Europe′s water crisis: Rivers running dry

Amplified by human-induced climate change and water over-consumption, southern Europeans are feeling the consequences of more extreme heat waves and longer droughts.

Amplified by human-induced climate change and water over-consumption, southern Europeans are feeling the consequences of more extreme heat waves and longer droughts.

Now governments from Portugal to Italy are calling on citizens to limit water use to the bare minimum. But in some places, this is not enough.

While private consumption of water in the EU accounts for just 9% of total usage, around 60% is absorbed by agriculture.

“Droughts are one thing,” said Nihat Zal, a water expert at the European Environment Agency (EEA), which informs EU environment policy. “The other is how much water we take out of the system.”

Italy

The situation is probably most dramatic in northern Italy, where the region is suffering its drought.

More than 100 cities have been called on to limit water consumption as much as possible. On Monday, the Italian government declared a state of emergency for five regions until the end of the year. It plans to provide €36 million ($37 million) in the short term to combat the water crisis.

Due to months of drought and scarce winter rain, the water levels of the Dora Baltea and Po — the largest river in Italy — are eight times lower than usual.

Both rivers feed one of the most important agricultural regions in all of Europe, with 30% of production currently threatened by drought.

The irrigation authority in the northwestern region around the Sesia river has already ordered that fruit trees and poplars no longer be watered. The saved water will be used to irrigate the economically important rice crop.

The mayor of the city of Verona has announced that watering gardens and sports fields, washing cars and patios, and filling pools and swimming pools are now prohibited until the end of August to safeguard drinking water supplies. Vegetable gardens may only be watered at night.

Pisa is also resorting to rationing. As of this month, drinking water can only be used “for domestic use and personal hygiene.” Failure to comply will result in fines of up to 500 euros ($516).

In Milan, meanwhile, all decorative water fountains have been turned off.

The mayor of the small town of Castenaso wants to tackle the problem unconventionally: He has banned hairdressers and barbers from washing their customers’ hair twice. There are 10 hairdressers in the small town of 16,000 inhabitants, with the measure aiming to save thousands of liters of water per day.

Portugal

Portugal started to prepare for an extremely dry year back in winter. At the start of 2022, a lack of rainfall and low water levels in dams prompted the government to restrict the use of hydroelectric power plants to two hours per week. The goal is to guarantee the drinking water supply for Portugal’s 10 million inhabitants for at least two years.

What became apparent during the winter is all the more evident today. By the end of May, severe drought already prevailed in 97% of the country.

Due to the burning of coal, oil and gas, droughts that normally occur only once every 10 years have already become almost twice as likely in the Mediterranean region. Some regions are experiencing the worst dry season in a thousand years.

The association for agricultural irrigation in the towns of Silves, Lagoa and Portimao in southern Portugal has already activated an emergency plan under which 1,800 farms have to halve the irrigation of some crops.

Duarte Cordeiro, the Portuguese Minister for Environment and Climate Action, stated last week that despite current preparations, the country will have to live with restrictions and higher water costs in the future.

Duarte urged the business community to invest in water-saving measures, with Nihat Zal of the EEA seeing diverse opportunities to increase efficiency and reduce water wastage.

“On average, 25 % of fresh water is lost on the way from the water source, such as a river, to an industrial area,” Zal noted. Making water infrastructure more efficient will bring “huge potential savings.

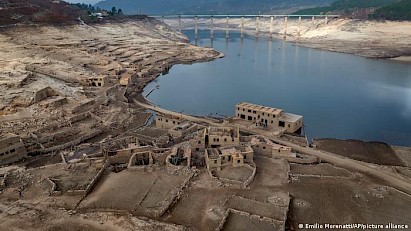

Spain

Spain is also extremely dry, with two-thirds of its total land area at risk of desertification. Once fertile soils are increasingly turning to sand, especially after the second driest winter since 1961, according to Spain’s meteorological bureau.

Spain is also extremely dry, with two-thirds of its total land area at risk of desertification. Once fertile soils are increasingly turning to sand, especially after the second driest winter since 1961, according to Spain’s meteorological bureau.

In the north, 17 localities were forced to take drastic measures as early as February, with the town of Campelles in Catalonia limiting running water to a few hours per day. For emergencies, the municipality deposited water buckets filled daily at five locations in the village.

In the small town of Vacarisses in the province of Barcelona, wells and groundwater pipes are also dry. Currently, people only have running water between six and ten in the morning, and from eight in the evening until midnight.

Spain is the third-largest producer of agricultural products in the EU. At least 70% of all fresh water is used for agriculture.

“The demand doesn’t stop growing,” said Juan Barea of Greenpeace Spain. “Instead of proposing policies that save water we are acting as if Spain had as much water as Norway or Finland. In reality, we are more on the level of North Africa.”

Although efficient drip irrigation is already used on a large proportion of agricultural land, at least one-fifth is still irrigated using unsustainable methods.

To better manage the water crises, it is necessary to move from crisis management and water rationing to instead think in the long term, says Zal of the EEA.

This means more efficiency in the use of water, forward-looking risk management and preparation for the next crisis. It also means “adapting to climate change at the individual level, at the local level, the government level, at all levels.”

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.