Antarctic Peninsula Warms Rapidly

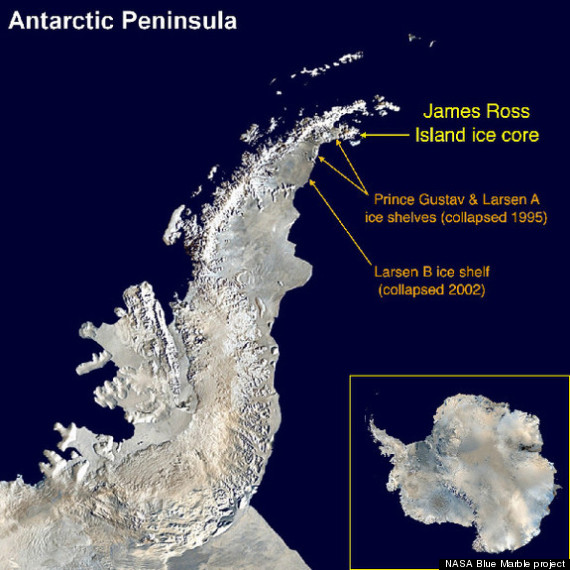

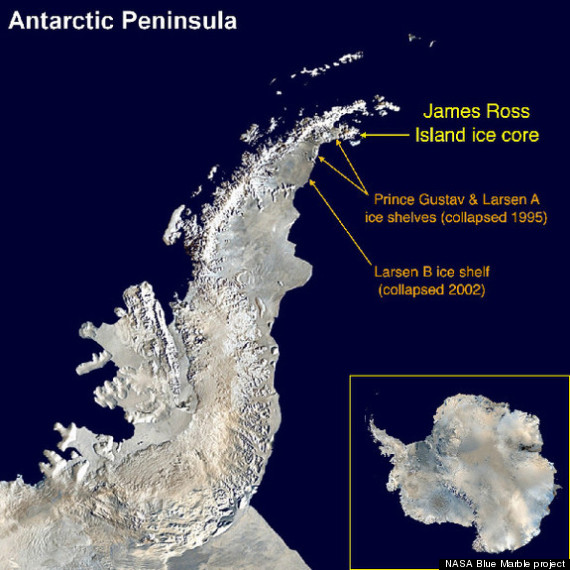

The Antarctic Peninsula, which juts out about 1,000 miles (1,610 kilometers) from the western flank of the frozen continent, is one of the fastest warming places on Earth.

In the past 50 years, the air temperature has increased by about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). While this rate of warming is highly unusual, it is not unprecedented, indicates a new study.

The rapid, modern warming is bringing the peninsula’s temperatures close to the warmth that followed the end of the last ice age, lead researcher Richard Mulvaney, a paleoclimatologist with the British Antarctic Survey, told LiveScience.

“We are now approaching the temperatures last seen 12,000 years ago,” he wrote in an email.

Mulvaney and colleagues predict continued warming will have serious implications for the ice shelves that jut from the peninsula over the ocean. In recent decades, ice shelves at the northern part have begun collapsing into the sea. Continued warming puts ice shelves further south at risk, they say.

Researchers load boxes of ice cores onto an airplane. The ice cores, taken from James Ross Island near the Antarctic Peninsula, were used to reconstruct temperature history of the region and better understand the recent collapse of ice shelves.

Back in time

To look back at millennia of temperature history for the peninsula, a research team extracted a 1,200-foot (364-meter) ice core from the summit of an island mountain near the northern tip of the peninsula.

Chemical clues in the sections of ice enabled researchers to reconstruct a record of temperature changes going back about 15,000 years, to a time when the last ice age was coming to an end.

Twice before in the past 2,000 years — around A.D. 400 and A.D. 1500 — the rate of warming has approached the modern one, Mulvaney said. The current warming trend began about 600 years ago, accelerating in the past 50 to 100 years, bringing the peninsula close to its post ice-age highs.

Warmth means melt

Warming isn’t just important for its own sake. While the thick layers of ice that extend from the frozen land have been stable for thousands of years, in the last 30 years rapid collapses, in which the ice shelves disintegrate into the sea, have begun, according to the U.S. Snow and Ice Data Center. [Antarctic Album: An Expedition Into Iceberg Alley]

In 1995, the northernmost portion of the Larsen Ice Shelf, about 770 square miles (2,000 square kilometers) collapsed, forming small icebergs. After retreating for some time, the nearby Prince Gustav Ice Shelf collapsed the same year.

Scientists have wondered if the loss of ice shelves and rising temperatures on the Antarctic Peninsula are the result of natural cycles or if humans’ alterations to the environment, including the ozone hole of Antarctica, are responsible. The results of the study don’t provide an answer to this question, but they do offer insight into the pre-Industrial temperature history and how it related to the state of the region’s ice shelves.

Reconstructing temperature from ice

Using the ice core, Mulvaney and his colleagues were able to look far back into the temperature history of the region, and compare that with records for the collapsed ice shelves, drawn from the marine sediments deposited below them.

To reconstruct the record of temperature, they looked at the ratio of heavier to lighter versions of hydrogen in the ice core from James Ross Island. Warmer temperatures allow for the incorporation of more heavy atoms, Mulvaney explained.

