Oil disrupter: Startup's tech turns natural gas into chemicals

The boom in natural gas production in North America is often viewed as a great disrupter to coal-fired power plants. But what about oil?

The boom in natural gas production in North America is often viewed as a great disrupter to coal-fired power plants. But what about oil?San Francisco-based startup Siluria Technologies is working to commercialize a process that replaces oil with natural gas to make chemicals, plastics and transportation fuels like gasoline, jet fuel and diesel.

It’s a provocative and potentially profitable endeavor. The fuels and chemicals Siluria can make are indistinguishable from products made from oil. The only difference is cost.

Natural gas is vastly cheaper and more abundant than oil. Natural gas and oil is four to five times less expensive than oil in North America and nearly half the price of crude in Europe.

And the company says it chemical process is more efficient and flexible than other conventional gas-to-liquids technology. (Scroll down to read about the process in detail). The chemical process is especially attractive because it works with existing infrastructure used by the petrochemical and oil and gas industries.

Siluria’s process has attracted the interest and dollars from high-profile investors, including Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers. Siluria announced last week it raised $30 million in a financing round led by new investors Bright Capital and Paul Allen’s fund Vulcan Capital. To date, Siluria has raised $63.5 million.

Siluria will use the monies to fund the construction of a demonstration plant next year and commercialize its technology.

Siluria President Alex Tkachenko doesn’t see the process as displacing oil altogether. And told me in a recent interview that he’s doesn’t want to project an impression that the company expects to revolutionize an industry worth a trillion dollar over night.

However, the repercussions over the long-term could be revolutionary, Tkachenko said.

“When oil came around it took many decades to significantly impact coal consumption — and we’re still not completely done with it — but look how it transformed the world,” he said. “That’s kind of how we think about our work.”

Of course, this all hinges on Siluria’s ability to raise enough funds from investors, industry partners and future customers to commercialize to bring its process to market.

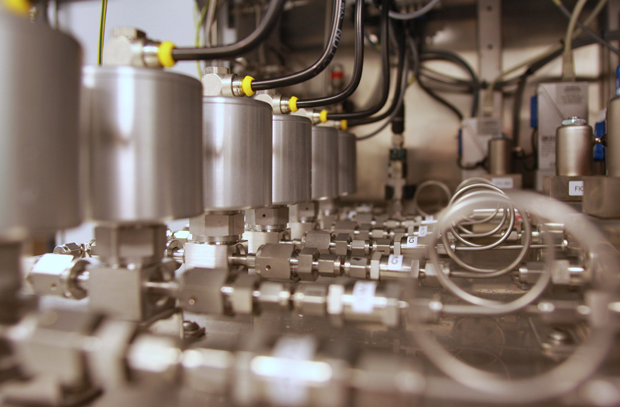

Tkachenko wouldn’t give a detailed timeline to commercialization, saying only that it would likely be less than five years and more than one. The company’s first task is to build the demonstration plant and test equipment to determine which types of reactors, pumps, compressors fit together best and most economically.

The demonstration plant will be located closer to a source of natural gas and an industrial setting. Tkachenko says the company will likely partner with a company in either the petrochemical or oil and gas industry.

How it works

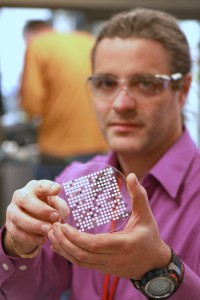

MIT Professor Angela Belcher initial devised the science behind the company. Since 2009, Tkachenko and Erik Scher, vice president of research and development, have expanded the company’s based of intellectual property.

The company used biotechnology to create thousands of test catalysts to find one that would best enable a process called oxidative coupling of methane at comparatively low temperatures.

The catalyst is combined with methane, which consists of a carbon atom surrounded by four hydrogen atoms, to produce ethylene. Those ethylene molecules, which consists of two carbons and four hydrogen atoms, can then be strung together, like beads on a string, to produce gas or diesel, jet fuel or polymers, according to the company.

Conventional gas-to-liquids technology uses the Fischer-Tropsch process, which involves breaking methane down into constituent components and building it back up. This high-temperature process creates a soup of hydrocarbons that must be separated, a complex and expensive endeavor. GTL plants that use the Fischer-Tropsch process cost billions of dollars, take years to build and typically must be located near a large natural gas resource, such as Shell’s Pearl GTL facility in Qatar.

Siluria’s process eliminates these steps and, as a result, is considerably cheaper. Tkachenko said if conventional GTl plants cost tens of billions of dollars, Siluria’s technology would cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars range.

A Siluria plant could be built next to the source of the natural gas, say near drilling sites in Texas and North Dakota, or adjacent to large petrochemical companies along the Gulf Coast.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.