The year in water, 2021

Too much. Too little. Too polluted.

Too much. Too little. Too polluted.

For years these compact phrases, mantra-like in their repetition, have come to define the world’s water problems.

Now add a fourth: too frequent.

If nothing else, the last 12 months of floods, fires, droughts, and other meteorological torments delivered an uncomfortable message. Extreme events are happening more often. And they are happening almost everywhere.

Communities rich and poor bore witness to horrific devastation in 2021. In July, floods in China’s Henan province trapped commuters in subway tunnels in the city of Zhengzhou, which received as much rain in three days as it does in an average year. That same month, raging waters in Germany’s Ahr Valley scoured farmland into canyons and submerged riverside towns. Herders in northern Kenya today are lamenting the decimation of their livestock as seasonal rains failed yet again to nourish the ochre earth.

One positive trend is that severe weather is not as deadly as it was generations ago. Thanks to superior weather forecasting, early warning systems, insurance schemes, and an established network of international aid agencies, the initial blow from a flood or drought is less lethal. With advance warning, residents can find safe ground. Death tolls are typically measured in the hundreds instead of the tens of thousands.

The pain is instead distributed in other ways. Homes washed away. Dry wells. Persistent hunger after failed harvests and reliance on food aid. Rebuilding again and again like this is wearying. People on the Louisiana Gulf Coast and the Sahel, in central Africa, have come to see their homelands as places of danger. Some want to move. Their neighbors may already have.

Limiting the damage from a fevered planet was the goal of a U.N. climate summit in November. Negotiators made incremental progress in Glasgow, but the world’s carbon trajectory is still off course for keeping the global average temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above what it was two centuries ago.

Coming out of the summit, climate campaigners accused political leaders of another compact phrase — of being too timid. Low-carbon energy plans could be deployed quicker. More money could flow to poorer countries to aid adaptation to severe storms. Fossil fuel subsidies could be ratcheted down. Carbon-trapping forests and wetlands, which also filter water and calm floods, could be protected from plows and shovels.

Without a greater sense of urgency this decade, the hill to climb becomes much steeper. Future leaders don’t want to find themselves adding another phrase to the list: too late.

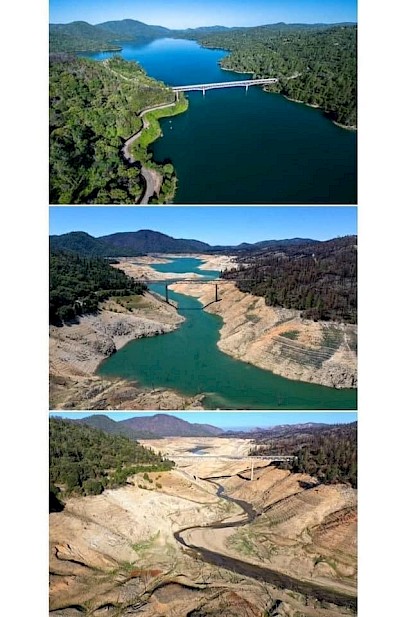

Severe Drought Challenges American West

Intense heat and meager precipitation produced tinderbox landscapes across the American West. Though no stranger to drought, the region buckled under extreme conditions. Seattle, known for mild, pleasant summers, witnessed three consecutive days of 100 degree F heat. The city had only three such days in the previous century. Hundreds of people died in the Pacific Northwest heat wave.

Water systems were at the center of the story. Lake Oroville, the second-largest reservoir in California, dropped to a record low, too depleted to generate hydropower. Wells across the region dried up, fish and birds perished, marinas closed, algae outbreaks intensified, and wildfires scorched forests and homes.

In a drying region, communities are trying to make do with less. Nevada lawmakers banned ornamental grass – the sort that fills median strips and surrounds shopping centers – in the Las Vegas area. Utah lawmakers sought to spend $50 million of the state’s pandemic relief funds on water meters for lawn irrigation. Meanwhile, a coalition of federal agencies, NGOs, and academic partners introduced OpenET, a satellite-based tool for monitoring irrigation water use.

