Why Germany is looking to Canada for its future hydrogen supply

One of the German government’s top officials came to Ottawa this month with a message about his country’s hunger for Canadian hydrogen.

One of the German government’s top officials came to Ottawa this month with a message about his country’s hunger for Canadian hydrogen.

Jorg Kukies was here to follow up on a March meeting between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Chancellor Olaf Schulz, whom he serves as chief economic adviser. And when he sat down with The Globe and Mail, he suggested that the potential for Canada to provide the low-carbon energy source to Germany is so obvious, “it’s like Economics 101.”

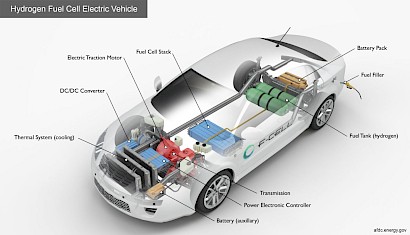

Hydrogen is where Germany is pinning hopes for both long-term energy security – an imperative brought into sharp relief by the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and transition to a greener economy. It’s seen as a solution for the energy needs of its heavy manufacturing industries, as well as commercial transportation and potentially building heating.

Germany won’t be able to produce nearly enough on its own, and is eyeing what it sees as a potentially abundant Canadian supply.

But straightforward though the potential mutual benefits of that trade relationship may be, Canada’s hydrogen calculus is more complex. Germany’s bullishness is adding to pressure to rapidly place bets on an emerging global market that is evolving in highly unpredictable ways.

There is lots of hype about hydrogen both from countries (such as Japan and South Korea) that want to import it for decarbonizing their large industries, and from competitors to export it (Australia, Saudi Arabia, Chile). But there is almost no actual trade so far.

“There’s so much uncertainty around the speed of the different potential suppliers,” Mr. Kukies acknowledged. “Nobody has the package to sell to anyone yet.”

That leaves Canada trying to figure out how quickly it must move to avoid missing the boat, and how much risk there is of aggressive investments not panning out. There are also domestic challenges to navigate – including how to accelerate development of infrastructure that could get hydrogen to international markets, without compromising environmental and ethical standards that are supposed to be a competitive advantage.

The onus on Ottawa to resolve these questions is coming from more than just Germany.

The Australian mining giant Fortescue Future Industries is trying to reposition itself as the world’s leading provider of so-called green hydrogen, which involves splitting the element from water using renewable electricity sources, and is exploring a range of potential production sites in Canada while lobbying for government backing.

Green hydrogen is where Mr. Kukies sees the really obvious trade potential with Canada. “The medium-term fascinating project is to exploit to mutual benefit the fact that our countries are as diametrically opposed to each other in sheer geography and population density as you could imagine,” he said. He meant that unlike Germany, Canada has the ability to leverage excess hydrogen production from wind, solar and hydroelectric power.

Meanwhile, many oil and gas companies currently operating in Western Canada want to pivot to blue hydrogen production, in which the element is produced from fossil fuels using a process called steam methane reforming, with carbon-capture technology used to minimize emissions. Those aims have been bolstered by a new federal carbon-capture tax credit for carbon capture, but companies are looking for more certainty that their investments would find a market.

And provinces have been rolling out hydrogen strategies with varying levels of ambition and detail, which likely require greater federal backing to get off the ground.

In an interview following Mr. Kukies’s visit, Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson said that his ministry is working on a “more granular road map” for hydrogen than the national strategy it released in 2020, which was mostly aspirational.

Mr. Wilkinson also gave some indication of how he sees an export market taking shape early on – pointing to the potential to use existing natural-gas infrastructure, including pipelines to Atlantic Canada, to get blue hydrogen to Europe.

He suggested that natural-gas export capacity could even be expanded slightly, including through Atlantic ports, in light of Europe’s nearer-term need to replace Russian fossil-fuel supply. That could then be converted to hydrogen transport.

Mr. Kukies gave some credence to that prospect, noting that Germany intends to continue using natural gas as a bridge fuel while it transitions toward emissions-neutrality. And while prior to its current energy crisis Germany was unenthusiastic about blue hydrogen because of doubts about its environmental credibility, it now seems more open to it.

But if Canada does develop an export market for blue hydrogen produced from oil and gas in Alberta and other Western provinces, Europe is not the likeliest destination.

Given the geography, it would more economical to get that product to Pacific ports for shipment to Asian markets, where there will be equally strong demand. And there is less hesitation around blue hydrogen in Japan than in Germany.

Green hydrogen is a different story, not only because it better aligns with Germany’s environmental views, but also because it’s likelier to be produced in Quebec and Atlantic Canada, making it easier to get to Atlantic ports.

That prospect is getting more buzz in some provinces than others. Newfoundland and Labrador has recently been talking up its ability to become a major exporter, while Quebec has signalled that it would prefer to use the ample production potential from its hydroelectricity to meet domestic energy-transition needs.

But prioritizing domestic usage may not be at odds with long-term export hopes. In fact, many around the nascent sector point to it as a way to realize those ambitions.

There are plenty of willing hydrogen producers in this country, they say. The issue is that the market has not yet taken shape, even at home, enough to assuage fears of white elephants.

“If you can demonstrate hydrogen demand, the production will come, whether it’s blue hydrogen or green hydrogen,” said David Layzell, the energy systems architect for the non-profit Transition Accelerator. He thinks at least half of hydrogen funding should go toward increasing demand.

Mark Kirby, the president of the Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Association (CHFA), made a similar argument. His organization is calling for a major ramp-up of hydrogen hubs, in which governments work with the private sector to try to scale up hydrogen deployment in regions with local or nearby production capacity.

The main such effort in Canada so far is in the Edmonton area, where projects range from industrial power to fuel-cell trucks running between there and Calgary. The CHFA is calling for as many as 30 hubs by the end of this decade.

Mr. Wilkinson embraced those calls, although he envisions more like seven or eight hubs for starters. The idea is that the hydrogen economy will grow out from there, spurring enough production enough to meet more than just Canada’s needs.

But even if that model works, it won’t alleviate the need for some risk in planning trade routes, if Canada is serious about being a major global supplier.

Some larger hydrogen projects, which will take many years to develop, might not make financial sense unless there is an export market. And there is a particular need to develop or repurpose ports, pipelines and other means of getting hydrogen to market.

Canada is not known for its speed with that sort of infrastructure. Given the many things it would need to get right – including Indigenous partnership, and upholding environmental standards – advance work would need to start soon.

That has Ottawa trying to figure out how much assurance on hydrogen demand it can get from countries like Germany.

“We’re trying to figure out what they could do that would provide sufficient confidence for the proponents to be able to make the investment,” Mr. Wilkinson said. “Given where the markets are, it’s probably not firm, binding agreements. But there has to be some degree of commitment.”

Mr. Kukies was not here to provide that level of certainty. But he downplayed the risks.

“If the experts are right, there will be enough demand on the planet,” he said. “It’s hard to believe that it doesn’t work from a business perspective.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.