem that the world faces”.

“There is no question there is fragile trust and ambition around the world,” said John Connor, chief executive of Australia’s Climate Institute think tank. “At international climate talks last year in Warsaw Japan, Canada and Australia were standouts in going backward, and so steps like this do matter.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.