Colorado River Basin Reaches Pivotal Moment

This year the Colorado River basin’s unforgiving math — too many promises of water and too little actual water — began to hit home. Lakes Mead and Powell, the country’s largest reservoirs, fell to record lows. The federal government declared a first-ever Tier 1 shortage, which meant mandatory water cuts for Arizona and Nevada.

The events of 2021 are likely to be only a prelude for sterner tasks ahead. The basin is overallocated. The region is drying. Though residents are trying to use less water, they can’t live with none. It is up to all parties in the basin to ensure that the unforgiving math does not work out to an answer of zero water.

The Colorado River basin, said John Matthews, executive director of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, is a place “where we only have hard choices now.”

U.S. Water Access and Affordability

The U.S. government took a major step toward revitalizing the nation’s water systems when President Biden signed the $1.2 trillion infrastructure package on November 15. That is in addition to hundreds of billions in the American Rescue Plan Act that state, local, and tribal governments can use for urgent system repairs.

The funding is needed. Water utilities around California’s Clear Lake faced extraordinarily high levels of cyanobacteria that are clogging their equipment. Small communities in Michigan wondered where the money would come from for repairing sewers and removing lead pipes. The $15 billion included in the infrastructure bill for lead pipe replacement could help towns like Benton Harbor, the latest Michigan community to struggle with dirty water.

At the same time, municipalities continue to sue chemical companies over PFAS contamination of groundwater and rivers. Utilities from Alabama to Vermont have settled lawsuits for tens of millions of dollars – money that will help pay the cost of water treatment, chemical cleanup, and connecting homes with polluted wells to municipal water.

Covid and WASH

The coronavirus pandemic presented water utilities around the world with one of their biggest challenges. When cities and nations locked down their people to combat the virus, economic activity slowed considerably. Analysts were broadly concerned about two outcomes: customers not being able to pay their bills and utilities not having enough revenue to maintain service.

This year showed that fears of a worst-case scenario were largely unfounded. Even as the global poverty rate rose for the first time in two decades and more people in developing countries were thrust into poverty, utilities proved more resilient than expected.

Still, the pandemic did inflict acute financial distress on residents who lost jobs and fell behind on bills. Progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals for drinking water, sanitation, and water management slowed.

In the United States, some utilities experienced supply chain problems and had difficulty securing water treatment chemicals. Advocacy groups, meanwhile, cheered the passage of the first-ever federal program to assist low-income households with paying off overdue water bills. But the program has been slow to get off the ground. No payments on behalf of households had been made as of mid-November.

Disasters Disrupt Water

A deep freeze in Texas. Hurricane damage in Louisiana. Fires in California that shrouded the sky and lasted for months. Each hazard, in its own way, exposed the vulnerabilities of water systems to climate shocks. The Texas freeze, which extended into Louisiana and Mississippi, caused pipes to burst and left millions without water for several days. The water system in Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, was so deeply damaged from the event that it had a boil-water advisory in place for a month.

Academics refer to incidents like these as “compounding” disasters — when, for example, a power outage cripples a wastewater plant that then floods rivers and streets with untreated sewage. Or when heavy rains wash sediment and debris from a fire-scorched hillside into a reservoir, clogging a utility’s drinking water intake.

The pace of such multifaceted disasters is unlikely to slow. People continue to move into risky terrain while aging infrastructure and misguided land developments, like draining and paving flood-buffering wetlands, prove inadequate to the moment. A study based on satellite data revealed that the number of people living in floodplains grew by 58 million to 86 million between 2000 and 2015.

“We are creating risk even faster than we can mitigate it,” said Alessandra Jerolleman, an assistant professor of emergency management at Jacksonville State University. “Even if we didn’t have climate as a compounding factor.”

Indigenous Groups Seek Voice in Water Decisions

Indigenous groups across the continents put themselves at the front lines of environmental protection, often at great personal and community risk.

By protesting against the Line 3 oil pipeline project in Minnesota or opposing dams in the Mekong basin that could damage important fisheries and wetlands, activists opened themselves to the threat of retaliation. An Indigenous campaigner in Honduras who was protesting a hydropower dam on the Ulúa River was shot and killed outside his home. His death was the latest in a string of attacks in recent years against environmentalists in Latin America.

