How the shipping industry can go from global polluter to carbon neutral

When the Wind Hunter, a new cargo ship in development in Japan, begins to sail, more than a dozen massive sails will help it run on wind power. Under the water, large turbines will generate electricity that can be used to make hydrogen on board, so whenever the wind stops blowing, the ship can run on zero-emissions hydrogen fuel.

When the Wind Hunter, a new cargo ship in development in Japan, begins to sail, more than a dozen massive sails will help it run on wind power. Under the water, large turbines will generate electricity that can be used to make hydrogen on board, so whenever the wind stops blowing, the ship can run on zero-emissions hydrogen fuel.

The ship is one of multiple new vessels aiming to transform the carbon footprint of shipping. The cargo ships that carry sneakers and cars and bananas across the ocean—sometimes making absurdly long journeys, taking fish caught in Scotland to China to be filleted, and then back to Scotland to be sold “locally”—are responsible for around 3% of global emissions. (If shipping was a country, it would be the sixth most polluting nation in the world, ahead of Germany.)

“We can’t solve climate change without cracking that,” says Dan Hubbell, shipping emissions campaign manager at the Ocean Conservancy. It’s harder to shift to renewable energy in a hulking cargo ship the length of three football fields (and that needs to travel thousands of miles) than it is to charge a car with electricity. The International Maritime Organization doesn’t plan to cut emissions in half until 2050. But the Ocean Conservancy and the nonprofit Pacific Environment recently published a report arguing that the industry can transition to zero emissions much more quickly. By 2035, with the right push from policy, every ship visiting a U.S. port could eliminate emissions, along with the trucks, trains, and cranes that work at the ports.

The industry has made fast transitions in the past; in the early 1900s, the report says, ships shifted from coal to diesel in a decade or two. Now, it’s likely that multiple technologies will be used at once. Some ships are likely to run on green hydrogen, which is made from splitting water with renewable electricity. Some will run on hydrogen fuel cells. Some smaller ships are beginning to test green ammonia, made from air, water, and renewable energy, which is easier to make and store than hydrogen. Electric batteries can’t store enough power for huge ships, but can provide auxiliary power. On some windy routes, smaller ships are returning to more traditional sails.

The industry has made fast transitions in the past; in the early 1900s, the report says, ships shifted from coal to diesel in a decade or two. Now, it’s likely that multiple technologies will be used at once. Some ships are likely to run on green hydrogen, which is made from splitting water with renewable electricity. Some will run on hydrogen fuel cells. Some smaller ships are beginning to test green ammonia, made from air, water, and renewable energy, which is easier to make and store than hydrogen. Electric batteries can’t store enough power for huge ships, but can provide auxiliary power. On some windy routes, smaller ships are returning to more traditional sails.

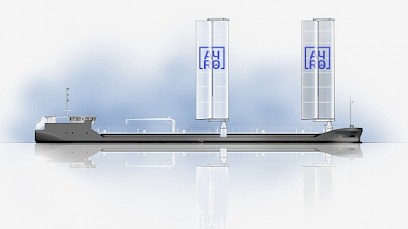

New fuels have challenges—they can’t store as much energy as the fossil fuels that ships rely on now, and at the moment, they’re more expensive. But other changes can help. Some ships are already adding sails for extra power, for example, and that’s something that could also happen on ships using alternative fuels. “This isn’t technology for the future,” says Gavin Allwright, secretary of the U.K.-based International Windship Association. “This is something that’s happening now.” Around a dozen ocean-going vessels now have “wind-assist” techology, and that number is expected to double this year and again in 2022. Cargill, the food and agriculture giant, is testing sails on its cargo ships and may expand that to its entire fleet of hundreds of ships.

If companies are willing to accept slightly slower shipments, that will also make it easier to use wind power and save fuel. Already, it’s common for shipments to speed to their destinations and then wait. A ship “could sit there for three weeks and not be unloaded,” says Allwright. “So you’ve rushed across the ocean, burned hundreds of tons of fuel per day, to sit there for a week waiting for a slot to come up to unload.” More customers now are trying to cut their own emissions, and accept different delivery times as they understand the climate benefits. Other tweaks to ship design and operation can also help reduce the amount of energy needed, including coatings and air bubbles that help the hull glide through water more smoothly.

While multiple types of energy will be used, wind has some advantages. “It’s delivered directly to the ship without any need for infrastructure,” Allwright says. “If you’ve got an alternative fuel, you’ve got to build the production facilities, the storage facilities, transport facilities, the bunkering facilities, but you also have to put storage onboard the vessel. We just go straight to the engine.” It’s also free, which is partly a challenge; investors want to see a continued return on investment after installation, so some companies making wind technology are exploring leasing models for their equipment.

While multiple types of energy will be used, wind has some advantages. “It’s delivered directly to the ship without any need for infrastructure,” Allwright says. “If you’ve got an alternative fuel, you’ve got to build the production facilities, the storage facilities, transport facilities, the bunkering facilities, but you also have to put storage onboard the vessel. We just go straight to the engine.” It’s also free, which is partly a challenge; investors want to see a continued return on investment after installation, so some companies making wind technology are exploring leasing models for their equipment.

Advocates want the U.S. to set a clean ship standard for every ship coming to American ports, with a 50% required cut in emissions by 2025, followed by 80% in 2030, and zero-emissions in 2035. The changes wouldn’t just have a climate benefit; air pollution in communities near ports is a major health problem. “This is also, among other things, an environmental justice issue,” says Hubbell. “Things like bunker fuel produce an inordinate amount of particulates, sulfur, and Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) pollution, all of which disproportionately, at least here in the United States, affect low-income communities and communities of color.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.