What IEA’s path to net-zero emissions means for Canada’s oilsands, LNG

For years, governments and oil executives could count on the International Energy Agency to provide ammunition for continued fossil fuel investments, but with the recent release of its latest World Energy Outlook, that ammunition appears to have run out.

For years, governments and oil executives could count on the International Energy Agency to provide ammunition for continued fossil fuel investments, but with the recent release of its latest World Energy Outlook, that ammunition appears to have run out.

The annual report, released earlier this year in advance of the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) summit in Glasgow, signals a monumental shift. The era of prolonged growth in demand for oil, gas and coal seems to be coming to an end, according to the report, co-authored by energy experts from governments and industry around the world.

It describes a world that limits warming to within 1.5 C by shifting rapidly away from fossil fuels with no development of new oil and gas fields, no new or expanded coal mines and slim prospects of profits for new LNG projects.

The report follows the release of a net-zero emissions roadmap by the agency in the spring and is a sharp contrast to the messaging from industry groups like the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), and that of the Alberta government, which insist demand will continue to grow for decades and that Canada is well suited to fill the need. The report also includes some ominous projections about the economic future for Canadian fossil fuel producers.

“I think it’s the first time that the IEA scenarios that they put forward don’t include a scenario, for example, where oil growth continues out to 2050,” said Sara Hastings-Simon, a professor and director of the sustainable energy development program at the University of Calgary.

“So it’s a real shift. I think it kind of reflects an understanding of the ways that the global energy system is really changing.”

The report examines three scenarios: one that assesses the impact of current policies, a second that analyzes the impact of current pledges for new action and a third scenario that projects what would happen if the world achieves net-zero emissions by 2050 and avoids some of the worst impacts of an unstable climate.

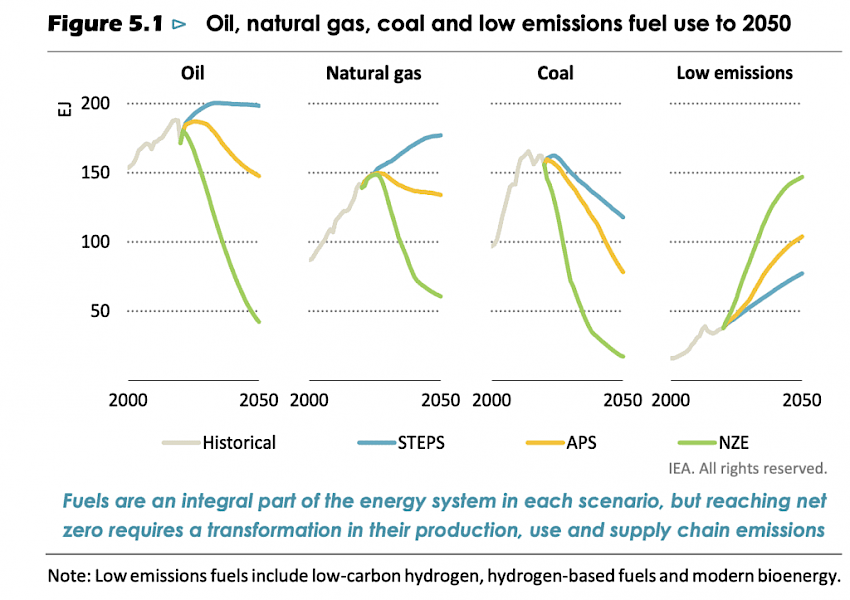

The first scenario is the only one that projects an increase in demand for oil and gas, although even then, current policies will see demand for oil plateau after 2030. Globally, coal demand will fall, while natural gas continues to climb to 2050, according to the report.

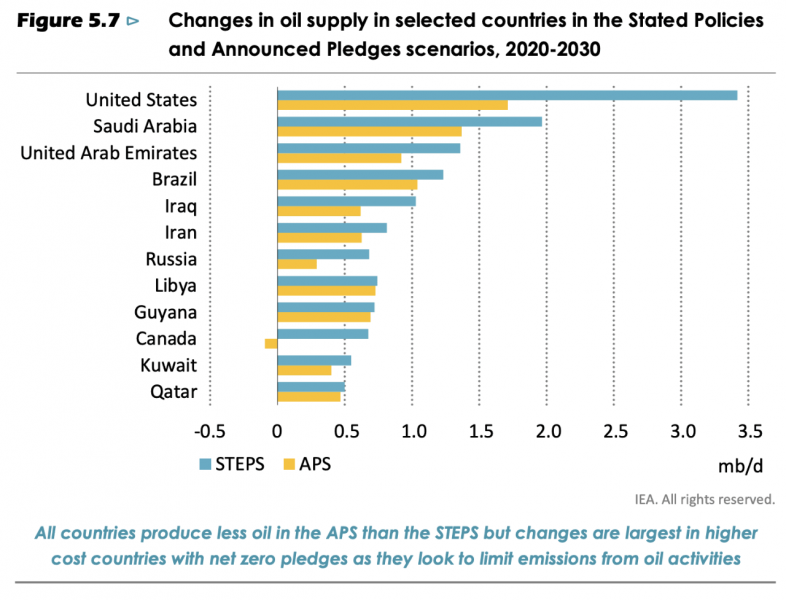

In Canada, even with policies already pledged by the government, but not yet enacted, the report’s second scenario projects the country’s contribution to global supply could dry up between now and 2030.

