2020 Was One of the Worst-Ever Years for Oil Write-Downs

The pandemic has triggered the largest revision to the value of the oil industry’s assets in at least a decade, as companies sour on costly projects amid the prospect of low prices for years.

The pandemic has triggered the largest revision to the value of the oil industry’s assets in at least a decade, as companies sour on costly projects amid the prospect of low prices for years.

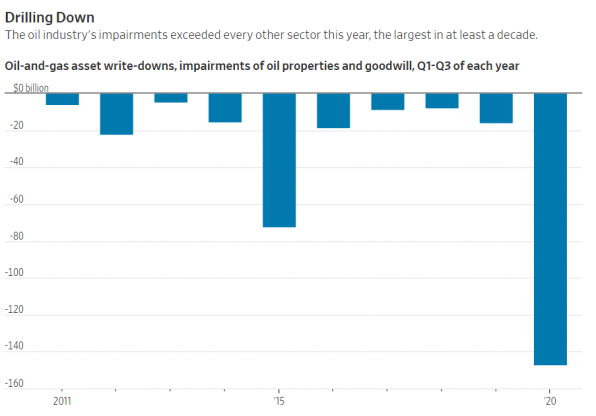

Oil-and-gas companies in North America and Europe wrote down roughly $145 billion combined in the first three quarters of 2020, the most for that nine-month period since at least 2010, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis. That total significantly surpassed write-downs taken over the same periods in 2015 and 2016, during the last oil bust, and is equivalent to roughly 10% of the companies’ collective market value.

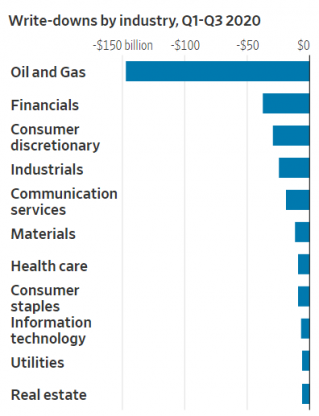

Companies across the major Western economies are writing down more of their assets during the coronavirus pandemic than they have in years. But the oil industry has written down more than any other major segment of the economy, following an unprecedented collapse in global energy demand, according to an analysis of data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Oil producers frequently write down assets when commodity prices crash, as cash flows from oil-and-gas properties diminish. This year’s industrywide reappraisal is among its starkest ever because oil companies also face longer-term uncertainty over future demand for their main products amid the rise of electric cars, the proliferation of renewable energy and growing concern about the lasting impact of climate change.

European major oil companies Royal Dutch Shell RDS.A -0.52% PLC, BP BP 2.01% PLC and Total SE TOT -0.92% were among the most aggressive cutters, accounting for more than one third of the industry’s write-downs this year. U.S. shale producers including Concho Resources Inc. and Occidental Petroleum Corp. booked more impairments than they had in the past four years combined. The data, which encompassed the first three quarters of 2020, excluded Exxon Mobil Corp.’s recently announced plan to write down up to $20 billion in the fourth quarter and the $10 billion Chevron Corp. slashed in late 2019.

The Journal’s analysis reviewed data from S&P Global Market Intelligence, Evaluate Energy Ltd. and IHS Markit on impairments taken by major oil companies and independent oil producers with a market value of more than $1 billion based in the U.S., Canada and Europe.

Regina Mayor, who leads KPMG’s energy practice, said the write-downs represent not only the diminished short-term value of the assets but many companies’ belief that oil prices may never fully recover.

“They are coming to grips with the fact that demand for the product will decline, and the write-downs are a harbinger of that,” Ms. Mayor said.

U.S. accounting rules require companies to write down an asset when its projected cash flows fall below its current book value. Though an impairment doesn’t affect a company’s actual cash flow, it can potentially raise its borrowing costs by increasing its debt load relative to its assets. Companies are also required to record impairments as earnings charges.

For the oil industry, the reassessment comes at the end of an era in which a perceived scarcity of energy supplies drove a rush to buy up fossil-fuel reserves, including U.S. shale deposits and Canadian oil sands. Some of the assets they scooped up require higher oil prices that were prevalent earlier in the decade to be profitable. But after U.S. frackers unleashed vast sums of oil and gas, there have been two oil busts in the past five years and Brent oil, the global benchmark, last topped $100 a barrel in 2014.

Concerns about long-term demand are exacerbating the oversupply of fossil fuels, and companies say they have become more selective about where they invest. Projects are facing much stiffer competition for capital amid ample supplies. BP, Shell and Chevron cited internal forecasts for lower commodity prices as the cause of the impairments.

BP believes the coronavirus pandemic could have a lasting impact on the economy, Chief Executive Bernard Looney said in June when the company announced write-downs. “We have reset our price outlook to reflect that impact and the likelihood of greater efforts to ‘build back better’ towards a Paris-consistent world,” Mr. Looney said, referring to carbon-emissions targets of the Paris climate accords.

Exxon said in November it had been strategically evaluating its assets’ profitability under current market constraints and would slash the value of some assets by a collective $17 billion to $20 billion.

The types of assets the companies are writing down run the gamut from U.S. shale-gas properties to mega-offshore projects, and intangible assets.

Shell said its write-downs mainly related to its Queensland Curtis liquefied-natural-gas project in Australia and its giant floating gas facility, Prelude, which has struggled to deliver income after years of delays and cost overruns. The pandemic has triggered a restructuring at the company, in part to refocus on the highest-value oil it produces, while also accelerating investments in low-carbon energy.

Last week, Shell signaled another write-down of between $3.5 billion and $4.5 billion, partly against its deep-water oil-and-gas project Appomattox in the Gulf of Mexico.

In coming years, heightened competition from renewable energy and policy changes toward fossil fuels could trigger further reviews of oil-and-gas assets’ ability to generate future cash flows under U.S. accounting rules, said Philip Keejae Hong, an accounting professor at Central Michigan University. Fast-growing renewable energy, he said, could chip away at the industry’s asset values over time.

“It’s not like one company is making a bad move,” Mr. Hong said. “It’s a threat that the industry as a whole is facing in the long run.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.