Scientists say 93 percent of the Great Barrier Reef now bleached.

The conclusions are in from a series of scientific surveys of the Great Barrier Reef bleaching event — an environmental assault on the largest coral ecosystem on Earth — and scientists aren’t holding back about how devastating they find them.

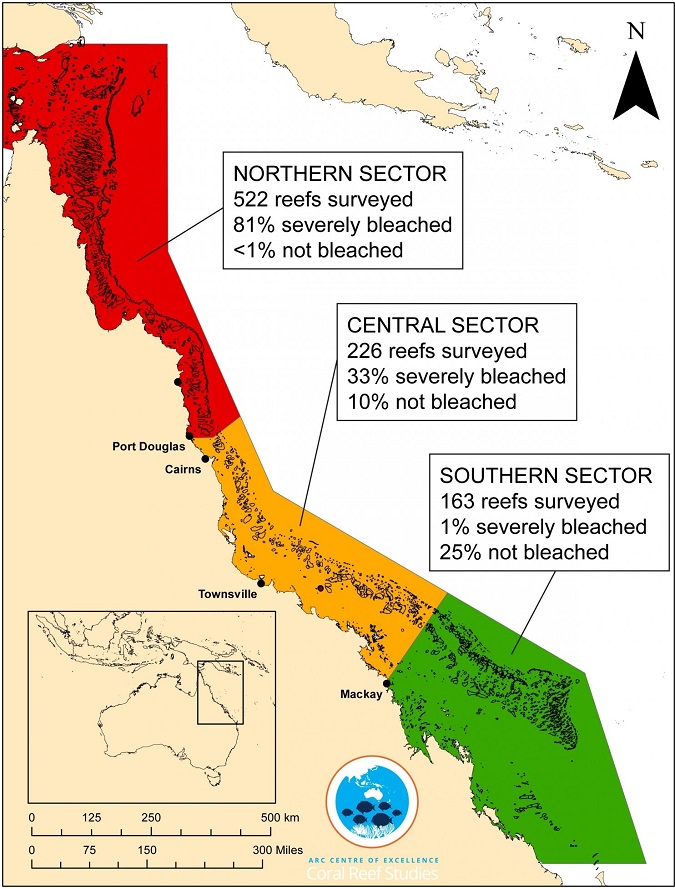

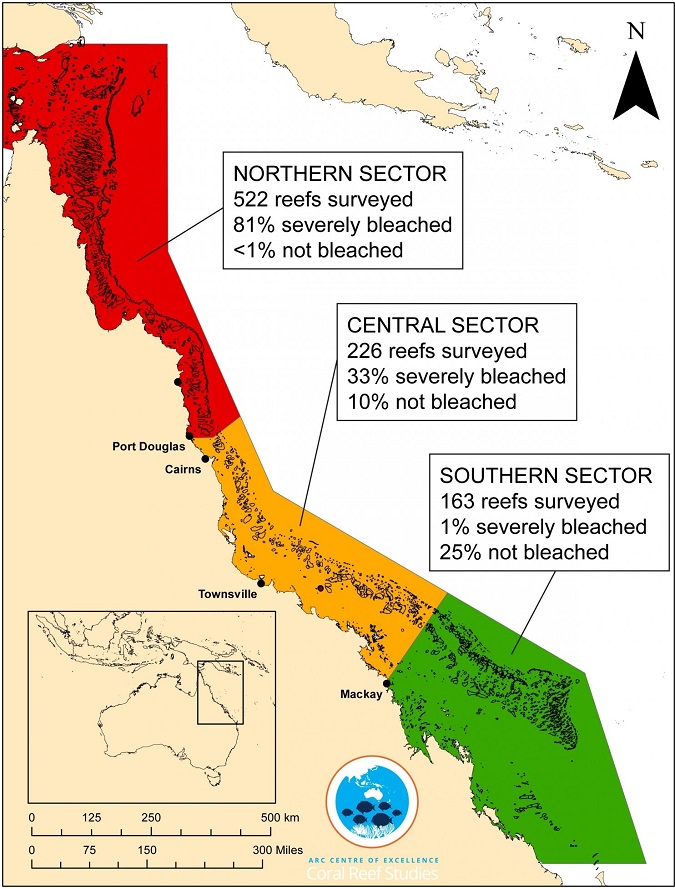

Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Task Force has surveyed 911 coral reefs by air, and found at least some bleaching on 93 percent of them. The amount of damage varies from severe to light, but the bleaching was the worst in the reef’s remote northern sector — where virtually no reefs escaped it.

“Between 60 and 100 percent of corals are severely bleached on 316 reefs, nearly all in the northern half of the Reef,” Prof. Terry Hughes, head of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, said in a statement to the news media. He led the research.

Severe bleaching means that corals could die, depending on how long they are subject to these conditions. The scientists also reported that based on diving surveys of the northern reef, they already are seeing nearly 50 percent coral death.

“The fact that the most severely affected regions are those that are remote and hence otherwise in good shape, means that a lot of prime reef is being devastated,” said Nancy Knowlton, Sant Chair for Marine Science at the Smithsonian Institution, in an email in response to the bleaching announcement. “One has to hope that these protected reefs are more resilient and better able to recover, but it will be a lengthy process even so.”

Knowlton added that Hughes, who led the research, is “NOT an alarmist.”

