As Hurricane Season Starts, U.S. Facing Heightened Risk

The 2013 Atlantic hurricane season starts Saturday, and scientists are warning that it is likely to be a doozy, with more storms than average and more major hurricanes (Category 3 intensity or stronger). Not only are forecasters calling for an unusually active season, they also say that there are signs that the U.S., which hasn’t had a major hurricane in a record seven years, may be particularly vulnerable this year due to a combination of weather and climate factors.

Although the U.S. has seen its fair share of damaging storms in recent years, including Hurricane Sandy in 2013 (which technically was not a hurricane at landfall), the last major hurricane to strike the U.S. was Hurricane Wilma in 2005.

Although the U.S. has seen its fair share of damaging storms in recent years, including Hurricane Sandy in 2013 (which technically was not a hurricane at landfall), the last major hurricane to strike the U.S. was Hurricane Wilma in 2005.

Scientists contacted by Climate Central warned that in part because of the dearth of major hurricanes, there may be a sense of “hurricane amnesia” setting in among coastal residents — a potentially hazardous combination for when the nation’s luck runs out.

Active season ahead

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the 2013 Atlantic Hurricane Season is likely to feature somewhere between 13 and 20 named storms — those with maximum sustained winds above 39 mph. Of those named storms, NOAA projects that between seven and 11 will achieve hurricane status, with sustained winds exceeding 74 mph, and that three or four will become major hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph or stronger.

The 2013 forecast compares to the long-term seasonal average of 12 named storms, six hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

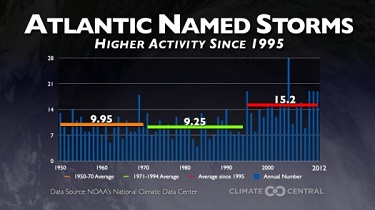

In making their seasonal outlook, which was released on May 23, NOAA cited a broad area of above-average sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic Basin, a continuation of a natural cycle of above-average hurricane activity, and a lack of an El Niño event in the Pacific Ocean as reasons why there may be more storms this year.

El Niño events can lead to stronger upper-level winds over the tropical North Atlantic, which can tear nascent storms apart before they have a chance to strengthen. Therefore, the absence of an El Niño can be like removing the brakes from a car — allowing a hurricane season to crank out more storms.

While NOAA does not issue a forecast for how many storms will make landfall in the U.S., some factors suggest that the U.S. will run a higher risk of landfalling tropical storms and hurricanes this year than in 2012. For example, just having an above-average number of storms will by itself raise the odds of a landfalling storm.

On average, the U.S. has been hit by two hurricanes per season since an active period of tropical activity began in 1995, said Gerry Bell, NOAA’s lead hurricane seasonal forecaster, in an interview. He attributed the current seven-year stretch of no major hurricanes to weather patterns that have steered such storms away from the U.S., and cautioned that it doesn’t take a major hurricane to cause severe damage, as was proven last year by Sandy.

“In a sense, yeah, we’ve been lucky, but there have been reasons for that,” Bell said.

Once they form, tropical storms and hurricanes are steered by day-to-day weather patterns. In the Atlantic, storms often form in the Caribbean or the central Atlantic and move west, around the periphery of a broad area of High pressure that typically sets up shop each summer near Bermuda — known as the “Bermuda High.”

Most storms encounter strong southwesterly winds aloft as they move northward, around the western edge of that High, causing them to turn northeast and recurve out to sea, sparing the U.S. The location of that High can be crucial for determining whether a storm hits the U.S. or not.

Some storms are able to move further to the west, into the Gulf of Mexico or near the East Coast. For example, in 2004 and 2005, the High pressure area was closer to the Southeast coast, Bell said. The air circulation around this High helped draw storms westward, and in 2004 alone, Florida was struck by four separate hurricanes.

By contrast, in 2010 and 2011, a persistent dip in the jet stream brought a stronger southwesterly flow of air at upper levels of the atmosphere along the East Coast, which helped turn many storms out to sea before reaching landfall.

Of these steering patterns, Bell said, “There’s no way to predict which of those you may have this year.” He cautioned, though, that during more active seasons the odds increase for hurricanes to make landfall in the U.S. “We know for the conditions that we expect this year, historically there is a much higher probability of multiple hurricane strikes in the U.S.”

According to James Elsner, a hurricane specialist at Florida State University, there are two key factors pointing to an above-average likelihood that the U.S. will be hit by a hurricane — possibly a major one — this season. His research has found that the lack of an El Niño event increases the likelihood of a hurricane strike, as does a climate pattern known as the North Atlantic Oscillation, or NAO.

