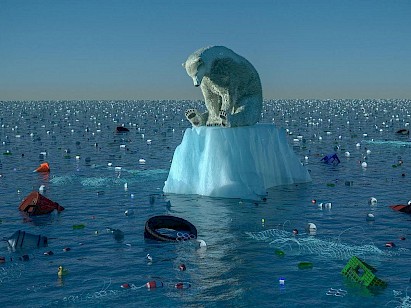

The world’s ‘plastic flood’ has reached the Arctic

“All spheres” of the Arctic, from seafloors to rivers to remote areas of ice and snow, are now littered with “high concentrations” of waste plastics, scientists have said – and the situation is worsening.

“All spheres” of the Arctic, from seafloors to rivers to remote areas of ice and snow, are now littered with “high concentrations” of waste plastics, scientists have said – and the situation is worsening.

Large quantities of plastic waste and microplastic particles are now being transported to the Arctic by oceans, rivers, shipping and air, according to the research team from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven, Germany.

The huge quantity of plastic entering the world’s oceans and eventually ending up in the most remote places not only directly impacts ecosystems, but it could also exacerbate the climate crisis in the Arctic, the scientists said.

This is because dark-coloured plastic particles could absorb more heat than snow and ice, and any suspended microplastics in the air could cause condensation – which then may cause additional rain, melting ice and snow.

The research team said the Arctic Ocean has become a major plastic repository. Despite making up one per cent of the total volume of the world’s oceans, it receives more than 10 per cent of the global discharge from the world’s rivers, which carry plastic into the ocean.

Today, virtually all marine organisms investigated, from plankton to sperm whales, come into contact with plastic debris and microplastics. And this applies to all areas of the world’s oceans, from tropical beaches to the deepest oceanic trenches.

“The Arctic is still assumed to be a largely untouched wilderness,” says AWI expert Dr Melanie Bergmann.

“In our review, which we jointly conducted with colleagues from Norway, Canada and the Netherlands, we show that this perception no longer reflects the reality.

“Our northernmost ecosystems are already particularly hard hit by climate change. This is now exacerbated by plastic pollution. And our own research has shown that the pollution continues to worsen.”

The researchers said their findings “paint a grim picture”. Although the Arctic is sparsely populated, in virtually all habitats – from beaches and the water column, to the seafloor – it shows a similar level of plastic pollution as densely populated regions around the globe.

As well as rivers flowing into the Arctic Ocean, the pollution also stems from ocean currents from the Atlantic and the North Sea, and from the North Pacific over the Bering Strait. Tiny microplastic particles are also carried northward by wind.

The plastics are then caught and swirled around the top of the globe. When seawater off the coast of Siberia freezes in the autumn, suspended microplastics become trapped in the ice. The Transpolar Drift current then transports the ice floes to Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard, where it melts in the summer, releasing its plastic cargo.

The scientists said some of the biggest local sources of pollution are municipal waste and wastewater from Arctic communities and plastic debris from ships, especially fishing vessels, whose nets and ropes pose a serious problem. Either intentionally dumped in the ocean or unintentionally lost, they account for a large share of the plastic debris in the European sector of the Arctic: on one beach on Svalbard, almost 100 per cent of the plastic mass washed ashore came from fisheries, according to an AWI study.

“Unfortunately, there are very few studies on the effects of the plastic on marine organisms in the Arctic,” said Dr Bergmann.

“But there is evidence that the consequences there are similar to those in better-studied regions: in the Arctic, too, many animals – polar bears, seals, reindeer and seabirds – become entangled in plastic and die.

“In the Arctic, too, unintentionally ingested microplastics likely lead to reduced growth and reproduction, to physiological stress and inflammations in the tissues of marine animals, and even runs in the blood of humans.”

Speaking about the potential feedback loop which plastic debris could cause, and thereby exacerbate the climate crisis, the team said research remains “particularly thin”.

“Here, there is an urgent need for further research,” said Dr Bergmann.

“Initial studies indicate that trapped microplastics change the characteristics of sea ice and snow.”

As well as absorbing heat and altering precipitation, the researchers said throughout their lifecycle, plastics are currently responsible for 4.5 per cent of global greenhouse-gas emissions.

“Our review shows that the levels of plastic pollution in the Arctic match those of other regions around the world. This concurs with model simulations that predict an additional accumulation zone in the Arctic,” said Dr Bergmann.

“But the consequences might be even more serious. As climate change progresses, the Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the world. Consequently, the plastic flood is hitting ecosystems that are already seriously strained.

“The resolution for a global plastic treaty, passed at the UN Environment Assembly this February, is an important first step. In the course of the negotiations over the next two years, effective, legally binding measures must be adopted, including reduction targets in plastic production.”

The team also called on European countries to slash their levels of plastic waste, and called for stronger controls on fishing gear entering oceans.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.