The Coral Reef Crisis Threatens Nature's Ability To Help Us Deal With Climate Change

As a marine scientist, and surfer, I’m always initially surprised when I hear that many island folks, like most of my friends in Eleuthera (Bahamas), are scared of the sea. That’s of course before I quickly remind myself that people on Eleuthera (an island that averages about 2 miles wide across its 90 mile length), have survived one too many storms – like Hurricane Irene, whose eye gazed directly on them last August 25.

Indeed, like my friends in the Bahamas, billions of people around the world are exposed to risks from coastal storms and flooding – risks that are causing more costly damage to people and property than ever before. In fact, Munich Re estimated that the total cost of all natural disasters globally in 2011 reached an all-time high of $380 billion – almost double the previous record of $220 billion, set in 2005.

But not all storms and other natural hazards need to turn in to disasters. That is a core message of the just released 2012 World Risk Report, led by the Alliance for Development Works, United Nations University, and The Nature Conservancy.

In addition to assessing the countries most at-risk globally through the World Risk Index, this year’s report focuses on the role of the environment in reducing risk and the effects of environmental degradation on increasing risk to people.

The report also comes two days before the UN’s International Day for Disaster Reduction.

Reefs and Mangroves Are Cost-Effective for Risk Reduction.

In the Report, my Conservancy colleague, Christine Shepard and I highlight the incredible role that reefs and wetlands can play in helping to reduce risks for people from natural hazards

Coral reefs, oyster reefs and mangroves offer flexible, cost-effective, and sustainable risk reduction benefits. Reefs have a huge impact on the force of waves reaching coasts –reefs reduce wave energy by more than 85 percent – making them natural breakwaters and the first line of coastal defense for communities. In addition, reefs and marshes offer other benefits like healthy fisheries and tourism that sea walls and artificial breakwaters will never provide.

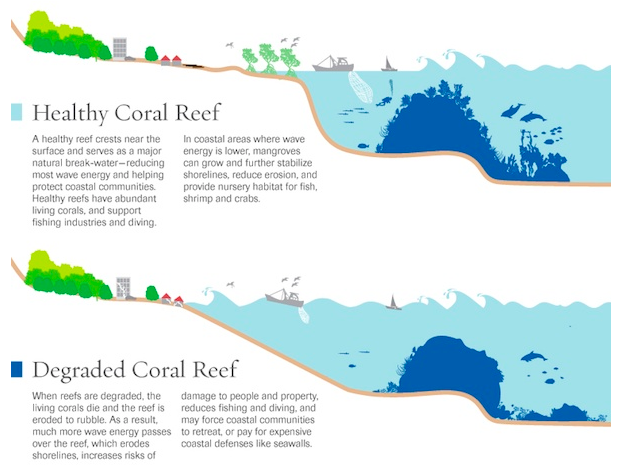

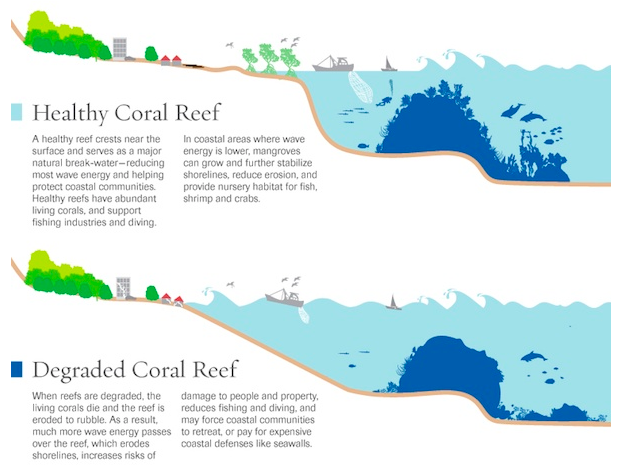

Figure 1: Healthy and Degraded Coral Reef

What’s more, the number of people that potentially benefit from coral reefs is huge. Some 200 million people live in low and exposed villages, towns, and cities (below 10 meters elevation) AND near a reef (within 50 kilometers) that may offer them direct and indirect benefits (see Fig 1).

These are also the communities and municipalities that might bear coastal defense costs or other development costs if reefs are degraded and more artificial barriers and hardened shorelines (“gray” infrastructure) must be developed.

