How Should We Talk About Climate Change With Farmers?

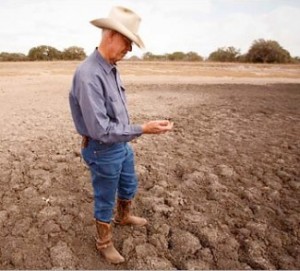

At a gathering of ranchers in Kansas City last weekend, every meeting and meal was opened with a prayer, including a plea for rain to end this devastating drought. Drought-caused price spikes for feed are forcing many livestock producers to slaughter their herds to a level they can afford to feed. You won’t often see a direct link in these stories to climate change, and you are even less likely to hear such a link made by the farmers and ranchers themselves. The key is to understand farmers’ perspectives, be strategic about effective engagement and find common ground.

At a gathering of ranchers in Kansas City last weekend, every meeting and meal was opened with a prayer, including a plea for rain to end this devastating drought. Drought-caused price spikes for feed are forcing many livestock producers to slaughter their herds to a level they can afford to feed. You won’t often see a direct link in these stories to climate change, and you are even less likely to hear such a link made by the farmers and ranchers themselves. The key is to understand farmers’ perspectives, be strategic about effective engagement and find common ground.Farmer Attitudes

While working to help the David & Lucile Packard Foundation develop their grantmaking program aimed at improving the environmental footprint of agriculture, I was part of a team that researched the attitudes of conventional farmers on issues such as conservation programs, subsidies, and climate change. Through dozens of interviews with producers mostly in the Midwest in 2010, we came away with valuable insights that should be taken into consideration when developing strategies to engage farmers and ranchers in environmental issues, and particularly the climate issue.

Most of the farmers we talked to participated in both federal farm subsidy programs and conservation programs, most were large — average 2400 acres — and many were under age 65, excited about technology, embracing thoughtful change in operations, and internet savvy. Many have “conservation-positive” perspectives, have adopted no-till practices (that reduce soil erosion, water input, air pollution and climate impact from fuel used to till), were open-minded about farm policy changes, and only mildly anti-government. They are proud of their role as “stewards of the land.”

Climate Change is a non-starter

Despite this pro-conservation bent, very few farmers believe climate change is a serious issue caused by human behavior. Most feel it’s a “political ploy” by Al Gore, and most echoed similar talking points about “natural cycles.” Even believers warn against “being fanatical.” And while most don’t believe ethanol is the answer to energy independence, they support biofuels as a market, which has provided a much-needed additional source of income.

Language is critical

The words “environment” or “sustainable” can mean very different things to them. For most, “sustainable” means being able to keep their business running for another year. Many farmers feel the public doesn’t understand or appreciate them for the hard work they do as stewards of the land, the financial risk they take on, and their dedication to producing abundant, safe, affordable food.

Many farmers also hold the belief that environmental regulations are part of the reason they are struggling to make ends meet. How much truth that belief has doesn’t really matter. To change production practices in ways that will deliver more environmental benefits, producers need to be convinced of an economic return on investment in change.

Opportunities for engagement

One of most important findings is the existence of a long-simmering, and increasingly urgent, feeling among family farmers that they are being squeezed, subjugated, and forced out of business by large corporations. Agriculture is being “Walmart-ized” in the words of some. And while this came as a surprise to some of us who have seen how incredibly powerful the farm lobby is in federal legislation, most of the farmers we talked to don’t feel they have a significant voice on policy. They believe the Farm Bureau, commodity organizations and elected leaders have all the influence, and that they are up against the strength of corporate interests and environmental forces.

As I mentioned, I recently returned from a gathering of independent family-owned ranchers in Kansas City, MO sponsored by the Organization for Competitive Markets. These guys have been at it for 14 years trying to fight the trend towards mega-corporate consolidation of livestock production. They are losing. Four huge companies own huge majorities of the beef, pork and poultry produced in the U.S., as well as near majority control of dairy and grocery retailers themselves. The same corporations running factory farms who are responsible for the most destructive practices on the environment, labor, public health and rural economies are also the enemy of the independent family farmers and ranchers. There are farmers and ranchers who understand the need to build coalition and common cause with other stakeholders in this fight. I heard said at the meetings, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

Exhibit one, a keynote slot was given to Wayne Pacelle, president of the Humane Society of the United States – a very effective organization that works to put an end to abuse of livestock and has proven its muscle with wins against battery cages for hens in California, and created a domino effect of retail chains pledging to phase out pork produced with gestation crates. I don’t have to tell you how much historic animosity and distrust there is between the animal welfare organizations and ranchers. Well, these guys have built a bridge, and they are anxious to do the same with the so-called “good food movement” and consumer advocacy groups as well. While there was less mention of environmental organizations, there are opportunities for bridge-building if groups are thoughtful about language, messengers and approach.

Common ground

Working to support the vestiges of independent family agriculture in the fight for fair and competitive marketplace for producers and consumers could be a high-reward strategy for engaging a very important constituency in changing practices that will have a positive impact on the climate. For example, transitioning farmers from traditional feedlot cattle operations with expensive inputs in feed, antibiotics, and low return in the corporate marketplace to grass-based operations with low input, reduced fossil fuel use, reduced air and water pollution and greenhouse gas impact, and higher returns for farmers and rural economies is a win-win.

We don’t need to walk through the front door with farmers hoping to get them on the same page about climate change. Rather, we should work to foster peer-to-peer communication, and local, trusted messengers to help incentivize producers towards better practices, including climate preparedness. A no-till cooperative of wheat growers in the Pacific Northwest for example has grown from just a few farms to include 43 growers as word of mouth spread about the benefits of this change in production practice.

Climate advocates shouldn’t try to convince farmers that change is necessary to address a problem that most may never agree is a problem – even as they struggle for survival and liquidate their herds in the middle of drought. What we can do is support messengers and solutions that meet the particular needs of this unique and important set of stakeholders.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.