The murky future of U.S. shale gas

“U.S. gas production appears to have hit a production ceiling, and is actually declining in major areas.”

“U.S. gas production appears to have hit a production ceiling, and is actually declining in major areas.”It was greeted with jeers. The hate mail flowed in. “This is a joke right,” wrote one reader, “on a day when gas prices are down to 1998 levels despite high demand - every agency, consultancy and producer says production is up and you trot out tired old Art Berman down from the ‘grassy knoll’ of the gas industry.”

How could I possibly say such a thing when the “shale gale” was all over the press? Didn’t I know this was a “game changer?” Why, just a month earlier the French oil major Total had bought a 25 percent stake in a shale gas play in Ohio for $2.3 billion, and China had announced a $2.3 billion investment in U.S. shale gas producer Devon Energy. Those had followed a number of other high-profile shale gas acquisitions, including the $4.4 billion buyout of Brigham Exploration Company by Norway’s Statoil in October. A week after the Statoil news, New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks joined the party, speculating about hundreds of thousands of jobs to come in the “shale gas revolution,” and noting that shale gas was “30 percent and rising” of our total gas supply.

Another reader, apparently still furious with me, recently demanded that I retract a similar statement I made in a subsequent guest post at Foreign Policy, and that I apologize for making it. “’[G]as production is not growing under current conditions’ was controversial when written, and ludicrous in hindsight,” he wrote, and then helpfully provided a link to the latest EIA data on U.S. gas production. “Notice how marketed natural gas production continues to set records, even 8 months after your claim that it is not growing,” he sneered.

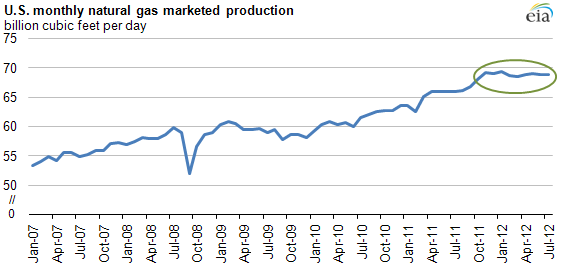

As that very data shows, U.S. marketed gas production hit a peak of 2,150,494 million cubic feet in January, 2012, the month before my articles were published. It has remained below that level ever since. Indeed, on the same day that I received that lovely email, the EIA published a short post noting that “U.S. marketed natural gas production has flattened since late 2011, mainly in response to lower natural gas prices” and providing this helpful chart:

As Art Berman had said, the shale gas “gold rush” was indeed over. That’s right: the pundits jumped on the shale gas bandwagon at precisely the moment that its growth trajectory was ending. Such is the lot of those who fail to scrutinize the data.

Readers who are unfamiliar with the nitty gritty details of shale gas might want to review my previous articles on it, in which I explained that we do not have a proved 100-year supply of natural gas, why gas production is not profitable at today’s prices, and why we should not rush in to LNG exports until we have a better idea of exactly how much gas we can produce profitably.

I will not revisit those issues in depth today; rather, I will update the shale gas story.

Production flat

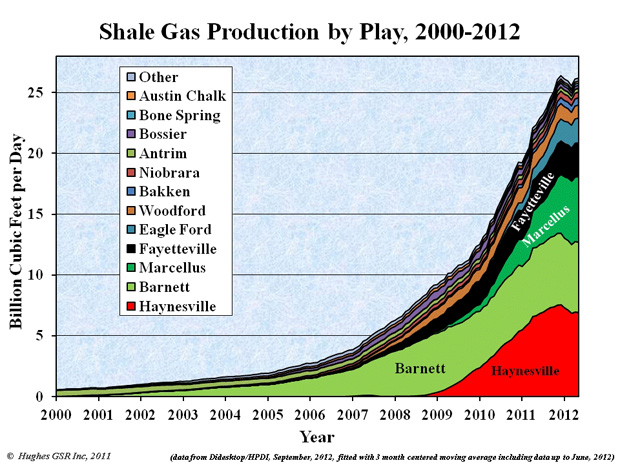

U.S. shale gas production has been basically flat — or, if you like, on an oscillating plateau — since last December. Sadly, it’s still the case that none of the public data agencies like EIA provide a reliable data set for shale gas production as distinct from total gas production, for reasons I have explained previously. But a few private data agencies with well-by-well databases do, for a hefty fee. My friend David Hughes, a retired Canadian geologist who has studied oil and gas production data for decades, recently rummaged through the HPDI database and produced the following chart of U.S. shale gas production through May 2012 (the most recent month for which reasonably complete data is available). His research will be published in a January, 2013 report for the non-profit Post Carbon Institute, including a number of charts that are sure to inflame shale gas boosters.