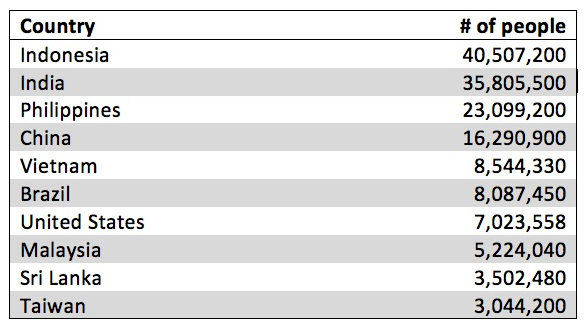

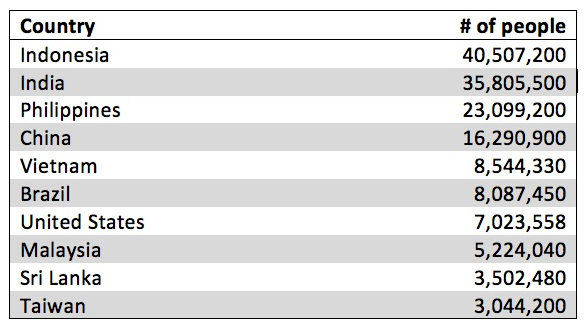

Figure 2: Top-10 Countries where coral reefs may offer the greatest risk reduction benefits. Chart based on number of people living at less than 10 meters above sea level; and within 50 kilometers of a coral reef.

To Do the Best Job, We Must Value “Green Infrastructure” Alongside “Gray.”

Many decisions and investments for coastal protection are being made today. The concern is that most money will go to gray infrastructure (artificial breakwaters and seawalls) – with further detrimental effects on coasts and habitats, expensive maintenance costs and no other benefits beyond their protective service.

Green infrastructure solutions, like reef and mangrove conservation and restoration, are viable and cost effective alternatives.

For example, in the Gulf of Mexico, The Nature Conservancy and partners are restoring oyster reefs for coastal defense at approximately $1 million USD per mile, which is comparable or cheaper than “gray” breakwater costs, and that’s before even considering the economic and quality of life benefits to fisheries, recreation and tourism that the oyster reefs provide.

But don’t just take it from our experience. For example, in a report released last year, the insurance industry identified that reef and mangrove restoration are some of the most cost effective risk reduction solutions in the Caribbean.

What’s more, The World Risk Index shows that the top 15 most at-risk nations globally are all tropical and coastal – exactly where mangroves and reefs are the most relevant.

How and Where to Act.

Conservation groups like The Nature Conservancy as well as disaster relief and development groups, like the Alliance for Development Works, Oxfam and CARE, are prepared to help governments, nationally and multi-nationally, identify where coastal habitats are viable solutions for risk reduction and place priority on their conservation & restoration.

Understanding the overlap in social and environmental risk is critical for informing how and where to act. Some of the nations identified as most at-risk by the World Risk Index are in the western Pacific in Oceania.

These countries also have more than a quarter of their entire populations in low elevations and near reefs (28%) – the largest proportion in the world. Fortunately these are the areas where reefs are also in the best shape globally. In Oceania, we need to concentrate efforts on reef conservation, because if reefs are degraded it will have serious consequences for people already often at high risk.

In many other areas, reefs are in worse shape and countries and civil societies need to focus on restoration and better management, which can have a real influence on reducing risk.

As I mentioned at the start, nations throughout the Caribbean have very high exposure to storms. The role of barrier reefs and their restoration is particularly important there. Meanwhile, Asia has by far the greatest number of people (127M) in low elevations near reefs, and is thus where reef restoration would benefit the most people.

The benefits from natural solutions are real, but not a panacea. Indeed no defense guarantees protection; even the largest and most fortified barriers fail to offer complete protection (e.g., Japanese tsunami). It is also possible for any defense – green or gray – to funnel waters in ways that can increase hazards in other areas; barriers do not stop water, they redirect it.

Bottom line: green infrastructure solutions for coastal protection to people and property must be valued alongside gray solutions.

And, to maximize the cost-effective opportunity that green infrastructure affords us, government agencies and environmental organizations need to change the way that we work to focus more on conservation and restoration efforts that are clearly targeted for vulnerable people.

This will mean working less often in more remote areas and much more often where reefs and mangroves are closest to people, and where their protection and restoration can provide the greatest benefits to the most people.

Indeed, like my friends in the Bahamas, billions of people around the world are exposed to risks from coastal storms and flooding – risks that are causing more costly damage to people and property than ever before. In fact, Munich Re estimated that the total cost of all natural disasters globally in 2011 reached an all-time high of $380 billion – almost double the previous record of $220 billion, set in 2005.

But not all storms and other natural hazards need to turn in to disasters. That is a core message of the just released 2012 World Risk Report, led by the Alliance for Development Works, United Nations University, and The Nature Conservancy.

