Bill McKibben Wrestles The Octopus In The Room

Bill McKibben, the environmental author-turned-activist, knows his movement is troubled. But he’s committed to protecting the environment, so he trudges forward, battling setbacks, death threats and what he sees as his primary enemy: the fossil fuel industry. In 2008, he launched the grassroots campaign 350.org, and last year played a pivotal role in raising public opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline project. But he’s concerned he’s fighting a losing battle against climate change.

Bill McKibben, the environmental author-turned-activist, knows his movement is troubled. But he’s committed to protecting the environment, so he trudges forward, battling setbacks, death threats and what he sees as his primary enemy: the fossil fuel industry. In 2008, he launched the grassroots campaign 350.org, and last year played a pivotal role in raising public opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline project. But he’s concerned he’s fighting a losing battle against climate change.You were arrested during the Keystone XL pipeline protests. Is civil disobedience necessary for a campaign to be successful?

It’s one tool in the toolkit, I guess—and not the one you usually reach for first. But it is a way to demonstrate the moral urgency of questions. It needs, I think, to be totally nonviolent and dignified—the Keystone protests, which were the largest civil disobedience actions in 30 years in this country, were a good example. We told people: come in a necktie or a dress. Because we need to demonstrate who the radicals are in this fight. They’re not us.

You’ve said efforts to combat climate change have largely failed. What needs to happen for progress to be made?

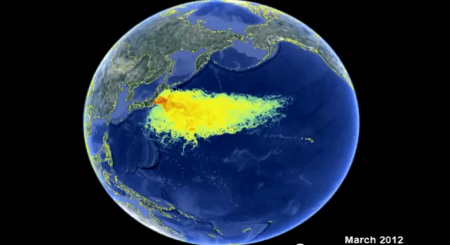

At this point the great obstacle is the political power of the fossil fuel industry. As I showed in that recent Rolling Stone piece, their business plan calls for them to burn 5 times the amount of carbon that even conservative governments think is safe—in order to do that, they have to warp our political systems, which they do with massive donations and lobbying. At 350.org, the night after the election, we’re going to mount a massive effort to try and focus on their irresponsibility—we hope we can spark a movement something like the one that led campuses and communities to divest from companies that did business in South Africa.

What does a clean energy future look like? Could fracking be part of a bridge to it?

Given the math of climate change, fracking’s no help. We don’t need a bridge—we need to make the leap to renewable energy. Germany’s done more than anyone else in the last decade—they’re already at the 25 percent mark, and one day in June they generated more than half the power they used with solar panels within their borders. (And remember that Munich is north of Montreal!) We have the technology; what we need is the political will.

Given rising CO2 emissions and more troublesome numbers, do you ever want to give up?

Some days, sure. But there are so many good people around the world engaged in this fight, many of them in places that have done nothing to contribute to this problem. As long as they’re willing to fight, so am I.

How do you reduce your own carbon footprint, and what do you tell your daughter about the troubling world her generation may face?

The year we built our house, it got a prize as the most energy efficient in Vermont. I drove the first Hydrid Honda Civic in the state (and still do); I spent a year feeding my family nothing that wasn’t grown in our valley and am still a committed locavore. There are solar panels all over the roof, and on a big stalk in the yard. But—I don’t try to fool myself that this is changing the world—and in fact, one organizing trip on an airplane negates it. But I take those trips because the only real hope is serious political change. My daughter is 19, and couldn’t be smarter and more aware; I don’t tell her stuff, she tells me stuff.

With so many issues to focus on, how do you allocate your time?

I think it’s become clear the real battle is with the fossil fuel industry. We need to fight their worst projects—tarsands pipelines, coal export terminals, mountaintop removal, fracking. But we also, maybe even more, need to figure out how to go to the heart—take on the octopus itself, not just its tentacles.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.