As drought persists, many scramble to save every drop of water

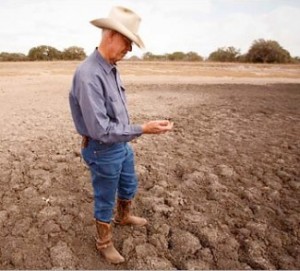

The drought that crippled many communities across the nation last year shows little sign of retreating, and the threat of persistent water scarcity is spurring efforts to preserve every drop.

The drought that crippled many communities across the nation last year shows little sign of retreating, and the threat of persistent water scarcity is spurring efforts to preserve every drop.As the drought of 2012 creeps into 2013, experts say the slow-spreading catastrophe presents near-term problems for a key U.S. agricultural region and potential long-term challenges for millions of Americans.

“Everyone is wondering whether this dry weather is the new norm … or an anomaly that will soon pass,” said Barney Austin, director of hydraulic services for INTERA Inc, an Austin, Texas-based geoscience and engineering consulting firm. “We all hope for the latter, but it’s hard to tell.”

The signs of distress and the search for answers are most prevalent in the Plains, where historic drought blankets much of Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and parts of Texas.

This month the small Oklahoma farming town of Wapanucka lost water completely when the spring-fed wells the community relies on ran dry. Officials closed schools and residents had to do without tap water until the town could run a line to a neighboring water district.

In Texas, state lawmakers are pushing for a $2 billion fund to finance water infrastructure projects as numerous communities face their own shortages. But it won’t be soon enough to help rice farmers, who were told this month that there is not likely to be enough water to irrigate their fields this spring.

Meanwhile, in the big wheat-growing state of Kansas, penalties for exceeding water use limits for irrigation were doubled this month and Governor Sam Brownback has launched a task force to come up with strategies to counter statewide shortages.

“It’s going to be dry again this year,” said Lane Letourneau, water appropriations manager for the Kansas Agriculture Department. “We consider this a really big deal.”

SEARCHING FOR SOLUTIONS

Water use is already tightly curtailed in many states. Years of low rainfall and high heat - last year was the hottest on record for the United States, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - have diminished surface waters even as population and water demand expand.

As well, agricultural and oil and gas interests are pumping the precious commodity from underground aquifers at a pace that often cannot be matched by natural replenishment.

“Water has been viewed as a basic commodity, a basic right,” said Les Lampe, a water expert with consultancy Black & Veatch. “You turn on the tap and water comes out and you don’t pay very much for it. That has to change.”

Farmers are feeling the pain of water shortages most acutely. After multibillion-dollar crop and livestock losses tied to last year’s drought, they fear more losses are coming.

Texas rice growers who depend on the lower Colorado River valley for survival are eyeing the fluctuating levels of two key lakes used for irrigation when river levels are too low.

State officials said this month that without enough rain by spring, rice farmers could be completely cut off from irrigation, jeopardizing about 2 percent of the U.S. crop and about $1 billion for the Texas economy.

“We’ve got a shortage of water,” said Ronald Gertson, a rice grower and chairman of the Colorado Water Issues Committee. “People are going to be both hungry and thirsty before they wake up to this problem.”

Forecasts show drier-than-normal weather likely prevailing in the Plains and western Midwest for the next few months at least. But even normal rainfall levels would not be enough to fully recharge resources.

Three to five times more rain than normal is needed in key corn-growing areas that include Nebraska and Kansas, for instance, to ease soil dryness after last summer’s drought, according to Don Keeney, an agricultural meteorologist with Cropcast weather service.

Roughly 60.26 percent of the contiguous United States was in at least moderate drought as of January 8, according to a “Drought Monitor” report issued by a group of federal and state climatology experts. Severe drought still blanketed 86.20 percent of the High Plains.

“This drought certainly has gotten people’s attention,” said Joe Straus, speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. “Regardless of whether it starts raining now or not, long-term water planning is essential. We need to be responsible.”

For some, it’s already an emergency. Persistent dry conditions in north-central Oklahoma led officials in Payne County to declare a state of emergency this month as the reservoir providing water to nearly 16,000 residents in seven counties fell to record low levels.

The approximately 500 residents of Wapanucka are talking of higher rates to fund a permanent pipeline to a new water source. But running out of water has shown how harsh doing without water can be, said Julie Wallis, Wapanucka’s city water clerk.

“We are not going to be the only ones who this happens to,” said Wallis. “It’s coming.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.