In addition to assessing the countries most at-risk globally through the World Risk Index, this year’s report focuses on the role of the environment in reducing risk and the effects of environmental degradation on increasing risk to people.

The report also comes two days before the UN’s International Day for Disaster Reduction.

Reefs and Mangroves Are Cost-Effective for Risk Reduction.

In the Report, my Conservancy colleague, Christine Shepard and I highlight the incredible role that reefs and wetlands can play in helping to reduce risks for people from natural hazards

Coral reefs, oyster reefs and mangroves offer flexible, cost-effective, and sustainable risk reduction benefits. Reefs have a huge impact on the force of waves reaching coasts –reefs reduce wave energy by more than 85 percent – making them natural breakwaters and the first line of coastal defense for communities. In addition, reefs and marshes offer other benefits like healthy fisheries and tourism that sea walls and artificial breakwaters will never provide.

Figure 1: Healthy and Degraded Coral Reef

What’s more, the number of people that potentially benefit from coral reefs is huge. Some 200 million people live in low and exposed villages, towns, and cities (below 10 meters elevation) AND near a reef (within 50 kilometers) that may offer them direct and indirect benefits (see Fig 1).

These are also the communities and municipalities that might bear coastal defense costs or other development costs if reefs are degraded and more artificial barriers and hardened shorelines (“gray” infrastructure) must be developed.

Figure 2: Top-10 Countries where coral reefs may offer the greatest risk reduction benefits. Chart based on number of people living at less than 10 meters above sea level; and within 50 kilometers of a coral reef.

To Do the Best Job, We Must Value “Green Infrastructure” Alongside “Gray.”

Many decisions and investments for coastal protection are being made today. The concern is that most money will go to gray infrastructure (artificial breakwaters and seawalls) – with further detrimental effects on coasts and habitats, expensive maintenance costs and no other benefits beyond their protective service.

Green infrastructure solutions, like reef and mangrove conservation and restoration, are viable and cost effective alternatives.

For example, in the Gulf of Mexico, The Nature Conservancy and partners are restoring oyster reefs for coastal defense at approximately $1 million USD per mile, which is comparable or cheaper than “gray” breakwater costs, and that’s before even considering the economic and quality of life benefits to fisheries, recreation and tourism that the oyster reefs provide.

But don’t just take it from our experience. For example, in a report released last year, the insurance industry identified that reef and mangrove restoration are some of the most cost effective risk reduction solutions in the Caribbean.

What’s more, The World Risk Index shows that the top 15 most at-risk nations globally are all tropical and coastal – exactly where mangroves and reefs are the most relevant.

How and Where to Act.

Conservation groups like The Nature Conservancy as well as disaster relief and development groups, like the Alliance for Development Works, Oxfam and CARE, are prepared to help governments, nationally and multi-nationally, identify where coastal habitats are viable solutions for risk reduction and place priority on their conservation & restoration.

Understanding the overlap in social and environmental risk is critical for informing how and where to act. Some of the nations identified as most at-risk by the World Risk Index are in the western Pacific in Oceania.

These countries also have more than a quarter of their entire populations in low elevations and near reefs (28%) – the largest proportion in the world. Fortunately these are the areas where reefs are also in the best shape globally. In Oceania, we need to concentrate efforts on reef conservation, because if reefs are degraded it will have serious consequences for people already often at high risk.

In many other areas, reefs are in worse shape and countries and civil societies need to focus on restoration and better management, which can have a real influence on reducing risk.

As I mentioned at the start, nations throughout the Caribbean have very high exposure to storms. The role of barrier reefs and their restoration is particularly important there. Meanwhile, Asia has by far the greatest number of people (127M) in low elevations near reefs, and is thus where reef restoration would benefit the most people.

The benefits from natural solutions are real, but not a panacea. Indeed no defense guarantees protection; even the largest and most fortified barriers fail to offer complete protection (e.g., Japanese tsunami). It is also possible for any defense – green or gray – to funnel waters in ways that can increase hazards in other areas; barriers do not stop water, they redirect it.

Bottom line: green infrastructure solutions for coastal protection to people and property must be valued alongside gray solutions.

And, to maximize the cost-effective opportunity that green infrastructure affords us, government agencies and environmental organizations need to change the way that we work to focus more on conservation and restoration efforts that are clearly targeted for vulnerable people.

This will mean working less often in more remote areas and much more often where reefs and mangroves are closest to people, and where their protection and restoration can provide the greatest benefits to the most people.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.