The North Atlantic Oscillation is an atmospheric pressure pattern over the North Atlantic that can vary from one week to the next. Elsner said that if the NAO is in its so-called “negative phase” during the spring, it can often be a harbinger of greater hurricane risk in the U.S. during the following hurricane season.

The NAO’s negative phase typically favors colder and stormier weather in the eastern U.S. and Western Europe, and those regions were significantly cooler than average this spring. The U.K., for example, had its coldest spring in 50 years.

Elsner said the springtime NAO can help influence the location of the all-important High pressure area in the Atlantic Ocean, displacing it further southwest, which in turn may steer hurricanes closer to the U.S. coastline, as occurred in 2004 and 2005.

“The negative [springtime] NAO is an indicator that the U.S. will have a heightened threat this year,” Elsner said.

More people in harm’s way

With an active hurricane season looming, Bell and others warned that the continuing rapid pace of coastal development only puts more people at risk, from storm-surge flooding at the shore to inland flooding from heavy rainfall.

According to a NOAA report, the size of the population living in U.S. coastal shoreline counties jumped by 35 million between 1970 to 2010. The population of Miami-Dade County, Fla., for example, grew by 1.2 million between 1970 and 2010. With rising sea levels due to manmade climate change, storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes are already capable of doing more damage than they used to.

According to a NOAA report, the size of the population living in U.S. coastal shoreline counties jumped by 35 million between 1970 to 2010. The population of Miami-Dade County, Fla., for example, grew by 1.2 million between 1970 and 2010. With rising sea levels due to manmade climate change, storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes are already capable of doing more damage than they used to.

For example, when Hurricane Sandy pushed a record-high storm surge into New York Harbor, the surge rode on top of seas that were already about a foot higher at that location than they were in 1900, due to both climate change-related sea level rise and land subsidence.

“(For) Every storm that threatens there are so many more tens of millions of people in harm’s way,” Bell said. “Our susceptibility has increased so much due to our development, not only along the coast, but inland as well.” Bell said people need to prepare ahead of time for this hurricane season, knowing that it could be a busy one.

James Franklin, chief of forecast operations at the National Hurricane Center in Miami, said forecasters, at least, are ready for this season, having made significant improvements in hurricane-track forecasts in recent years. Hurricane intensity forecasts have lagged behind, but this season, forecasters plan to take advantage of faster, more up-to-date computer models to try to make intensity forecasts more reliable. “We think we have an opportunity to see some improvements in intensity forecasting that we haven’t seen in the last few decades,” Franklin said.

One tactic they will pursue this season, Franklin said, will be to feed live radar data from NOAA’s “hurricane hunter” research aircraft into computer models to see how that improves the intensity forecasts. Experimental work using this technique has shown some promise, he said.

Although the U.S. has seen its fair share of damaging storms in recent years, including Hurricane Sandy in 2013 (which technically was not a hurricane at landfall), the last major hurricane to strike the U.S. was Hurricane Wilma in 2005.

Although the U.S. has seen its fair share of damaging storms in recent years, including Hurricane Sandy in 2013 (which technically was not a hurricane at landfall), the last major hurricane to strike the U.S. was Hurricane Wilma in 2005.Scientists contacted by Climate Central warned that in part because of the dearth of major hurricanes, there may be a sense of “hurricane amnesia” setting in among coastal residents — a potentially hazardous combination for when the nation’s luck runs out.

Active season ahead

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the 2013 Atlantic Hurricane Season is likely to feature somewhere between 13 and 20 named storms — those with maximum sustained winds above 39 mph. Of those named storms, NOAA projects that between seven and 11 will achieve hurricane status, with sustained winds exceeding 74 mph, and that three or four will become major hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph or stronger.

The 2013 forecast compares to the long-term seasonal average of 12 named storms, six hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

In making their seasonal outlook, which was released on May 23, NOAA cited a broad area of above-average sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic Basin, a continuation of a natural cycle of above-average hurricane activity, and a lack of an El Niño event in the Pacific Ocean as reasons why there may be more storms this year.

El Niño events can lead to stronger upper-level winds over the tropical North Atlantic, which can tear nascent storms apart before they have a chance to strengthen. Therefore, the absence of an El Niño can be like removing the brakes from a car — allowing a hurricane season to crank out more storms.

While NOAA does not issue a forecast for how many storms will make landfall in the U.S., some factors suggest that the U.S. will run a higher risk of landfalling tropical storms and hurricanes this year than in 2012. For example, just having an above-average number of storms will by itself raise the odds of a landfalling storm.

