Net-zero living: How your day will look in a carbon-neutral world

FEW of us have fully digested the transformation of economies and our own behaviour that is implied by the existential fight against climate change – even as last month’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) laid bare how little time we have left to accelerate the transition to a cleaner world.

FEW of us have fully digested the transformation of economies and our own behaviour that is implied by the existential fight against climate change – even as last month’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) laid bare how little time we have left to accelerate the transition to a cleaner world.

It isn’t that the world is lacking in commitments. If you live in the UK, EU, US or scores of other places, the declared aim is that you should be living somewhere with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions within three decades. Eleven nations – Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden and the UK – have already written this goal into law, and dozens more have signalled their intent to do so.

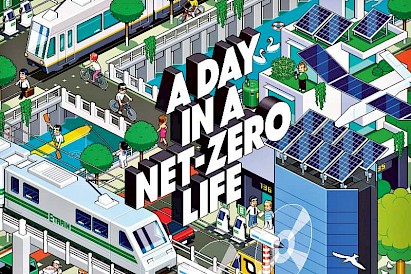

But most of us are lacking a visualisation of what daily life will be like at net zero, from our homes and food to travel and the landscapes around us. “I think we probably don’t do that enough. It’s a really helpful thing to do, to take away the fear and get people excited,” says Mike Thompson at the Climate Change Committee (CCC), a statutory adviser to the UK government.

What follows is an attempt to fill in that gap and show you a day in the life of Isla, a child today, in 2050. By its nature, it is speculative – but it is informed by research, expert opinion and trials happening right now.

TODAY IN 2050

When the alarm goes off, the torrential rain outside is almost enough to send Isla back under her duvet. That’s unusual for a late summer day. Drier and much hotter summers have been the norm for years here in the south of the UK. Mind you, unpredictable weather has become a feature of life in recent years.

Fortunately, Isla’s home is the same steady 20°C all day long, comfortable and draught-free. The idea of a home where the temperature fluctuates constantly, like her parents used to have, is alien to her. She doesn’t even know what the temperature is. An algorithm learned the warmth she prefers. Walking downstairs, Isla glimpses the unit in her garden that extracts heat from the air. Apart from some relatives in Yorkshire who still have hydrogen boilers from a big trial back in the 2020s, everyone she knows has a heat pump like this.

Making a cup of tea, Isla’s kettle looks the same as the ones her mother used three decades ago. But 95 per cent of the electricity it uses comes from wind and solar farms, a far cry from 40 per cent in 2020. The milk in her tea came from a cow. She knows that is old-fashioned, but still seeks it out in the boutique section of her online supermarket, despite the ubiquity of plant-based milk.

Today is a rare in-person day at the office. Unusually, Isla owns rather than shares an electric car – it is one of the reasons she never bothered getting a separate home battery. Charging it overnight when there is a glut of wind power sees prices flip, so firms pay to use it. Her battery stopped charging a few minutes ago, so it is warm and at its most efficient.

Driving out of town, she passes rows and rows of houses and offices with green roofs. They soon give way to a former industrial estate, now rows of boxes that look a little like jet engines, fans whirring away. They are machines to capture carbon dioxide directly from the air, fitted a few years ago by a big CO2 removal firm, Shell.

A brief journey up the motorway sees her whizzing past the lorry lane with its tram-style power cables that run above the trucks. There are more power pylons running alongside the road than when she was a child.

Back-to-back meetings at the office are followed by lunch out. Walking to a restaurant, she passes through the greenery of the Old Car Park, the wooded enclave that the local council deliberately allows to flood in winter. Isla and her dining companion both choose a burger. Not from an animal, obviously. Beef is on the menu as a high-end rarity with lots of words expended to explain its husbandry and genetic editing to curb methane emissions. It is too expensive for this casual lunch. A plant-based burger is cheaper, and does just fine.