As of May, U.S. shale gas production stood at 27.14 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), including production in the Granite Wash, which is technically a “tight gas” (not shale gas) formation underlying parts of Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. Excluding the Granite Wash, shale gas production was 26.19 bcf/d, just slightly over the roughly 25 bcf/d produced last December.

As I indicated in my February article, production has indeed fallen in some plays, including the two most productive ones: the Haynesville Shale centered in Louisiana, and the Barnett Shale in Texas. This was entirely predictable. The Haynesville is among the least economic of the shale plays and mainly produces “dry” gas (straight methane), which is not profitable at today’s prices. The Barnett was the first shale gas play to go into major production with horizontal drilling and “fracking” in the U.S., so it’s possible (but not yet demonstrable) that its best prospects have already been depleted and producers have moved on to other plays. Hughes believes that without a real price turnaround and a major ramp-up of drilling, both the Barnett and Haynesville will continue to decline.

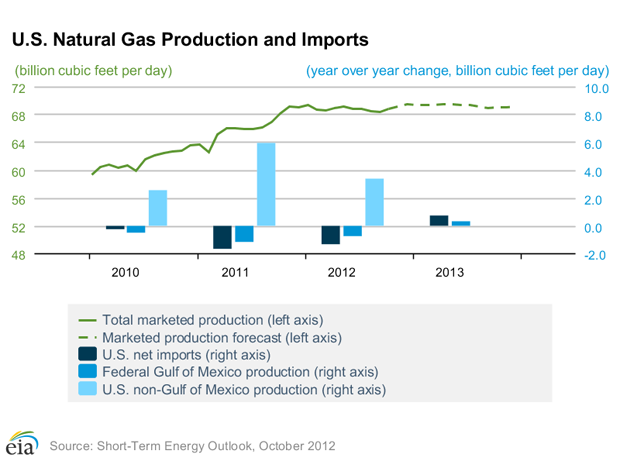

The outlook for shale gas is also basically flat. In its latest Short-Term Energy Outlook forecast, EIA sees total marketed U.S. gas production growing by just 0.4 bcf/d in 2013, or about half a percent over the September output of 68.36 bcf/d. That’s after it recovers from net declines in the coming months, which are expected as a consequence of steadily falling rig counts this year.

What happened to the “shale gale?”

There are a few reasons for the flattening of production.

First, as I expected, the price of gas has remained below the point of profitability. In the lowest-cost plays, producers need around $4 per thousand cubic feet (mcf) to turn a profit, and in the higher-cost plays it can be as high as $9 or $10. Henry Hub spot gas prices spent most of 2012 below $3 per mcf, and didn’t break $3.25 until this month. That rendered additional drilling in “dry” gas plays uneconomic.

[On a side note: The unprofitability of dry shale gas likely figured in Statoil’s decision a week ago to sell about 180 of the wells it bought a year ago. We won’t know until November what prices they’ll fetch, but I suspect they’ll be taking a write-down on those wells.]

Gas prices fell all the way to a shocking $1.82 per mcf on April 20 as the gas glut took its toll. At that price, gas might as well be free. (The equivalent amount of energy — one million BTU — in the form of West Texas Intermediate oil sells for $15.88 today.) That clearly could not continue, so five days later I suggested on Twitter that gas prices had probably bottomed. As of this writing, gas is now selling for $3.26 — almost, but not quite, back into the profitability range. In its STEO, EIA sees spot gas averaging $3.35 in 2013, but I think that’s low. I expect gas to climb back over $4 in late 2013, and so does the futures market. We won’t see a recovery in dry shale gas production until it does, and even then it will only happen in the lowest-cost plays.