Their reconstruction revealed that after the last ice age ended 12,000 years ago, the climate became slightly warmer than it is today. After being stable near modern levels for millennia, a cooling trend, which included some warming spikes, began about 2,500 years ago, ending about 600 years ago. During this time, the ice shelves along the northern peninsula re-established themselves.

Between 100 and 50 years ago, this warming trend accelerated, taking the peninsula toward temperatures last seen 12,000 years ago, Mulvaney told LiveScience.

“This means some of those ice shelves farther south are starting to look vulnerable,” he said.

The loss of more ice shelves has implications for sea level. The ice shelves themselves don’t cause sea level to rise when they disintegrate, but in their absence, ice from the continent flows more quickly into the ocean, contributing to rising sea levels.

“The Antarctic Peninsula is small, it’s not adding a lot to sea-level rise. It’s more symptomatic of the changes taking place in Antarctica,” Mulvaney said.

Observations from a number of Antarctic ice shelves elsewhere show signs of the thinning responsible for the collapse of the northernmost ice shelves as well as the Wilkins Ice Shelf on the west side of the peninsula, according to Mulvaney.

In the past 50 years, the air temperature has increased by about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius). While this rate of warming is highly unusual, it is not unprecedented, indicates a new study.

The rapid, modern warming is bringing the peninsula’s temperatures close to the warmth that followed the end of the last ice age, lead researcher Richard Mulvaney, a paleoclimatologist with the British Antarctic Survey, told LiveScience.

“We are now approaching the temperatures last seen 12,000 years ago,” he wrote in an email.

Mulvaney and colleagues predict continued warming will have serious implications for the ice shelves that jut from the peninsula over the ocean. In recent decades, ice shelves at the northern part have begun collapsing into the sea. Continued warming puts ice shelves further south at risk, they say.

Researchers load boxes of ice cores onto an airplane. The ice cores, taken from James Ross Island near the Antarctic Peninsula, were used to reconstruct temperature history of the region and better understand the recent collapse of ice shelves.

Back in time

To look back at millennia of temperature history for the peninsula, a research team extracted a 1,200-foot (364-meter) ice core from the summit of an island mountain near the northern tip of the peninsula.

Chemical clues in the sections of ice enabled researchers to reconstruct a record of temperature changes going back about 15,000 years, to a time when the last ice age was coming to an end.

Twice before in the past 2,000 years — around A.D. 400 and A.D. 1500 — the rate of warming has approached the modern one, Mulvaney said. The current warming trend began about 600 years ago, accelerating in the past 50 to 100 years, bringing the peninsula close to its post ice-age highs.

Warmth means melt

Warming isn’t just important for its own sake. While the thick layers of ice that extend from the frozen land have been stable for thousands of years, in the last 30 years rapid collapses, in which the ice shelves disintegrate into the sea, have begun, according to the U.S. Snow and Ice Data Center. [Antarctic Album: An Expedition Into Iceberg Alley]

In 1995, the northernmost portion of the Larsen Ice Shelf, about 770 square miles (2,000 square kilometers) collapsed, forming small icebergs. After retreating for some time, the nearby Prince Gustav Ice Shelf collapsed the same year.

Scientists have wondered if the loss of ice shelves and rising temperatures on the Antarctic Peninsula are the result of natural cycles or if humans’ alterations to the environment, including the ozone hole of Antarctica, are responsible. The results of the study don’t provide an answer to this question, but they do offer insight into the pre-Industrial temperature history and how it related to the state of the region’s ice shelves.

Reconstructing temperature from ice

Using the ice core, Mulvaney and his colleagues were able to look far back into the temperature history of the region, and compare that with records for the collapsed ice shelves, drawn from the marine sediments deposited below them.

To reconstruct the record of temperature, they looked at the ratio of heavier to lighter versions of hydrogen in the ice core from James Ross Island. Warmer temperatures allow for the incorporation of more heavy atoms, Mulvaney explained.

Their reconstruction revealed that after the last ice age ended 12,000 years ago, the climate became slightly warmer than it is today. After being stable near modern levels for millennia, a cooling trend, which included some warming spikes, began about 2,500 years ago, ending about 600 years ago. During this time, the ice shelves along the northern peninsula re-established themselves.

Between 100 and 50 years ago, this warming trend accelerated, taking the peninsula toward temperatures last seen 12,000 years ago, Mulvaney told LiveScience.

“This means some of those ice shelves farther south are starting to look vulnerable,” he said.

The loss of more ice shelves has implications for sea level. The ice shelves themselves don’t cause sea level to rise when they disintegrate, but in their absence, ice from the continent flows more quickly into the ocean, contributing to rising sea levels.

“The Antarctic Peninsula is small, it’s not adding a lot to sea-level rise. It’s more symptomatic of the changes taking place in Antarctica,” Mulvaney said.

Observations from a number of Antarctic ice shelves elsewhere show signs of the thinning responsible for the collapse of the northernmost ice shelves as well as the Wilkins Ice Shelf on the west side of the peninsula, according to Mulvaney.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.