Half Of Great Barrier Reef Lost In Past 3 Decades

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is a glittering gem — the world’s largest coral reef ecosystem — chock-full of diverse marine life. But new research shows it is also in steep decline, with half of the reef vanishing in the past 27 years.

Katharina Fabricius, a coral reef ecologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and study co-author, told LiveScience that she has been diving and working on the reef since 1988 — and has watched the decline. “I hear of the changes anecdotally, but this is the first long-term look at the overall status of the reef. There are still a lot of fish, and you can see giant clams, but not the same color and diversity as in the past.”

To get their data, Fabricius and her colleagues surveyed 214 different reefs around the Great Barrier Reef, compiling information from 2,258 surveys to determine the rate of decline between 1985 and 2012. They estimated the coral cover, or the amount of the seafloor covered with living coral.

Horseshoe reef before crown-of-thorns invasion.

That overall 50-percent decline, they estimate, is a yearly loss of about 3.4 percent of the reef. [Photos of Great Barrier Reef Through Time]

They did find some local differences, with the relatively pristine northern region showing no decline over the past two decades.

Cyclones and starfish

The reef’s decline, detailed this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can be chalked up to several factors, they found. The biggest factors are smashing from tropical cyclones, crown-of-thorns starfish that eat coral and are boosted by nutrient runoff from agriculture, and coral bleaching from high-temperatures, which are rising due to climate change. (Coral bleaching happens when ocean temperatures rise and cause the corals to expel their zooxanthellae — the tiny photosynthetic algae that live in the coral’s tissues.)

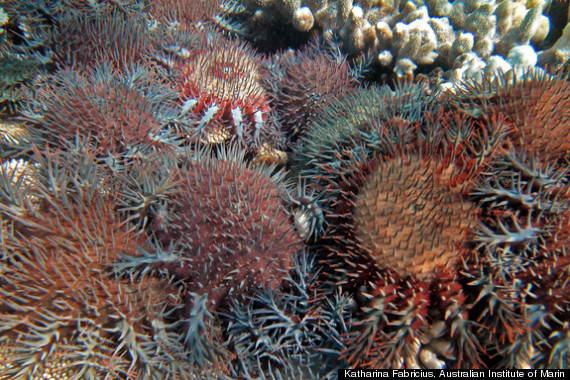

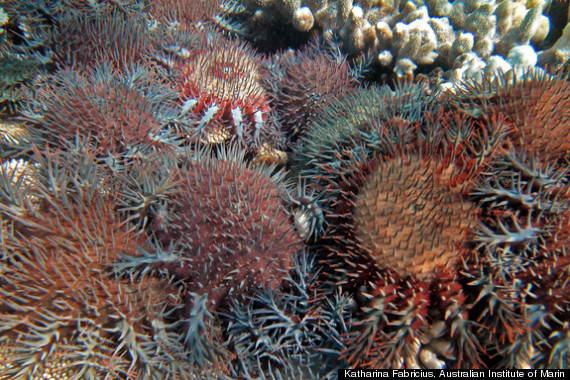

Horseshoe reef after crown-of-thorns invasion.

Other coral experts say the precipitous decline matches what they have found. “This is a really grim wake-up call,” said John Bruno, a biologist at UNC Chapel Hill. “The GBR [Great Barrier Reef], which only 10 years ago was considered the world’s most pristine and resilient coral reef is clearly not better off and no less threatened than any other reef. I am bullish on the long-term survival of reefs, but science like this is challenging that outlook.”

Saving the reef

As for what can be done to save the reef, or what’s left of it, some say reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is key. “International efforts to cap and reduce CO2 emissions are equally critical and must occur at the same time as cleaning up local impacts,” said Les Kaufman, a biologist at Boston University who is part of an international consensus statement on climate change and coral reefs.

Fabricius says not much can be done in the short term about the climate-change-driven frequency of cyclones — five category 5 storms in the past seven years have pounded the reefs — or high temperatures. However, there are efforts in place to stem the damage from starfish, which can grow up to 3 feet (0.9 meters) in diameter and sport long venomous spines and 21 arms. Young starfish feed on coral-making algae, and leave behind the coral’s skeleton.

Population outbreaks of the coral eating starfish Acanthaster planci have been responsible for 42% of the over 50% decline in coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef between 1985 and 2012.