Second, and more importantly, the unprofitability of dry gas drove producers to move to “wet” gas plays, like the Marcellus in Pennsylvania, which contain more-profitable natural gas liquids (NGLs). (For my detailed study on NGLs, see “Fuel to Byrne.”) A significant amount of additional gas is also being produced from “tight oil” (also known less accurately as “shale oil”) plays like the Bakken Formation in North Dakota. Tight oil is the basis of the vogue “energy independence” mania, and continues to increase at impressive rates. EIA expects it will contribute to an increase of 780 thousand barrels per day in oil production in the Lower 48 this year, and another 530 thousand barrels per day next year.

The dry gas and NGLs that are naturally associated and produced along with the oil in these tight oil formations will be produced as long as oil prices remain in their recent ranges. The only things that would drive prices low enough to put a damper on tight oil drilling are running out of good prospects to drill, which likely won’t happen for another decade, or a major market crash like the one we saw in late 2008. That gas effectively gets priority delivery into the market. This has helped to hold gas prices below the point of profitability for dry shale gas production. In short, increased fracking for oil has effectively squeezed fracked dry gas out of the market.

Finally, as I have detailed here ad nauseum, the decline rates of shale gas wells are steep. They vary widely from play to play, but the output of shale gas wells commonly falls by 50 to 60 percent or more in the first year of production. This is why I have called it a treadmill — you have to keep drilling furiously to maintain flat output. In the U.S., the aggregate decline of natural gas production from both conventional and unconventional sources is now 32 percent per year, so 22 bcf/d of new production must be added every year to keep overall production flat, according to Hughes. That’s close to the total output of U.S. shale gas, after nearly a decade of its development. It will require thousands more shale gas and tight oil wells to keep domestic gas production flat.

LNG exports increasingly dubious

With a flat outlook for gas production over the next year or more, the clamor to approve liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects continues to seem over-eager at best. A long-awaited EIA study on the impact of LNG exports on gas prices has been punted to the end of this year, and it’s unlikely that any decisions on approving additional projects — beyond Cheniere’s Sabine Pass terminal on the Louisiana border, which has already been approved for 2.2 bcf/d of export capacity — will be made until the next presidential administration is in office.

What we do know is that applications to the Department of Energy to export gas to Free Trade Agreement countries now total 27.58 bcf/d of capacity. That’s more than the entire output of U.S. shale gas. Additionally, there are pending applications for 21.06 bcf/d of export capacity to non-FTA countries.

The American people will soon need to make a choice between continuing to enjoy some of the lowest grid power costs in the developed world; a resurgence of domestic manufacturing for fertilizers, plastics and petrochemicals, conferring a significant global competitive advantage; and replacing coal-fired generation with gas… or giving all that up in order to let gas producers and exporters make a lot of money by exporting it to Europe and Asia, where it fetches up to $17 per mcf. David Greely, managing director of global investment research at Goldman Sachs, doesn’t think America will go for that, and neither do I.

Even if America does think that sounds like a good idea, an analyst at the consultancy PFC Energy isn’t so sure it would be profitable. Cited in an August post for the Wall Street Journal, he found that if exports were approved and pushed U.S. gas prices up to $7, while prices for oil in Europe fell to $90 — both in line with historical price ratios – profit margins for exports would evaporate like an uncorked canister of LNG.

As EIA chief Adam Sieminski reiterated in a presentation (PowerPoint file) a few weeks ago, the potential for U.S. shale gas remains highly uncertain. We have no good reason to rush into exporting gas before we know what its real potential and prices are, and plenty of reason to be cautious. The EIA’s modest outlook on gas suggests a real possibility that gas production could actually fall next year. The majority of our shale gas production could remain unprofitable for another year or more, and the NGL prices that have sustained it over the past year have fallen sharply as they, too, have experienced a domestic glut. None of this points to significant gas production increases in the foreseeable future. It’s time to slow down, take a sober look at the risks and costs of shale gas as well as the potential, stop thinking about fracking as a quick-fix panacea, and get back to work on a long-term energy plan for America.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.