Sleepy afterwards, Isla takes a half-day and heads home for a walk to wake herself up. The first growth phase of the Great Southern Forest seems to go on forever these days, and it is a welcome refuge from the mid-afternoon heat fast evaporating the morning’s rain. Emerging from the wood, she walks uphill through the looming elephant grass that will soon be harvested to make fuel for planes flying overhead. From the highest point, she can see a handful of cattle and sheep. She finds it hard to imagine that these rolling hills were once covered with them.

Later on, her home is still cool. Like most of her neighbours, she has no air conditioning, instead having automatic shutters for her windows, a big awning for shade and a natural ventilation system. That evening, she calls her friends. One sits chatting with the sea behind her, the 236-metre-tall blades of the Hornsea Three wind farm just about visible. Another friend in London bemoans the second days above 38°C they have had this year.

Winding down later, Isla plans a holiday. She skims past the long-haul flights, which some of her friends still take despite the rising cost of mandatory CO2 removal and the moral opprobrium that flying attracts. Happily, as she scrolls on her phone before bed, she finds the perfect option to dream about: a luxury train tour of Norwegian vineyards.

Where do the changes to Isla’s life in 2050 come from, and how likely are they to come to pass? Read on for the background in six crucial areas of our everyday lives – based on the situation in the UK, but with lessons for elsewhere in the world too (see “The global net-zero view”).

BACK TO THE HOMES

Homes in 2050 will look similar to today’s, but will feel and run differently behind the scenes. Energy efficiency and insulation will be much improved, even for older homes. Everything that can be electrified will be. Offshore wind farms including Hornsea Three, approved in December 2020 and capable of powering 2 million homes, will be the backbone of a 95 per cent low-carbon grid.

In the UK, more than four-fifths of homes are heated with gas boilers today. By 2050, they will probably be kept warm with a heat pump, effectively a reverse refrigerator that extracts heat from the air or ground to warm a fluid that is compressed to raise the temperature even higher. “It’s the most common scenario in our research,” says Thompson.

About 30,000 are being installed a year today – versus more than a million gas boilers annually – but the UK government is planning a “heat and buildings strategy”, due out this month, to meet a target of 600,000 a year by 2028. Falling costs as more installers enter the market should help. New homes and homes off the gas grid will spearhead the take-up. Meanwhile, a trial of a hydrogen-powered village is planned to take place by 2025, with a town possibly following by 2030.

Gas hobs for cooking will have made way for electric induction hobs. Combustion may not be entirely a thing of the past – the odd home may still burn wood if it hasn’t been banned because of growing concerns about particulate pollution.

Opinions differ on how engaged or not we will be with our energy use. “I think we will be more conscious energy consumers. Isla might well be thinking more about the energy she uses that day,” says Alice Bell at the non-profit organisation Possible. “They might check the weather so that if it’s sunny they know they have a cheaper energy tariff and set the washing machine and other devices.” By contrast, Thompson suspects energy won’t be something that Isla worries about, with smart systems and algorithms governing much of our home energy use, such as software being used in the Living Lab, a smart home testing environment developed by the UK Energy Systems Catapult.

One possible change is more homes needing air conditioning, says Bob Ward at the London School of Economics. Thompson hopes that doesn’t happen, less because of the extra energy – demand is low in summer and solar power output is high – but because of the heat that air-con units generate. He thinks natural shading measures and ventilation will be enough for most homes.

FOOD AND WASTE

What we eat will have changed, with a big shift towards plant-based diets, but probably not to the level of the all-vegan, meat-mocking world depicted in Carnage, a satirical film by comedian Simon Amstell. “I don’t think we will be a nation of vegans,” says Rebecca Willis at Lancaster University. The CCC’s central scenario envisages a world in which all meat and dairy consumption is down by 35 per cent. It sees that as an acceleration of current trends: meat consumption per person fell by 6 per cent between 2000 and 2018 in the UK. A more extreme scenario sees a 50 per cent fall as possible.

Mark Maslin at University College London thinks dietary shifts will be driven more by health than climate concerns. In a chapter on a 2050 “Ecotopia” in his book How to Save Our Planet, he writes: “Pandemics of the early 21st century helped shift global diets to be much more vegetable-based, helping to improve everyone’s health.”