Here’s a map that the group released when announcing the results, showing clearly that bleaching hit the northern parts of the reef the worst:

Hughes tweeted the map above, writing, “I showed the results of aerial surveys of #bleaching on the #GreatBarrierReef to my students, And then we wept.”

“This is, by far, the worst bleaching they’ve seen on the Great Barrier Reef,” said Mark Eakin, head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch, which partners with the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce. “Our climate model-based Four Month Bleaching Outlook was predicting that severe bleaching was likely for the [Great Barrier Reef] back in December. Unfortunately, we were right and much of the reef has bleached, especially in the north.”

Responding to the news Wednesday, the Australian government’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority put out a statement from its chairman Russell Reichelt. “While the data is incomplete, it is clear there will be an impact on coral abundance because of bleaching-induced mortality, mainly in the far north,” the statement said in part.

Coral bleaching occurs when corals are stressed by unusually high water temperatures, or from other causes. When this happens, symbiotic algae, called zooxanthellae, leave the corals’ bodies. This changes their color to white and can also in effect starve them of nutrients. If bleaching continues for too long, corals die.

There already have been reports of mass coral death around the Pacific atoll of Kiribati this year — and widespread coral bleaching worldwide, a phenomenon that scientists attribute to a strong El Niño event surfing atop a general climate warming trend.

Tourism involving the Great Barrier Reef is worth $5 billion annually, and accounts for close to 70,000 jobs, according to the news release from the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce.

Recently, journalist Chelsea Harvey reported that some scientists think coral bleaching this extensive could be a sign of “dangerous” climate change caused by humans.

The 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, just after saying that countries should avoid such dangerous interference with the climate, adds that atmospheric greenhouse gas levels should be stabilized “within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change.”

Indeed, recent research suggests that Great Barrier Reef corals have a mechanism to protect them if waters warm up beyond normal, but then cool down again before a second warming that crosses the bleaching threshold. However, as oceans continue to warm, it found, that pattern will be less prevalent, meaning that corals will be less able to cope.

Past global coral bleaching events have occurred in 1998 and 2010. In 1998, scientists ultimately documented through much follow-up research that 16 percent of the world’s corals died in that event. The full toll of the current global bleaching event has not yet been determined.

Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Task Force has surveyed 911 coral reefs by air, and found at least some bleaching on 93 percent of them. The amount of damage varies from severe to light, but the bleaching was the worst in the reef’s remote northern sector — where virtually no reefs escaped it.

“Between 60 and 100 percent of corals are severely bleached on 316 reefs, nearly all in the northern half of the Reef,” Prof. Terry Hughes, head of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, said in a statement to the news media. He led the research.

Severe bleaching means that corals could die, depending on how long they are subject to these conditions. The scientists also reported that based on diving surveys of the northern reef, they already are seeing nearly 50 percent coral death.

“The fact that the most severely affected regions are those that are remote and hence otherwise in good shape, means that a lot of prime reef is being devastated,” said Nancy Knowlton, Sant Chair for Marine Science at the Smithsonian Institution, in an email in response to the bleaching announcement. “One has to hope that these protected reefs are more resilient and better able to recover, but it will be a lengthy process even so.”

Knowlton added that Hughes, who led the research, is “NOT an alarmist.”

Here’s a map that the group released when announcing the results, showing clearly that bleaching hit the northern parts of the reef the worst:

Hughes tweeted the map above, writing, “I showed the results of aerial surveys of #bleaching on the #GreatBarrierReef to my students, And then we wept.”

“This is, by far, the worst bleaching they’ve seen on the Great Barrier Reef,” said Mark Eakin, head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch, which partners with the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce. “Our climate model-based Four Month Bleaching Outlook was predicting that severe bleaching was likely for the [Great Barrier Reef] back in December. Unfortunately, we were right and much of the reef has bleached, especially in the north.”

Responding to the news Wednesday, the Australian government’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority put out a statement from its chairman Russell Reichelt. “While the data is incomplete, it is clear there will be an impact on coral abundance because of bleaching-induced mortality, mainly in the far north,” the statement said in part.

Coral bleaching occurs when corals are stressed by unusually high water temperatures, or from other causes. When this happens, symbiotic algae, called zooxanthellae, leave the corals’ bodies. This changes their color to white and can also in effect starve them of nutrients. If bleaching continues for too long, corals die.

There already have been reports of mass coral death around the Pacific atoll of Kiribati this year — and widespread coral bleaching worldwide, a phenomenon that scientists attribute to a strong El Niño event surfing atop a general climate warming trend.

Tourism involving the Great Barrier Reef is worth $5 billion annually, and accounts for close to 70,000 jobs, according to the news release from the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce.

Recently, journalist Chelsea Harvey reported that some scientists think coral bleaching this extensive could be a sign of “dangerous” climate change caused by humans.

The 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, just after saying that countries should avoid such dangerous interference with the climate, adds that atmospheric greenhouse gas levels should be stabilized “within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change.”

Indeed, recent research suggests that Great Barrier Reef corals have a mechanism to protect them if waters warm up beyond normal, but then cool down again before a second warming that crosses the bleaching threshold. However, as oceans continue to warm, it found, that pattern will be less prevalent, meaning that corals will be less able to cope.

Past global coral bleaching events have occurred in 1998 and 2010. In 1998, scientists ultimately documented through much follow-up research that 16 percent of the world’s corals died in that event. The full toll of the current global bleaching event has not yet been determined.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.