America favors cars over public transit and catching COVIDiocy!

If COVID is scary as the media and Bill Gates wants you to believe — then why would anyone want to take public transit?

If COVID is scary as the media and Bill Gates wants you to believe — then why would anyone want to take public transit?

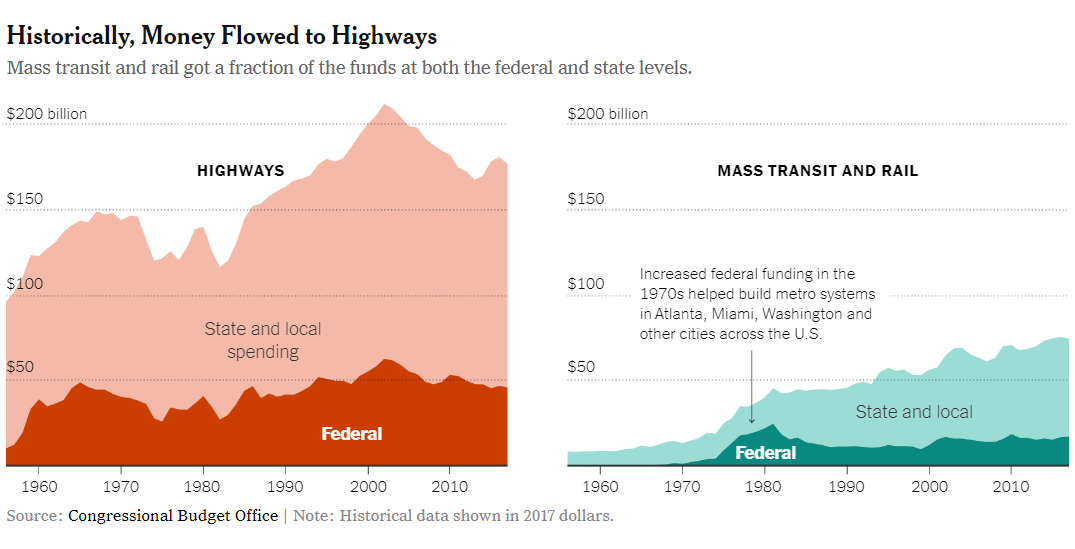

If America is dominated by car culture and the call of the open road, there is a big reason for that: Over the past 65 years, the United States has spent nearly $10 trillion in public funds on highways and roads, and just a quarter of that on subways, buses and passenger rail.

But President Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure plan, unveiled this week, represents one of the most ambitious efforts yet to challenge the centrality of the automobile in American life, by proposing to tilt federal spending far more toward public transportation and coax more people out of their cars. Experts say that transformation is necessary to tackle climate change, but could prove extremely difficult in practice.

As part of his plan, Mr. Biden wants to spend $85 billion over eight years to help cities modernize and expand their mass transit systems, in effect doubling federal spending on public transportation each year. There’s also $80 billion to upgrade and extend intercity rail networks such as Amtrak. That would be one of the largest investments in passenger trains in decades.

And, while Mr. Biden’s plan offers $115 billion for roads, the emphasis would be on fixing aging highways and bridges, rather than expanding the road network. That, too, is a shift in priorities: In recent years, states have spent roughly half of their highway money building new roads or widening existing ones, which, studies have found, often just encourages more driving and does little to alleviate congestion.

“There’s no question that the share of funding going toward transit and rail in Biden’s proposal is vastly larger than in any similar legislation we’ve seen in our lifetime,” said Yonah Freemark, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute. “It’s a dramatic shift.”

When Congress writes new multibillion-dollar transportation bills every few years, typically about four-fifths of the money goes to highways and roads, a pattern that has held since the early 1980s. To many, that disparity makes sense. After all, roughly 80 percent of trips Americans take are by car or light truck, with just 3 percent by mass transit.

But some experts say this gets the causality backward: Decades of government investment in roads and highways — starting with the creation of the interstate highway system in 1956 — have transformed most cities and suburbs into sprawling, car-centered environments where it can be dangerous to walk or bike. In addition to that, other reliable transit options are scarce.

“We’re almost forcing everyone to drive,” said Catherine Ross, an expert on transportation planning at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “The choices that individuals make are deeply shaped by the infrastructure that we have built.”

Transportation now accounts for one-third of America’s planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions, with most of that from hundreds of millions of gasoline-burning cars and S.U.V.s. And, while Mr. Biden is proposing $174 billion to promote cleaner electric vehicles, experts have said that helping Americans drive less will be crucial to meeting the administration’s climate goals.

“Far too many Americans lack access to affordable public transit, and those who do have access are often met with delays and disruptions,” Mr. Biden said on Wednesday. “We have the power to change that.”

But Mr. Biden, a longtime Amtrak rider and proponent, will face hurdles in trying to make the United States more train- and bus-friendly.

His plan still needs to get through Congress, where lawmakers in rural and suburban districts often prefer money for roads. Nationwide, new transit projects have been plagued by soaring costs. The coronavirus pandemic has also led many Americans to avoid subways and buses in favor of private vehicles, and it remains unclear when or whether transit ridership will bounce back.

The Biden administration may also have limited ability to sway the actions of state and local governments, which still account for the vast majority of transportation spending. Many key urban planning decisions — such as whether to build dense housing near light-rail stations — are made locally, and they can determine whether transit systems thrive or struggle.

“States are the emperors of transportation,” said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America, a transit advocacy group. “But so much of the culture of our current program is based on what has come out of the Department of Transportation, so it’s an important statement if the Biden administration is saying it’s time to pivot.”

Image

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.