Ward agrees, and says obesity emerging as a risk factor for covid-19 will be another push towards more fruit and vegetables in our diets. Most “meat” will probably be fake, of the plant-based kind popularised by Impossible Food and Beyond Meat, says Bell. Real meat and lab-grown meat will be more premium and niche options, she thinks. That could be driven by carbon taxes, something the UK government is reportedly considering.

“There will be a big shift towards plant-based diets, but it won’t be a vegan world”

The amount of waste that Isla produces at home in 2050 should be down by nearly half from today, according to the CCC. How that happens remains to be seen. It might mean better packaging in the first place, more reusable packaging such as that offered now by US company Loop in a handful of countries, or more boxes to sort recycling into. “We will need better systems for separation and collection,” says Thompson.

TRANSPORT

Greater adoption of hybrid or remote working will probably have curtailed some commuting in many parts of the world, with the current pandemic just one driving factor. But travelling is likely to look familiar, just with most cars and vans running on electricity or another “energy carrier” such as hydrogen, rather than oil.

The need to give more space over to cycle lanes and green spaces for carbon capture and biodiversity means there should be fewer cars, says Bell. More of those will be shared, via some evolution of today’s car clubs and ride-hailing services such as Uber. The bus taking Isla’s children to school will probably be battery-electric too, says Thompson. Heavy-duty trucks could use tram-style overhead lines to recharge; small pilot schemes are already in place in Sweden and Germany. Altogether, writes Maslin in his book, this means that in 2050 “the air is cleaner than it’s been since before the Industrial Revolution”.

Cars will be charged when there is the least pressure on electricity grids, such as overnight. They will feed back to the grid too, acting as an aggregated mega-battery that can supply the grid as needed to smooth out the variable nature of wind and solar power. Hayden Wood at UK green energy firm Bulb says he is “absolutely convinced” such vehicle-to-grid technology, which currently exists only in pilot form, will scale up. “It makes no sense to have gigawatts of battery capacity in people’s cars [that is] not being used to help balance the grid,” he says.

Electrification won’t be confined to cars. Trains are more likely to be electric, replacing the last diesel ones today, with low-use lines perhaps using hydrogen, says Thompson. Bell even envisages solar panels lining tracks and running green electricity direct to the rails, owned by the commuters on those trains, similar to today’s “Riding Sunbeams” trial in the south of England.

Trains will have to replace many shorter plane journeys, but flying isn’t going away: the CCC expects flights to increase by mid-century after a brief downward blip through and after the covid-19 pandemic. Aviation and farming will probably be the UK’s two biggest sectors still releasing greenhouse gases by 2050.

The CCC’s best estimate is that 17 per cent of planes would run on biofuels and 8 per cent on synthetic jet fuel, with the rest coming from oil. If Isla books a flight, there won’t be a box to tick for carbon offsets because all flights will be offset through some form of carbon removal, such as the direct CO2 air capture units on the outskirts of Isla’s town. The CO2 removal and alternative fuel could add around £14 to the cost of a 2050 London to New York flight, after factoring in fuel savings from more efficient planes, the CCC estimates.

LAND USE

Gazing down from those planes, the landscape should appear drastically different. “I can’t imagine the countryside will look as it does now,” says Willis. “There will be a lot more tree cover, all over the country. And a lot of mixed agriculture, not the big, flat, green fields we see at the moment.” To remove and store CO2, peatland and forests need to be restored. The CCC envisages shifts towards plant-based diets freeing up around a fifth of farmland for other uses, such as tree-planting. Energy and food production will coexist on some land; Willis’s colleagues at Lancaster University predict more solar panels in fields for the few sheep left grazing.