On average, the U.S. has been hit by two hurricanes per season since an active period of tropical activity began in 1995, said Gerry Bell, NOAA’s lead hurricane seasonal forecaster, in an interview. He attributed the current seven-year stretch of no major hurricanes to weather patterns that have steered such storms away from the U.S., and cautioned that it doesn’t take a major hurricane to cause severe damage, as was proven last year by Sandy.

“In a sense, yeah, we’ve been lucky, but there have been reasons for that,” Bell said.

Once they form, tropical storms and hurricanes are steered by day-to-day weather patterns. In the Atlantic, storms often form in the Caribbean or the central Atlantic and move west, around the periphery of a broad area of High pressure that typically sets up shop each summer near Bermuda — known as the “Bermuda High.”

Most storms encounter strong southwesterly winds aloft as they move northward, around the western edge of that High, causing them to turn northeast and recurve out to sea, sparing the U.S. The location of that High can be crucial for determining whether a storm hits the U.S. or not.

Some storms are able to move further to the west, into the Gulf of Mexico or near the East Coast. For example, in 2004 and 2005, the High pressure area was closer to the Southeast coast, Bell said. The air circulation around this High helped draw storms westward, and in 2004 alone, Florida was struck by four separate hurricanes.

By contrast, in 2010 and 2011, a persistent dip in the jet stream brought a stronger southwesterly flow of air at upper levels of the atmosphere along the East Coast, which helped turn many storms out to sea before reaching landfall.

Of these steering patterns, Bell said, “There’s no way to predict which of those you may have this year.” He cautioned, though, that during more active seasons the odds increase for hurricanes to make landfall in the U.S. “We know for the conditions that we expect this year, historically there is a much higher probability of multiple hurricane strikes in the U.S.”

According to James Elsner, a hurricane specialist at Florida State University, there are two key factors pointing to an above-average likelihood that the U.S. will be hit by a hurricane — possibly a major one — this season. His research has found that the lack of an El Niño event increases the likelihood of a hurricane strike, as does a climate pattern known as the North Atlantic Oscillation, or NAO.

The North Atlantic Oscillation is an atmospheric pressure pattern over the North Atlantic that can vary from one week to the next. Elsner said that if the NAO is in its so-called “negative phase” during the spring, it can often be a harbinger of greater hurricane risk in the U.S. during the following hurricane season.

The NAO’s negative phase typically favors colder and stormier weather in the eastern U.S. and Western Europe, and those regions were significantly cooler than average this spring. The U.K., for example, had its coldest spring in 50 years.

Elsner said the springtime NAO can help influence the location of the all-important High pressure area in the Atlantic Ocean, displacing it further southwest, which in turn may steer hurricanes closer to the U.S. coastline, as occurred in 2004 and 2005.

“The negative [springtime] NAO is an indicator that the U.S. will have a heightened threat this year,” Elsner said.

More people in harm’s way

With an active hurricane season looming, Bell and others warned that the continuing rapid pace of coastal development only puts more people at risk, from storm-surge flooding at the shore to inland flooding from heavy rainfall.

According to a NOAA report, the size of the population living in U.S. coastal shoreline counties jumped by 35 million between 1970 to 2010. The population of Miami-Dade County, Fla., for example, grew by 1.2 million between 1970 and 2010. With rising sea levels due to manmade climate change, storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes are already capable of doing more damage than they used to.

According to a NOAA report, the size of the population living in U.S. coastal shoreline counties jumped by 35 million between 1970 to 2010. The population of Miami-Dade County, Fla., for example, grew by 1.2 million between 1970 and 2010. With rising sea levels due to manmade climate change, storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes are already capable of doing more damage than they used to.For example, when Hurricane Sandy pushed a record-high storm surge into New York Harbor, the surge rode on top of seas that were already about a foot higher at that location than they were in 1900, due to both climate change-related sea level rise and land subsidence.

“(For) Every storm that threatens there are so many more tens of millions of people in harm’s way,” Bell said. “Our susceptibility has increased so much due to our development, not only along the coast, but inland as well.” Bell said people need to prepare ahead of time for this hurricane season, knowing that it could be a busy one.

James Franklin, chief of forecast operations at the National Hurricane Center in Miami, said forecasters, at least, are ready for this season, having made significant improvements in hurricane-track forecasts in recent years. Hurricane intensity forecasts have lagged behind, but this season, forecasters plan to take advantage of faster, more up-to-date computer models to try to make intensity forecasts more reliable. “We think we have an opportunity to see some improvements in intensity forecasting that we haven’t seen in the last few decades,” Franklin said.

One tactic they will pursue this season, Franklin said, will be to feed live radar data from NOAA’s “hurricane hunter” research aircraft into computer models to see how that improves the intensity forecasts. Experimental work using this technique has shown some promise, he said.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.