Lux Research Dissects Lithium-ion Battery Mythology

We all know that you can’t have a cost-effective electric car without a cost-effective battery. We also know that a small but vocal hodgepodge of ideologues, activists, politicians and dreamers wants everyone to believe that rapid and stunning advances in lithium-ion batteries will finally make the dream a reality after a century of one abject failure after another.

We all know that you can’t have a cost-effective electric car without a cost-effective battery. We also know that a small but vocal hodgepodge of ideologues, activists, politicians and dreamers wants everyone to believe that rapid and stunning advances in lithium-ion batteries will finally make the dream a reality after a century of one abject failure after another. I frequently caution readers that it won’t be anywhere near as easy as the proponents claim.

In a new report titled “Searching for Innovations to Cut Li-ion Battery Costs” Lux Research did a yeoman’s job dissecting lithium-ion battery mythology and putting the often inconsistent and invariably confusing world of battery cost claims into an understandable and comprehensive framework that:

- Explains the technical differences between various types of lithium-ion cells;

- Explains how future technological improvements will impact cell costs;

- Explains the differences between cell and battery pack costs;

- Explains the differences between nominal and useable pack capacity; and

Reinforces the inconvenient but undeniable truths that:

All lithium-ion batteries are not created equal. A critical but frequently misunderstood battery performance metric is the relationship between power and energy.

Hybrid electric vehicles, or HEVs, are power applications that typically use a small (±1.4 kWh) battery pack to absorb braking energy for immediate re-use in the next acceleration cycle. Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, or PHEVs, occupy the middle ground and use a mid-sized (5.2 to 16 kWh) battery pack to offer both hybrid and electric drive functions, which means they require both power and energy.

Battery electric vehicles, or BEVs, are energy applications that use a massive (24 to 85 kWh) battery pack to propel vehicles for long distances at high speeds. In general, HEV batteries cost more per kWh than PHEV batteries, which in turn cost more per kWh than BEV batteries. Likewise, smaller battery packs for short-range BEVs from Nissan (NSANY.PK) cost more per kWh than larger battery packs for long-range BEVs from Tesla Motors (TSLA).

Nominal cost per kWh is far lower than effective cost per kWh of useable energy. Most battery packs are designed with safety margins that reduce battery strain from operating a vehicle at a very high or a very low state of charge. Since nominal capacity is always higher than useful capacity, battery pack cost per kWh of useful energy is always higher than than nominal battery pack cost.

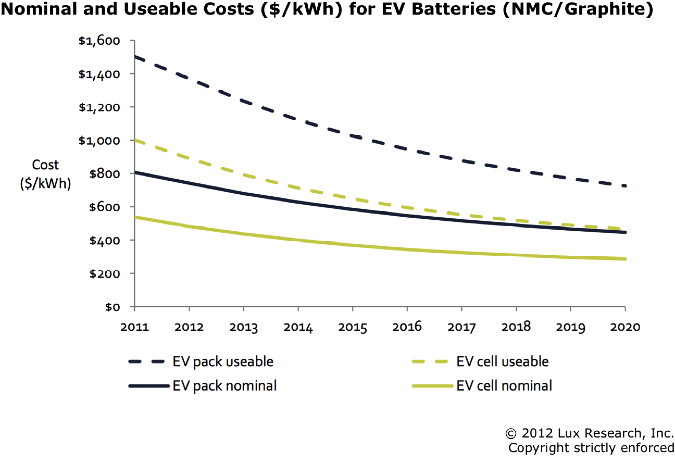

Nominal pack cost for PHEVs is currently about $800 per kWh, but the effective pack cost is closer to $1,500 per kWh of useable energy. By 2020, Lux expects nominal pack cost for PHEVs to decline to about $500 per kWh, but it believes effective pack cost will be closer to $800 per kWh of useable energy.

Nominal pack cost for BEVs is currently about $750 per kWh, but effective pack cost is closer to $1,400 per kWh of useable energy. By 2020, Lux expects nominal pack cost for BEVs to decline to about $400 per kWh, but it believes effective pack cost will be closer to $700 per kWh of useable energy.

The following graph from the Lux report shows how they expect nominal and useable costs of automotive cells and EV battery packs based on nickel, manganese, cobalt chemistry to evolve through the end of the decade. It can be particularly instructive for investors who’ve had a hard time visualizing the disparities between nominal cell and battery pack costs and effective useful energy storage capacity costs.

While the latest Lux forecasts for battery pack costs are significantly higher than most imagine based on press releases and news reports, they tie closely to comparable 2020 cost estimates from an AutomotiveWorld webinar last Thursday on “Reducing the cost of EV batteries.” While neither organization focused on the fact that the price a battery manufacturer charges an automaker doesn’t include the automaker’s integration costs or markup, the fact remains that the effective 2020 cost to the consumer will be on the order of $1,000 per kWh of useful battery capacity.

HEVs are fuel efficiency technologies that squeeze as much mileage as possible from a gallon of gasoline. In contrast, PHEVs and BEVs are fuel substitution technologies that swap a battery pack for a fuel tank so that owners can swap electricity from coal and natural gas for gasoline. Advocates wax poetic on using alternative energy to charge EVs, but the truth is the virtue of green electrons lies in their creation, rather than their use, and most drivers want to use their cars during daylight hours, which is the only time solar panels work. While electric drive can be highly efficient in runabouts like the cute Renault Twizy, it can be preposterously wasteful in rubenesque halo cars like the Fisker Karma.

HEVs are fuel efficiency technologies that squeeze as much mileage as possible from a gallon of gasoline. In contrast, PHEVs and BEVs are fuel substitution technologies that swap a battery pack for a fuel tank so that owners can swap electricity from coal and natural gas for gasoline. Advocates wax poetic on using alternative energy to charge EVs, but the truth is the virtue of green electrons lies in their creation, rather than their use, and most drivers want to use their cars during daylight hours, which is the only time solar panels work. While electric drive can be highly efficient in runabouts like the cute Renault Twizy, it can be preposterously wasteful in rubenesque halo cars like the Fisker Karma.It’s a mystery to me how EV advocates can steadfastly cling to their mythology in the face of caution from leaders like Energy Secretary Steven Chu who told participants in the November 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference:

“And what would it take to be competitive? It will take a battery, first that can last for 15 years of deep discharges; you need about five as a minimum, but really six- or seven-times higher storage capacity and you need to bring the price down by about a factor of three.”

The Secretary’s goals seem pretty straightforward:

- A 15 year life;

- Five to seven times higher storage capacity; and

- A two-thirds cost reduction.

Lux is currently forecasting a fifty percent reduction in battery costs over the next eight years in the most likely scenario, which works out to an aggressive but attainable improvement of five to six percent per year. A123 Systems (AONE) has not made significant visible progress in efforts to reduce manufacturing costs over the last three years. While Altair Nanotechnologies (ALTI) and Valence Technologies (VLNC) are a good deal more opaque than A123 Systems when it comes to providing reliable cost data to the SEC or the markets, they also seem to be having problems reducing their costs.

Investors who expect cost reduction curves like we’ve seen in electronics will be sorely disappointed. Investors who pay 17.5 times book value for a money losing startup like Tesla when they could pay 6.3 times book value for an established and extraordinarily profitable innovator like Apple will pay dearly to learn an important lesson:

– that markets may act like a voting machine in the short term, but they always act like a weighing machine in the long term.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.