When it comes to ways of removing CO2, says Thompson, “we think the tree is the cheapest and most efficient way of doing this”. The CCC expects forest cover to increase from 13 per cent of UK land now to around 18 per cent by 2050, with a mix of conifers and deciduous species. “The great forests of the past will be returned gradually across the country,” says Ward. There will be more energy crops too, such as Miscanthus grasses. More land could be freed up for rewilding and reintroducing species such as beavers, thinks Maslin. The landscape is unlikely to be carpeted in fans extracting CO2 from the air. The higher costs mean such machines will only cover about 10 square kilometres compared with 10,000 square kilometres of extra forest, says Thompson.

Not all the changes to the landscape will be considered positive. There is a consensus among the CCC and other bodies including the UK National Grid that there will be a big increase in electricity generation, so as to cope with everything from heat to transport being electrified. Unless energy production becomes incredibly decentralised, with far more buildings having solar power, Willis says there will be more transmission infrastructure, such as pylons and substations, to take supplies from North Sea wind farms to homes and factories.

WEATHER

While there are many things we can’t say for certain about life in 2050, some things about the lives of Isla and her peers are clear. Most obviously, they will live in a warmer world, even if society does succeed in making the shift to a net-zero economy.

Today’s 1.1°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels will probably already be around 1.5°C by mid-century, a global average that will mask bigger jumps in places such as the Arctic. In the UK, flooding from torrential rainfall is expected to be the biggest climate impact. Extreme temperatures could be a hazard too: the UK Met Office says the possibility of 40°C days will be 10 times more likely later this century than it would be without anthropogenic climate change. “There will be more extreme weather in this country and elsewhere. Isla will be much more used to a conversation about climate impacts,” says Willis.

“The great forests of the past will return gradually across the UK”

The hope is that society will have adapted to more volatile weather. In cities, green roofs and more green spaces will both be far more common, partly to lock up CO2 but critically to offset the urban heat island effect that makes cities hotter than the surrounding area, says Maslin. In recent years, the UK government has also allocated more funding for natural solutions to flooding, such as deliberately allowing green spaces like Isla’s park to flood.

SOCIETY

Many changes we will see between now and 2050 won’t be connected with climate change – think of the jump from a pre-internet life 30 years ago to today’s hyperconnected society. Even the shifts to hit net zero are unlikely to change some fundamentals. “We’re not suddenly going back to the Stone Age”, says Maslin. “Saving the planet just makes everybody’s lives better, but we’re not going to radically change that we get born, get looked after by modern medicine, we go to school, we go to work and then we try to live as long as possible.”

One possibility is that the engagement with the public required to introduce technology and behaviour changes for net zero – akin to the 2020 citizens’ Climate Assembly UK – could invigorate democracy at a local level. “It would be lovely to think of a utopia where greening and saving the planet makes people more engaged with local politics,” says Maslin. Maybe that will happen, he says, but “I’m a bit more cynical”.

One thing is clear: with the world warming rapidly, sticking with the status quo isn’t an option. As Bell says: “Change is coming. It’s either coming from changes we make as society or it’s going to come from the skies or the soil.”

THE GLOBAL NET-ZERO VIEW

Some of the things in Isla’s life in the UK will be replicated in other nations, regardless of their income levels. The decarbonisation of electricity grids through wind and solar power and the electrification of vehicles are both seen as vital for many countries, including China. The US is among other nations looking to heat pumps.

In regions close to the equator, there will be a greater focus on innovations in cooling. That is why a test lab to create the homes of the future, Energy House 2.0 in Salford, UK, will be able to simulate different global climates.

Dietary changes will play out differently around the world. In places such as China, meat consumption is still rising. In his recent book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Bill Gates writes that cultural reasons mean stark diet shifts in some countries may be unrealistic.

One simple difference will be when the Islas of other nations might experience this life: China’s target, for example, is carbon neutrality by 2060, not 2050. India hasn’t set a long-term date for net zero yet, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi noting on 22 April that the average person in India has a 60 per cent smaller carbon footprint than the global mean.

A warmer world with more extreme weather could put more stress on some governments. “A climate strategy requires a very active role by government. I would worry in some countries, you will see political breakdown as a result. It could also result in democratic renewal in other countries,” says Rebecca Willis at Lancaster University.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.