Canada's Chalk River Lab could contribute to solving world's nuclear waste problems

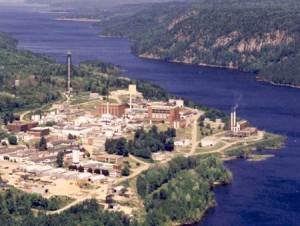

Change is in the air at Canada’s single-largest scientific outpost, located two hours northwest of Ottawa. That’s the history-rich home of Chalk River Laboratories, the heart of Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd.’s nuclear research division.

Change is in the air at Canada’s single-largest scientific outpost, located two hours northwest of Ottawa. That’s the history-rich home of Chalk River Laboratories, the heart of Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd.’s nuclear research division.You’ll recall that the Crown corporation’s commercial Candu reactor division was sold last year to Canadian engineering giant SNC Lavalin. That transaction represented the first phase of a larger AECL restructuring plan.

Under the second phase, which kicked off in February, the government is targeting the research division with an eye to getting more bang for the taxpayer buck, and bringing in a private-sector partner to make it happen.

Such public-private arrangements are well tested south of the border, where companies such as Lockheed Martin and Battelle operate major national labs in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy. The model seems to work well.

“The restructuring needs to determine the activities of interest to those stakeholders willing to invest in AECL, which would enable enhanced sharing of both benefits and risks while strengthening accountability,” according to a call for expressions of interest on Feb. 9.

Which areas of nuclear research should Chalk River focus on? What role, if any, does Canada want to play in the nuclear world? Those with ideas and suggestions have until April 2 to have their say.

One sensible view: focus on the waste.

The world has massive amounts of nuclear waste in the form of spent fuel from its existing fleet of nuclear plants. Even if we closed down all nuclear power plants tomorrow and stopped making nuclear weapons, we would still have a major waste management problem on our collective hands. The waste is here and it’s not going away anytime soon.

We can try to bury it at considerable expense and hope all will work out well for the next hundred thousand or so years, or we can purse ways of reusing that waste as a new source of fuel. Those are really the only two options.

The latter, if done right and responsibly, can solve many problems: It can reduce the volume of radioactive material that must go into long-term storage. It can reduce our need to mine new uranium and the associated environmental impacts of doing so. And it can give us more emission-free energy to wean us off fossil fuels and reduce global greenhouse-gas emissions.

Five years ago I wrote an article in this paper detailing a little-discussed feature of the Candu reactor design that allows it to use “waste” from rival light-water reactors (such as those used in the United States) as a fuel. It’s called the DUPIC process – standing for Direct Use of Spent Pressurized Water Reactor Fuel in Candus.

The Canadian government established a joint research program with the Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute in 1991 to investigate the approach, and both sides have demonstrated that it’s feasible.

“It’s progressed to the prototype stage,” said Jeremy Whitlock, a scientist at the Chalk River Lab. “We’ve made the fuel and we’ve put it into a reactor and it works fine.”

There are other, more expensive approaches that involve dissolving spent fuel in strong acids, carefully separating fissile material from the waste, turning it back into a solid material, and then processing back into useable fuel. This chemical processing is nasty, resulting in liquid wastes that need to be treated.

DUPIC doesn’t involve chemical separation, making it much simpler. The spent light-water reactor fuel is instead mechanically reshaped into fuel rods that fit into Candu reactors. And because plutonium is not chemically isolated and separated the approach is more proliferation resistant.

Politics aside, imagine co-locating DUPIC-configured Candu reactors at existing light-water nuclear facilities around the world, with their job being to generate additional emission-free electricity from stockpiles of spent fuel in short-term storage.

There are challenges. Handling and mechanically reprocessing spent fuel is tricky. This is hot stuff that’s highly radioactive. Special equipment, procedures and reactor modifications would be required to safely handle the material.

But it can be done, and arguably faster and more easily than trying to build fleets of waste-consuming fast breeder reactors, another technology worthy of pursuit but with longer time horizons. The Koreans, unfortunately, began losing interest in DUPIC a few year ago and have since turned their attention to the more ambitious fast breeder model.

Perhaps Chalk River should double-down on efforts? Perhaps SNC Lavalin, which now has exclusive commercial rights to DUPIC, could turn this into a new business opportunity?

Another opportunity is fusion. General Fusion, the fusion technology start-up in Burnaby, B.C., is urging the federal government to devote part of Chalk River’s mandate to fusion research.

“There is expertise at Chalk River, world leading in some cases, in areas such as tritium handling,” explained Michael Delage, vice-president of business development at General Fusion.

Tritium is a radioactive form of hydrogen, and is a byproduct of Candu reactor operation. It’s also one of two isotopes that can be most easily combined to create a nuclear fusion reaction. General Fusion needs tritium, and could seriously benefit from Chalk River’s tritium handling expertise.

Whitlock pointed out that Canada once had a fusion program at Chalk River. In fact, in 2001 Canada put in a bid to host the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project. But we never backed up ambition with money. The federal government cut funding to our fusion program in 1997, and a general lack of financial support led to our withdrawal in 2003 from the ITER consortium.

With Chalk River once again under the spotlight, it’s time to make some choices.

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.