India's other power failure (and its opportunity)

India’s massive blackout earlier this week exposed a much bigger, more complex problem that’s been festering in the world’s second-most populous nation for decades.

India’s massive blackout earlier this week exposed a much bigger, more complex problem that’s been festering in the world’s second-most populous nation for decades.The blackout, which snarled traffic, halted commuter services and disrupted telecommunications operations, was a mere distraction to India’s bigger power failure.

The grid failure, which was the second blackout in two days, affected the east and northern regions of India, where an estimated 680 million people live, the WSJ reported.

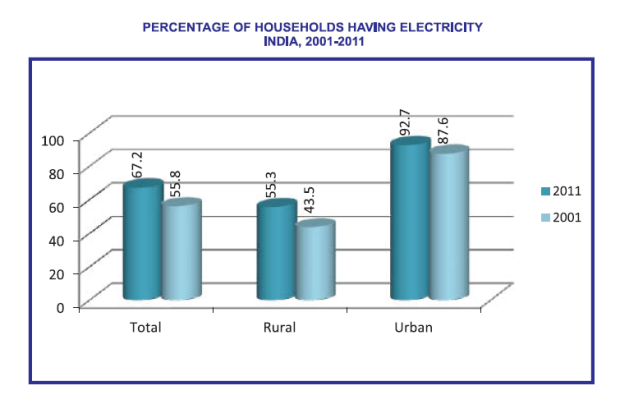

The actual number of people who lost power is likely much lower because about 50 percent of the population in this part of country already lives without electricity. According to India’s 2011 census, 67.2 percent of the country’s total population has electricity. Those figures are much lower in rural regions of the country, where the percentage of households with electricity is as low 23 percent in one state.

Indian engineer and entrepreneur Harish Hande gave his inside view to Andrew Revkin at the New York Times. He wrote:

It’s interesting that the rich in the states without power are complaining the most, about how they are suffering because of no air condtioners, etcetera. Yet 400 million Indians today still have not seen a light bulb while 200 million more regularly suffer from regular brownouts (between 6 and 19 hours).

India’s power grid suffers from numerous problems. The network loses 27 percent of the power it carries through dissipation from wires and theft and peak supply falls short of demand by an average of 9 percent, Bloomberg reported.

Meanwhile, India’s appetite for energy continues to grow. The Energy Information Administration’s International Energy Outlook 2011 projects electricity consumption in India will grow at an average of 3.3 percent a year through 2035. India will have to expand its power capacity by 234 gigawatts to meet that growth in demand, according to the EIA.

India has set capacity and infrastructure targets over the years. It’s failed to meet every power capacity target since 1951, Bloomberg reported.

For example, India’s Ministry of Power set a goal back in 2003 to provide “Power for all” by 2012. And the country was only able to meet about 64 percent of its target to add 78,000 megawatts of generation between 2007 and 2012.

The solution will require far more than simply adding capacity. The country’s infrastructure is weak, electricity theft is rampant and inefficiency is widespread. Hande suggests a broader, more inclusive strategy that includes urban planning to ensure homes are designed for better lighting and incorporate renewable energy, such as solar.

Solar potential

Renewable energy, notably solar, is one bright spot. If the opportunity and benefit of solar wasn’t apparent before, the blackout might have helped articulate the point. Rural villagers who once lived without power were able to keep the lights on because of recently installed solar panels.

Renewable energy, notably solar, is one bright spot. If the opportunity and benefit of solar wasn’t apparent before, the blackout might have helped articulate the point. Rural villagers who once lived without power were able to keep the lights on because of recently installed solar panels.The United Nations Environment Programme’s Global Trends Report found India invested $12 billion in renewable energy in 2011, marking a 62 percent increase from the previous year.

India’s National Solar Mission, which has a goal of installing 20 GW of grid-connected solar and 2 GW of off-grid solar by 2022, has attracted project developers, solar manufacturers and investors hoping to capture a piece of the renewable energy pie.

U.S. manufacturer First Solar established in May 2012 an operating company in India as part of the company’s strategy to expand the market for utility-scale solar photovoltaic power plants.

Off-grid projects also are underway. SunEdison, subsidiary of MEMC Electronic Materials, officially kicked off its Eradication of Darkness program in late May. SunEdison installed a 14-kilowatt solar-powered microgrid in a remote Indian village, the first of potentially 30 rural electrification projects the company hopes to add in India over the next year or so.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.