Batteries got cheaper in 2021. So how close are we to EVs that cost less than gasoline vehicles?

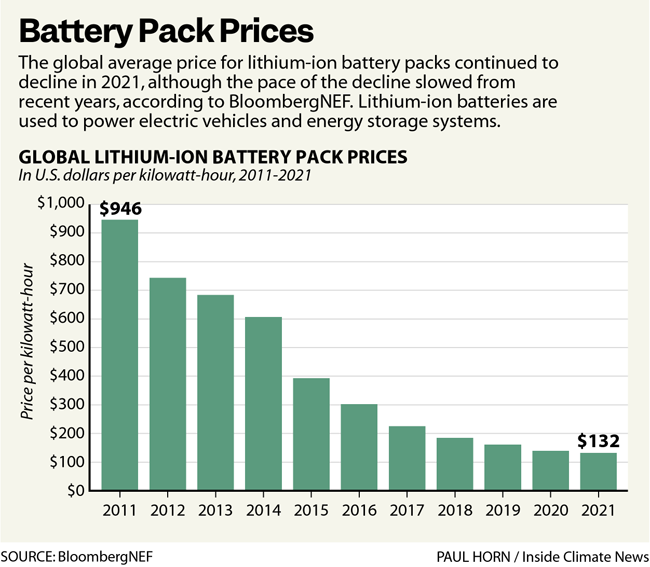

The price of the batteries that power electric vehicles has fallen by about 90 percent since 2010, a continuing trend that will soon make EVs less expensive than gasoline vehicles.

The price of the batteries that power electric vehicles has fallen by about 90 percent since 2010, a continuing trend that will soon make EVs less expensive than gasoline vehicles.

This week, with battery pricing figures for 2021 now available, I wanted to get a better idea of what the near future will look like.

First, the numbers: The average price of lithium-ion battery packs fell to $132 per kilowatt-hour in 2021, down 6 percent from $140 per kilowatt-hour the previous year, according to the annual battery price survey from BloombergNEF. The new average is a step closer to the benchmark of $100 per kilowatt-hour, which researchers say is the approximate point where EVs will cost about the same as gasoline-powered vehicles.

While prices declined in 2021, the decrease was not as much as BloombergNEF had projected, because of increases in costs for key materials like lithium, cobalt and nickel. The rising costs of materials are leading the research firm’s analysts to say that battery prices appear to be poised for a slight increase next year. But the same analysts expect that battery prices will soon resume their decline, as EV production ramps up and the companies find savings in economies of scale.

Batteries should hit an average of $100 per kilowatt-hour as soon as 2024, according to BloombergNEF. However, if automakers do not find ways to mitigate the rising costs of materials, the point when prices reach $100 could be pushed back by up to two years, the battery price report says.

The $100 per kilowatt-hour benchmark is now close enough that car buyers should understand what it means and what it doesn’t. For example, does this battery price mean that I can walk into any dealership and get an EV for the same price or less than a gasoline vehicle with equivalent features? No.

David Reichmuth, a senior engineer for the clean transportation program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told me that consumers should view the $100 benchmark as the high end of a range of battery prices in which EVs begin to achieve cost parity with gasoline vehicles. That range is from about $60 to $100 per kilowatt-hour.

“It’s not going to be a light switch kind of thing,” he said about EVs becoming the cheaper option. The shift will take years to manifest across manufacturers and vehicle types.

Once prices get to about $60 per kilowatt-hour, which forecasters say could be coming in about 2030, then EVs should be less expensive than gasoline models across just about every vehicle segment, including pickups and SUVs.

But it’s important to define the terms when comparing prices between EVs and gasoline vehicles. So far, I’ve been describing this in terms of the purchase price of a new vehicle, which is a simple calculation.

The more complicated calculation is the “total cost of ownership,” including fuel, insurance, maintenance and depreciation. When looked at this way, EVs often do better than gasoline vehicles, because of savings on fuel and maintenance.

The federal Department of Energy offers a calculator to help consumers estimate the cost differences, including between gasoline and electricity. This tool shows, for example, that an all-electric Chevrolet Bolt, a subcompact hatchback, costs about $15,000 more to purchase than the Chevrolet Trax, a subcompact SUV that runs on gasoline, not counting tax credits for the EV. But the Bolt costs about $700 less per year to operate.

Car & Driver magazine did a comparison last year of the cost of ownership and found that the all-electric Mini Electric cost about the same as its gasoline equivalent over three years, while the all-electric Hyundai Kona was more expensive than its gasoline equivalent. The figures did not include state and local tax credits.

As battery prices decrease, the gap in the purchase prices should continue to shrink, while EVs continue to have lower costs to operate. Tax credits, like the $7,500 per-vehicle credit being considered in Congress as part of the Build Back Better bill, also are major factors in EVs reaching cost parity with gasoline vehicles.

While we don’t know exactly when EVs will cost less than gasoline models, analysts tell me there is no doubt that this point is coming.

“Everything at some point will reach cost parity,” said Michael Nicholas, a researcher in the electric vehicle program at the International Council on Clean Transportation, a nonprofit research group. “Everything,” means all types of vehicles, from subcompact cars to full-size SUVs.

Nicholas was co-author of a 2019 paper that sought to predict the changes in EV prices from that year to 2030 for various types of vehicles. The results illustrate some of the points Reichmuth was making about how, as the years pass, EV prices will fall to be about the same as gasoline vehicles, and then EVs will be cheaper.

As EV prices decrease, Nicholas expects to see a virtuous cycle in which price declines will contribute to rising sales of EVs. As sales rise, automakers will increase EV production to meet demand, which will lead to economies of scale and additional reductions in prices.

Electric vehicle market share is rising, but still small, making up 2.6 percent of all new light duty cars and trucks sold in the United States from January to September of this year, up from 1.6 percent in the same period in 2020.

The long-term goal for automakers and for clean transportation researchers is to increase battery range while decreasing battery prices and charging times to the point that owning an EV is more desirable than owning a gasoline vehicle.

The perpetual caveat when talking about EVs is that they are not a cure-all for the problem of transportation emissions. EVs have emissions from manufacturing and from the production of electricity, and the vehicles contribute to the need for more roads with pavement, which has its own substantial carbon footprint. Many EVs are extremely heavy, which increases emissions from manufacturing and damages roads. Even the most enthusiastic EV promoters believe government officials also need to encourage walking, biking and mass transit.

That said, the growth of EV market share is an encouraging sign about the progress of the transition to clean energy. And it’s a tangible sign, visible in the many new vehicles on the road that do not have tailpipes.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.