The report also says that, under this scenario, Canada would see “no or very limited investment into new projects from the mid-2020s.”

Any new investments would have to focus on current fields and projects in order to reduce the intensity of emissions.

In the net-zero scenario, in which humanity has the best chance of staving off a climate disaster, the agency projects a significant drop in demand for the three fossil fuels by 2030, including a 10 per cent drop in demand for natural gas, a 20 per cent drop in oil demand and a whopping 55 per cent drop in demand for coal.

The price of oil would fall to US$35 per barrel by 2030, under this net-zero scenario, which is less than half of the estimated price of US$77 per barrel under the first scenario, according to the agency’s report. That sort of price reduction would further erode investment in oil and gas, particularly in high cost areas like Canada.

The effects of a commitment to net-zero emissions would also mean LNG projects currently being built on Canada’s West Coast would likely never see a return on investment. The IEA predicts US$75 billion invested in LNG projects around the world would be stranded.

But Canada’s oil and gas industry lobby group is sidestepping these scenarios in its recent public messages, saying little about what will happen if government officials keep their climate commitments.

When asked to comment on this or on whether it disagreed with the IEA’s assertion that a net-zero scenario was critical to keeping warming to 1.5 C, CAPP explained it believes the scenarios which assume no changes in government policies have proven to be more accurate over the years.

The lobby group also defended the industry’s environmental record.

“Canada’s natural gas and oil industry is the country’s leading investor in emissions reduction and clean-technology,” CAPP President Tim McMillan said in an emailed statement.

“Investment in Canada’s natural gas and oil industry will support hundreds of thousands of jobs for Canadians and provide the foundation for our economic recovery while generating billions in government revenues to help fund emissions-reducing technologies for use in other industries and around the world.”

Hastings-Simon said CAPP’s assumption that no new climate change policies will be implemented in Canada “flies in the face of two decades of increasing policy stringency on climate,” and ignores likely changes, including electric vehicle targets.

She says the point of the IEA scenarios is so that countries can shape plans and policies against any of the future scenarios, rather than simply choosing one.

Simon Dyer, the deputy executive director of green energy think tank The Pembina Institute, says Canada, and Alberta in particular, has to start having a serious discussion about the impacts of declining demand.

“A lot of Alberta’s sort of narrative around this stuff, whether you’re talking about the war room, or the [anti-Alberta energy campaigns] inquiry, seems to suggest that this is a sort of Alberta-specific issue,” he said.

“There is actually a global conversation that’s underway that Alberta and Canada are really not actively engaged in, currently.”

The IEA report says countries need to massively ramp up investments in efficiency and renewables while doubling down on efforts that will shift consumer demands, including adoption of electric vehicles.

It also calls for focusing on electrification, carbon capture and storage and the use of hydrogen — all of which Canada has started focusing on in recent years. Alberta’s investment in petrochemicals — used in everyday goods from cosmetics to building supplies — could also provide a glimmer of hope for industry, as the only sector that sees increased demand for oil under the net-zero scenario.

The massive increase in global investment would need to go toward everything from electricity generation, to building efficiencies, to transportation and energy infrastructure, according to the IEA.

Current investments of around US$2 trillion annually need to grow to about US$5 trillion per year by 2030.

“If the world gets on track for net zero emissions by 2050, then the cumulative market opportunity for manufacturers of wind turbines, solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, electrolysers and fuel cells amounts to USD 27 trillion,” reads the report.

“These five elements alone in 2050 would be larger than today’s oil industry and its associated revenues.”

That sort of investment in new, clean technologies and efficiencies is also critical as investment in new projects dwindles and energy demands increase. But the IEA is careful to point out that recent shortages are the result of weather-related factors, planned and unplanned shutdowns and a post-recession surge in demand, rather than an energy transition.

Jennifer Henshaw, a spokesperson for Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage, said the IEA projections all show the need for continued fossil fuel use for decades and the province expects to continue selling its resources.

“Significant investments also continue to be made in Alberta’s energy sector, both to reduce emissions from existing energy sources for a lower-carbon future, and to promote growth in emerging areas including hydrogen, geothermal, renewable electricity, and rare earth minerals,” Henshaw said by email.

Hastings-Simon said Canadian companies have been working hard to reduce their emissions, but they have to work harder than other regions because they are starting from a higher carbon intensity.

She also said financial returns to governments and the benefits for workers from the oil and gas industry will diminish going forward, as companies focus on paying down debt and returning money to investors rather than spending on new capital projects.

“I think it can both be true that the world will continue to use oil for some time to come and that some of that oil will continue to come from Canada,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean that that will result in jobs and significant money flowing into the province of Alberta and to the public and to the government.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.