Even in academia, Indigenous voices still struggle to be heard. In climate research in Alaska, Native communities are seeking greater representation of their oral traditions and centuries-old knowledge.

Technology and Adaptation

With the realities of a warming planet becoming clearer, communities are learning they cannot duck every punch. How to absorb some blows and bounce back is part of the renewed emphasis on adaptation.

Some adaptations result in physical changes. A small town in Illinois changed its development patterns after being flooded one time too many. Cape Town, three years after its Day Zero close call, is restoring native forests in the watersheds that feed its reservoirs so it can avoid another water crisis. In the wastewater sector, technological changes — from equipment that captures the energy in sewage to sensors that monitor sewer system capacity and reduce the risk of overflows — could transform the profession.

Other adaptations require political agreement. States in the Colorado River basin are working to reduce water use to keep lakes Mead and Powell from collapsing. Jordan and Israel signed a pact to swap renewable energy for desalinated water. And the U.S. and Mexico advanced plans to clean up sewage pollution in the Tijuana River watershed.

Climate Change Brings Water Risks

In northern Kenya, cattle carcasses putrefy on sunbaked ground, casualties of the region’s unforgiving drought. In China’s Henan province, subway commuters were trapped underground this summer when flash floods inundated the rail tunnel. These scenes were repeated in New York City’s subways during Hurricane Ida, in September. In British Columbia, a convoy of moisture-rich storms encircled the region with landslides and floods, cutting off major road and rail corridors that will take months to repair.

More of these events are to be expected as the planet continues to warm, according to the U.N. climate change panel’s most recent report, which noted that a buildup of greenhouse gases is intensifying the water cycle. Big rains are more likely to swell into monster storms because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture. Higher heat will amplify droughts, as is the case in the Colorado River basin.

“We now have increased evidence that extreme events are becoming both more frequent and more severe,” said Matthew Barlow, a professor of climate science at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

These extreme events are an economic risk. Countries that rely on hydropower dams for a large portion of their electricity supply can face shortages when the rains fail. It happened this year in Brazil, where low reservoirs caused hydropower generation to plunge. Power companies turned instead to natural gas — but also displayed new interest in wind and solar.

They are environmental and public health risks, too. Witness the salmon suffocating in Northern California streams and the explosive growth of harmful algal blooms in lakes.

Weather and climate shifts can also lead to social unravelings. People leave home when they feel that their prospects are dim. World Bank research found that droughts are more likely to spur people to migrate than floods.

Is Michigan Ready for Climate Change?

The Great Lakes region, and Michigan in particular, is touted as an area well-positioned for a warming future. But is it?

This collaborative reporting project, a joint effort of Bridge Michigan, Circle of Blue, Great Lakes Now at DPTV, and Michigan Radio, sought to answer that question.

The project found that Michigan, though it has potential to be a haven in turbulent environmental times, still has much work to do to match its infrastructure and policies to the sometimes harsh realities of a 21st century climate. The shortcomings were obvious this year. Powerful rain storms this summer overwhelmed antiquated drainage systems in Chicago and Detroit, flooding highways and homes. Rural communities wondered where they would find funding to fix old water systems and remove lead pipes. Native American tribes, not to be left out of the conversation, want their treaty rights respected and a voice in policy decisions that affect land and waters.

HotSpots H2O

Water is both a source of tension and a casualty of war. In the end, it is the people who suffer.

Circle of Blue’s weekly HotSpots series highlights areas in which water access plays a role in civic upheaval and armed conflict.

Conflict unfurled this year on stages large and small. Israeli airstrikes in May damaged water and sewer systems in Gaza. The harm these attacks inflict on vital infrastructure and children was described in a UN report on water systems in wartime. Meanwhile, lack of water again proved to be one of Iran’s biggest social and political risks, as water cuts resulted in deadly protests in Khuzestan province, where at least nine people died.

Elsewhere, severe droughts in Kenya and Madagascar put millions of people at risk of hunger and starvation.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.