One project encourages farmers to adopt practices that limit the amount of nutrient-rich runoff draining into reef areas. Another would allow tour operators to manually remove starfish from tourist areas, which Fabricius admits isn’t a solution, just a temporary fix.

Another option is to examine ways of harnessing natural starfish diseases that typically keep starfish numbers low. “Starfish normally are rare,” Fabricius said. “We want to help Mother Nature keep them rare.” The research shows that the reef could rebuild itself in 20-30 years despite the cyclones and bleaching, if the starfish population died back.

The experts agree that doing nothing is not an option at this point. “The problem is entirely soluble, and coral reefs can be saved through concerted effort over this and the following two or three generations,” said Kaufman. “There is absolutely no excuse for failure to do this, and if we do fail our generation will forever be remembered for unimaginable, unforgivable stupidity and sloth.”

Katharina Fabricius, a coral reef ecologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and study co-author, told LiveScience that she has been diving and working on the reef since 1988 — and has watched the decline. “I hear of the changes anecdotally, but this is the first long-term look at the overall status of the reef. There are still a lot of fish, and you can see giant clams, but not the same color and diversity as in the past.”

To get their data, Fabricius and her colleagues surveyed 214 different reefs around the Great Barrier Reef, compiling information from 2,258 surveys to determine the rate of decline between 1985 and 2012. They estimated the coral cover, or the amount of the seafloor covered with living coral.

Horseshoe reef before crown-of-thorns invasion.

That overall 50-percent decline, they estimate, is a yearly loss of about 3.4 percent of the reef. [Photos of Great Barrier Reef Through Time]

They did find some local differences, with the relatively pristine northern region showing no decline over the past two decades.

Cyclones and starfish

The reef’s decline, detailed this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can be chalked up to several factors, they found. The biggest factors are smashing from tropical cyclones, crown-of-thorns starfish that eat coral and are boosted by nutrient runoff from agriculture, and coral bleaching from high-temperatures, which are rising due to climate change. (Coral bleaching happens when ocean temperatures rise and cause the corals to expel their zooxanthellae — the tiny photosynthetic algae that live in the coral’s tissues.)

Horseshoe reef after crown-of-thorns invasion.

Other coral experts say the precipitous decline matches what they have found. “This is a really grim wake-up call,” said John Bruno, a biologist at UNC Chapel Hill. “The GBR [Great Barrier Reef], which only 10 years ago was considered the world’s most pristine and resilient coral reef is clearly not better off and no less threatened than any other reef. I am bullish on the long-term survival of reefs, but science like this is challenging that outlook.”

Saving the reef

As for what can be done to save the reef, or what’s left of it, some say reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is key. “International efforts to cap and reduce CO2 emissions are equally critical and must occur at the same time as cleaning up local impacts,” said Les Kaufman, a biologist at Boston University who is part of an international consensus statement on climate change and coral reefs.

Fabricius says not much can be done in the short term about the climate-change-driven frequency of cyclones — five category 5 storms in the past seven years have pounded the reefs — or high temperatures. However, there are efforts in place to stem the damage from starfish, which can grow up to 3 feet (0.9 meters) in diameter and sport long venomous spines and 21 arms. Young starfish feed on coral-making algae, and leave behind the coral’s skeleton.

Population outbreaks of the coral eating starfish Acanthaster planci have been responsible for 42% of the over 50% decline in coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef between 1985 and 2012.

One project encourages farmers to adopt practices that limit the amount of nutrient-rich runoff draining into reef areas. Another would allow tour operators to manually remove starfish from tourist areas, which Fabricius admits isn’t a solution, just a temporary fix.

Another option is to examine ways of harnessing natural starfish diseases that typically keep starfish numbers low. “Starfish normally are rare,” Fabricius said. “We want to help Mother Nature keep them rare.” The research shows that the reef could rebuild itself in 20-30 years despite the cyclones and bleaching, if the starfish population died back.

The experts agree that doing nothing is not an option at this point. “The problem is entirely soluble, and coral reefs can be saved through concerted effort over this and the following two or three generations,” said Kaufman. “There is absolutely no excuse for failure to do this, and if we do fail our generation will forever be remembered for unimaginable, unforgivable stupidity and sloth.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.