Island Wildlife Decline, Linked To Ocean Acidification

The NY Times published a sobering piece recently about Tatoosh Island off the coast of Washington state. Tatoosh is a global “warming bellwether”:

The NY Times published a sobering piece recently about Tatoosh Island off the coast of Washington state. Tatoosh is a global “warming bellwether”: But for over four decades, with the blessing of Makah leaders, Tatoosh has been the object of intense biological scrutiny, and scientists say they are seeing disturbing declines across species — changes that could prove a bellwether for oceanic change globally.

The Makah hold treaty rights to the island.

Among the declines the researchers are noticing: historically hardy populations of gulls and murres are only half what they were 10 years ago, and only a few chicks hatched this spring. Mussel shells are notably thinner, and recently the mussels seem to be detaching from rocks more easily and with greater frequency.

Goose barnacles are also suffering, and so are the hard, splotchy, wine-colored coralline algae, which appear like graffiti along rocky shorelines.

This particular whodunit appears to be largely solved: Humans in the Ecosystem with CO2. Global warming is “capable of wrecking the marine ecosystem and depriving future generations of the harvest of the seas”.

In this case, it’s ocean acidification, a subject we have covered extensively — see, for instance, Geological Society study finds acidifying oceans on track for marine biological meltdown “by end of century,” as co-author warns: “Unless we curb carbon emissions we risk mass extinctions, degrading coastal waters and encouraging outbreaks of toxic jellyfish and algae.”

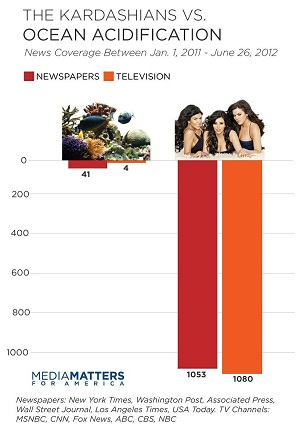

The major media haven’t been so focused on this major threat to humanity

The major media haven’t been so focused on this major threat to humanity So it’s good to see the Times run with this story and explain the climate change angle so clearly:

Biologists suspect that the shifts are related to huge declines in the water’s pH, a shift attributed to the absorption of excess carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere in ever-greater amounts by the burning of fossil fuels for energy.

As the carbon dioxide is absorbed, it alters the oceanic water chemistry, turning it increasingly acidic. Barnacles, oysters and mussels find it more difficult to survive, which can cause chain reactions among the animals that eat those species, like birds and people.

During a research trip in 2000, Dr. Pfister and Dr. Wootton first began testing the pH of water samples. They found the water around Tatoosh and along nearby coastlines to be 10 times as acidic as what accepted climate change models were predicting. Even after collecting seven years of data, when they published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2008, their data were met with skepticism.

“People think we just don’t know how to use the instrument — I still hear that,” Dr. Pfister said. “Luckily for our reputations, I guess, this has been corroborated by a lot of other people.”

Unluckily for humanity, a great many of the impacts of man-made greenhouse gas emissions are worse than what “accepted climate change models were predicting.”

It was on Tatoosh and the nearby shore (which you can see in the top photo) that Prof. Robert T. Paine, retired University of Washington zoologist, “developed his keystone species hypothesis, which describes how top predators dominate an ecosystem, often to the benefit of species diversity.” I guess that makes us the anti-keystone species, since humans dominate almost every ecosystem, but invariably to the detriment of species diversity.

Indeed, we seem to be the species that is especially adept at wiping out keystone species and diversity

The final word goes to the too-appropriately named professor:

“You can predict change,” Dr. Paine said, “and most of the changes are going to be in a direction we don’t want.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.